Bhuvan—A brave new world or the same old?

One of the problems with the future is that it’s unknowable, but otherwise there are no issues. The other problem I have is with the news. If you read the news in 2025, it’s very hard to resist the feeling of ominousness. Even taking into account the negativity bias both in the media and our own brains, and their penchant for sensationalism, it doesn’t feel like we’re living in normal times.

Here are a few things that have happened in the last couple of weeks that stand out in my mind:

- The president of the United States insulted and berated Zelensky, the leader of war-torn Ukraine and an ally.

- The US flip-flopped on tariffs on Mexico and Canada for the second time in two months.

- In a historic move, Germany is loosening its fiscal straitjacket by exempting defence spending from its debt brake.

- Friedrich Merz, Germany’s chancellor-in-waiting, said something unimaginable a few months ago: “My absolute priority will be to strengthen Europe as quickly as possible so that, step by step, we can really achieve independence from the USA,”

- French President Emmanuel Macron floated a trial balloon of extending the French nuclear umbrella to other European countries. This comes after another historic moment where commentators in the FT labelled the US as an adversary.

- On the same page of the FT, Gillian Tett wrote that Trump is serious about radical proposals like devaluing the dollar and forcing countries holding treasuries to swap them for perpetual dollar bonds. This is in exchange for security and relief from tariffs.

- China is setting up a $138 billion VC fund to support tech startups while Trump finds ways to gut the IRA and CHIPS Act.

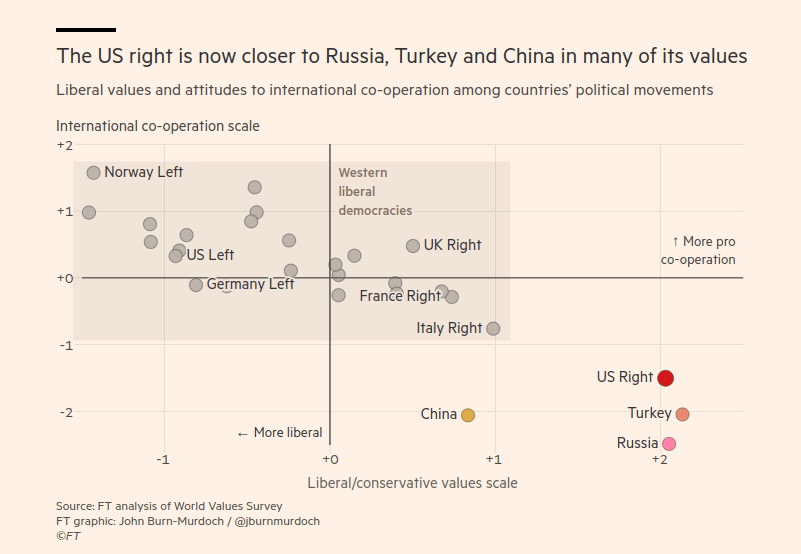

Then I saw this depressing graphic by the data wizard John Burn-Murdoch in the FT:

In the realm of geopolitics, it was unthinkable that the US would suddenly suspend military support from a longtime ally fighting off an invasion — until it happened. In economics, surely Trump and his team wouldn’t take action that could tank US stocks, let alone cause GDP to contract? Think again.

But the series of shock decisions — not just the rhetoric — from Trump, vice-president JD Vance and Elon Musk are less brain-bendingly inexplicable once you realise this: their version of America is operating on an entirely different set of values from the rest of the western world.

At the depths of the COVID crisis, I saw this Lenin quote on Twitter and it rings more true today:

"There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen"—Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

As you may have noticed from the last few posts, I’ve been searching for frames and heuristics to make sense of the world. I figured, why not ask ChatGPT as well? Here’s the prompt I gave:

We are living through a period of an insane amount of uncertainty. You have geopolitical crises, political instability, inflation, degradation of societal trust and norms, rise of AI and threats of mass unemployment, increased disillusionment among people and so on. Given that the world is so uncertain, what are some tools and heuristics that I should know to deal with uncertainty, make decisions and process them. I often hear people talking biases and the ability to hold two opposing ideas at the same time, but these trite remarks and observations strike me as unhelpful.

I then asked it to summarize the top 10 heuristics. I don’t know how useful they are, considering a lot of these are peddled by “mental model” bros, but I’m reading about them.

Pranav—What can $800 billion buy Europe?

Europe wants to re-arm itself, now that America’s breaking all its old promises. It has a “ReArm Europe Plan” in place, which intends to throw $800 billion at the problem over the next four years or so. That’s a scary large sum.

Perhaps its biggest challenge, as Andrew Korybko highlights, is simply the project it’s embracing. Now, I haven’t read much of him, but ChatGPT tells me that Korybko has a notable pro-Russia bias. Also, the Russian flag is literally superimposed atop his face in his display picture. Calibrate your pinches of salt accordingly.

His overall case, though, does make sense to me. At the heart of his case — at least to the extent I understand it — is that putting together an army with a common purpose, in a continent full of sovereign countries that have long, dark military histories, is challenging. The US, back when it gave a damn, did the job of giving direction and leadership to this grouping. With the US gone, it isn’t entirely clear where that might come from.

Korybko makes five arguments in his piece. I won’t go through all of them, but there are some larger things he’s hitting at. These are all generally a product of how these are all different nations. Even if they’re allied, each of them is bound to see their own interests as paramount, and superior to those of any other ally of theirs. This could play out in all sorts of ways. If asked “who ought to spend?”, they’ll all point at each other. But if asked “who ought to get contracts for military production?” they’ll all turn their hands around and point to themselves. They’ll probably eye each other with constant submission, and getting even simple things done will require considerable bureaucratic coordination.

My military history is rather weak, so I don’t know how much of a handicap this could be, if the proverbial shit were to ever hit the fan. How did large military alliances behave in the past? Were they able to put aside their differences and work together, when the danger was high enough?

The ancient Greeks are the only ones I know, and it seems like they had a bad habit of bickering all the time.

Krishna—Interesting statistics on greenhouse gas emissions

I got to know a couple of interesting stats on greenhouse emissions from this FT article.

- 36 fossil fuel and cement producers account for over half of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2023

- The top five state-owned emitters were responsible for nearly 20% of global emissions.

- Eight Chinese companies contributed 17% of global emissions, primarily due to continued coal expansion

- Emissions increased most significantly in Australia (11%), Asia (6%), and North America (3%), while Europe saw a 4% decline

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.