Bhuvan—How stories move economies

That economics has become too mathy and abstract is a tired trope. To say that economists have become enamored with elegant, complex mathematical models is almost clichéd. From Keynes to Hayek to Larry Summers, numerous economists have made variations of this argument.

There's some truth to it. All models are brilliant until they meet the reality of the world and the inordinately messy creatures that are human beings. Having said that, the criticism of "models" is also a little overdone. This is an argument that needs nuance, but unlike soundbites, nobody gives a shit about nuance.

Anyway, behavioral economics and finance was, in a way, an outgrowth and a reaction to the mathification of economics. Despite its flaws and problems, behavioral economics has been phenomenally helpful in improving our understanding of both economies as a whole and the individual atomic units within it—the messy and buggy humans.

One of the more useful contributions to behavioral economics in recent years was from the Nobel laureate. In 2019, he published a book called Narrative Economics, in which he argued that economists have long ignored the role of how stories affect the broader economy.

Of course, this wasn't a novel insight, and the impact of stories on consumer behavior, savings, investments, etc., was already present in the behavioral economics literature. Shiller's own work prior to the publication of the book contained some elements of narrative economics. Shiller's contribution in the book was, one, to popularize the notion that stories matter—given his stature and the volume of his megaphone—and two, to create a scaffolding for a narrative approach to economic thinking to build on.

I've yet to read the book, but I've read an older address he gave on the idea, and I've heard numerous talks. The key argument he makes is that ideas are like viruses, and just like viruses spread and mutate, so do stories.

He says that this insight isn't groundbreaking and that people in marketing, sociology, etc., have known this for a long time, but economics has been slow to catch on. Narratives, even simple narratives, are heuristics people use to make sense of the world, and their power is vastly underestimated. Studying the spread of narratives and their mutation can give us insights into economic events, asset price movements, consumer behavior, panics, and much more.

Shiller argues that, thanks to the vast corpus of digitized text that's now available, tracing narratives, their spread, and their mutation is easier than ever. Since the publication of his book, AI models have become widely available, and they've further made the task of digitizing old and arcane texts even easier. The other dimension of AI models is that they also contribute to the mutation of narratives, but that's a topic for another day.

As someone who works in a stock broking company and has a front-row seat to the madness that unfolds every day, this framing is bang on. People disagree, but we humans are storytelling creatures, and stories are how we make sense of the world and cope with the chaos and uncertainty of the world.

It's not a huge logical leap from accepting that humans are hardwired to think in stories to saying that those stories affect how people behave as economic actors and that those actions have real economic consequences.

The reason why I am talking about all this is because I read this new paper by Joel Flynn and Karthik Sastry, in which they analyze the impact of narratives on business cycles, and it makes for interesting reading. They find that narratives can explain a lot of economic developments. A few findings from the paper:

- Companies with more optimistic narratives tend to invest more and hire more. Surprisingly, the stock returns and profitability of companies with optimistic narratives aren't particularly high.

- Narratives are also contagious. Companies tend to adopt the narratives of their competitors, both at the industry level and the aggregate level. As an example, the entire "AI-powered" narrative comes to mind.

- If a narrative is sufficiently powerful—if it crosses a virality threshold—it can create self-sustaining cycles of economic optimism or pessimism. That is to say, a feedback loop between narrative sentiment and economic performance is created, one feeding on the other.

- Here are a few stats that stood out to me:

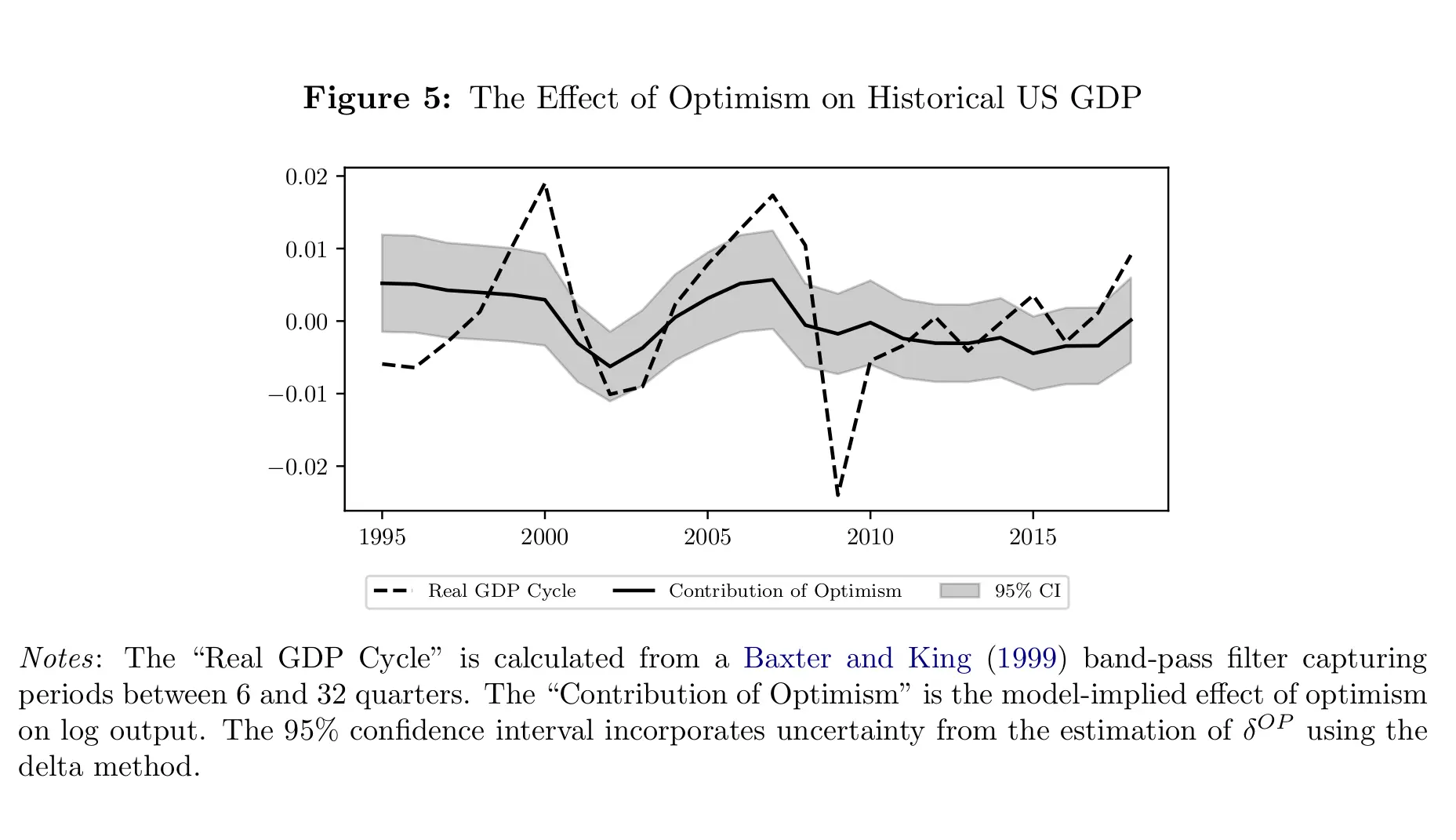

- "How strong are the narratives driving the US economy? Combining our empirical results with our theoretical model, we estimate that narratives explain about 20% of the US business cycle since 1995 (Figure 1). In particular, we estimate that narratives explain about 32% of the early 2000s recession and 18% of the Great Recession. This is consistent with the idea that contagious stories of technological optimism fueled the 1990s Dot-Com Bubble and mid-2000s Housing Bubble, while contagious stories of collapse and despair led to the corresponding crashes. Our analysis, building up from the microeconomic measurements of firms’ narratives and decisions, allows us to quantify these forces."*

First, what people say about their economic situation is highly informative about both individual attitudes and broader trends in the economy. Public regulatory filings and earnings calls already contain considerable information. Both policymakers and researchers can use improved machine-learning algorithms and data-processing tools to analyze this information. There are also possible implications for how researchers and governments collect information. The same data-science advancements have increased the value of novel surveys that allow households or businesses to explain the ‘why’ behind their attitudes and decisions (e.g. Wolfhart et al. 2021).

Second, some narratives are more influential and contagious than others. It is therefore important to combine descriptive studies measuring narratives with empirical analysis of their effects on decisions and their spread throughout populations.

From the main paper:

Our main results analytically characterize how narratives can generate non-fundamental fluctuations in aggregate output, hysteresis, and boom-bust cycles. We first establish that there is a unique equilibrium in which aggregate output is log-linear in aggregate productivity and a non-linear function of the fraction of optimists in the population. We refer to the latter effect as the non-fundamental component of aggregate output, because it is driven by the state of narratives rather than any fundamental change in productivity. We decompose this component into a partial-equilibrium effect of optimism on firm hiring as well as a general-equilibrium narrative multiplier driven by strategic complementarities: even if a firm is pessimistic, the presence of other, more optimistic firms causes them to produce more. The equilibrium effect of narratives is smaller if firms have access to more precise information, as this leads them to rely less on narratives to form their beliefs. However, because of the narrative multiplier, the power of the truth to stop false narratives is weakest exactly when narratives are strongest. Importantly, as equilibrium is unique, fluctuations in our model are not driven by sunspots or movements between multiple equilibria.

Charts

The Effect of Optimism on Historical US GDP

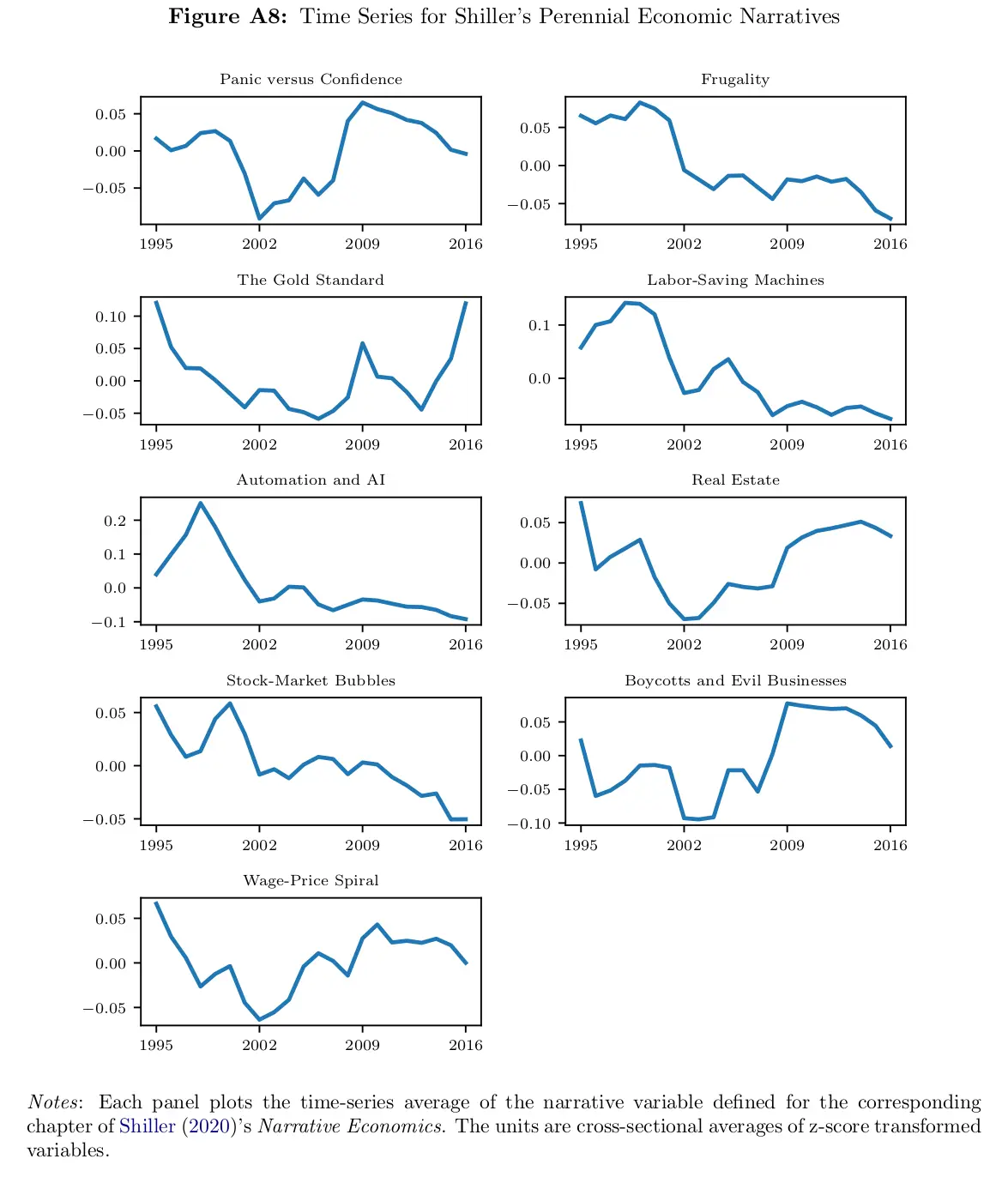

Time Series for Shiller’s Perennial Economic Narratives

Krishna—RBI is keeping the rupee stable

I came across the comments of the former CEA, Arvind Subramanian, where he’s saying *RBI followed a highly unfortunate exchange policy.* Here’s what he is saying:

The value of the rupee, like any currency, is fundamentally determined by supply and demand. When demand for the US dollar increases (which is common), its value rises relative to other currencies, causing the rupee to depreciate. According to Subramanian, since mid-2022, the RBI has been actively intervening in the foreign exchange market to maintain rupee stability. This intervention typically involves selling foreign exchange reserves to prevent the rupee from depreciating (when RBI sells dollars and buys rupees, it reduces rupee circulation in the market, supporting its value).

Subramanian argues that this policy of maintaining rupee stability could be detrimental to India's economy. One key concern is its impact on exports: when the rupee remains artificially stable while other emerging market currencies depreciate, Indian exports become relatively more expensive in global markets, potentially hurting their competitiveness.

I’ll cover more of this in this week’s Who said what?

Pranav—ompleting India’s economic reforms

Here’s my last post on Doug Irwin’s excellent paper on India’s liberalisation. It’s been a pleasure — a comprehensive expansion of how I thought and what I knew about that episode of Indian history.

First, here is how others perceived the reforms:

First, the bureaucrats.

When liberalisation was carried out, most bureaucrats were deeply sceptical. After all, they hadn’t been asked what they thought before such a major step.

To high-level bureaucrats, this was just an ego issue. The 3,000 low-level bureaucrats in the Chief Controller of Imports and Exports, however, saw their pockets being hit. After all, if they no longer sat on India’s 2 lakh annual import license applications, how would they earn bribes.

But MMS DGAF. He assembled the day’s top bureaucrats, and told them, “This is what needs to be done and the PM has given me full authority to get it done. If any one of you have any difficulty with this, speak up now and we can find you other things to do.” For a silent Prime Minister, he could fire some sharp words, huh?

Bureaucrats couldn’t say much in public, however. Not so for left-wing intellectuals. Prominent academics wrote open letters asking for liberalisation to be abandoned, instead pushing for a return to the old import repression regime.

There was also pressure from politicians, of course:

This was PV Narasimha Rao’s crowning achievement — to manage the Congress when it was railing against his changes. For three days, members of the party vented their anger in Parliament.

In 1992, he managed to win a vote within the party in favour of liberalisation, by convincing everyone that liberalisation was in line with what Nehru wanted.

Those outside the party, meanwhile, raised hell. The Left cried about how socialism had been abandoned, while the Right (including the Bhartiya Janata Party, funnily enough) complained about foreign influence.

Curiously, Vajpayee apparently told Manmohan Singh that it was the duty of the opposition to criticise and oppose, but he should disregard it and continue with the good work.

A common criticism against the government was that the government had bowed its head before the IMF. Of course, this is something that so many people still believe — including our dear Kasis. But the truth is that the negotiation with IMF was only opened in August 1991, after trade reforms had already been announced.

On July 15, the government faced a no-confidence motion. The opposition was divided, however. Rather than vote with the BJP, the left staged a walk-out. Their 112 votes turned into abstentions, and the government survived 241-111. Several no-confidence motions followed, and the government survived them all.

All the subsequent budgets, which furthered reform as well, went through Parliament.

Businesses were wary of the reforms, though they didn’t make much of a scene. Their mantra was that internal liberalisation should predate foreign liberalisation. Either way, they were broadly ambivalent — apart from a small club in Mumbai that had political patronage, that was wilting away.

Funnily, enough, it seems like most people didn’t understand the changes to trade policy, so there was remarkably little backlash. Labour unions, for instance, hated devaluation and the end of industrial licensing — but didn’t say anything about trade policy.

Ultimately, while there was opposition against the reform from many quarters, there was nobody who was really in favour of it. Except, of course, for a few technocrats.

Reality, of course, was the biggest constituency of the reforms. Ultimately, the successes were clear for all to see. Exports grew rapidly. Forex reserves expanded. “Successes made new believers of old sceptics.” The government had a smoother part afterwards.

What came after liberalisation:

A key goal, following liberalisation, was to unify the exchange rate:

In 1992, a weird system had been created — where businesses could retain 60% of their foreign exchange, which would be valued at market rates, while the remainder would be submitted to the government at the official exchange rate. The idea was that these two rates would progressively move closer, until the official rate could be done away with.

This was accomplished in 1993, and in 1994, the Rupee was made fully convertible. This allowed us to finally ease our neurotic forex-obsessed licensing system. What’s more — finally, these measures were completely outside the political process, and didn’t draw any opposition whatsoever.

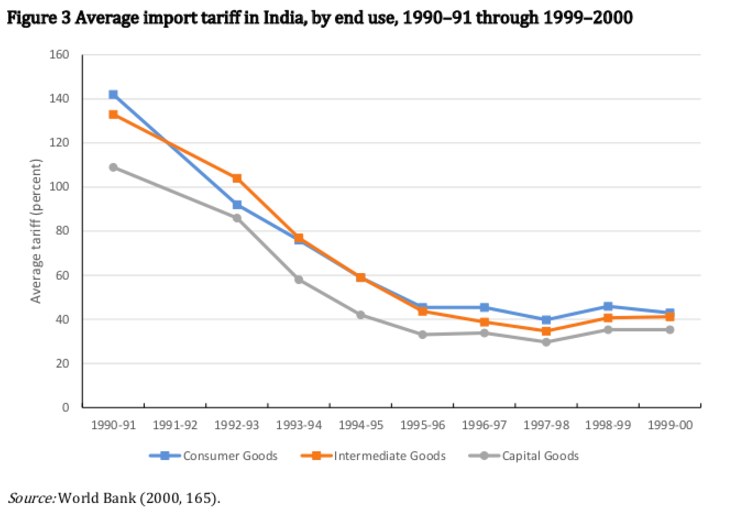

Another was to bring down tariffs — which averaged 90%:

In 1991, tariffs made for one-third of the revenues of the government. India therefore needed to change its revenue system entirely before duties could be lowered.

Tariffs were brought down budget-after-budget, until they came down to a 5-35% range. This came about without much domestic backlash - possibly because Indian exports had progressively become more attractive as the Rupee fell.

- This also took some regulatory engineering. The Finance Ministry realised that while the Parliament placed a maximum cap on tariffs, they could be brought below this floor without Parliamentary sanction. Accordingly, the Ministry basically cut tariffs down by stealth.

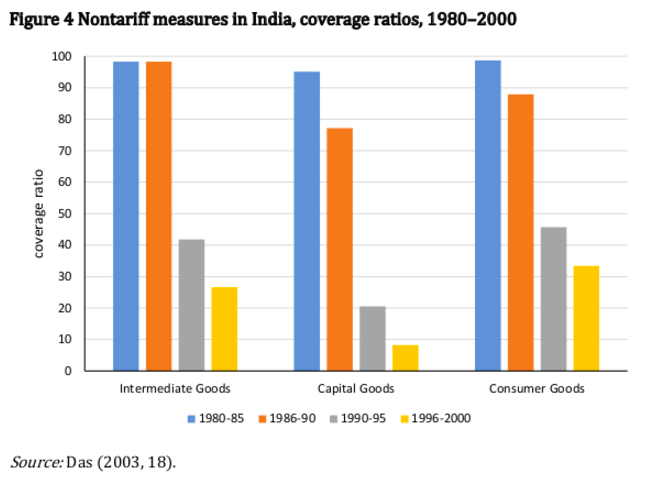

Finally, the government brought down quantitative restrictions on imports.

In 1988-89, 95% of our imports were covered by non-tariff barriers. That is, we didn't just tax their import, we put quotas and legal barriers on their import. By 1996, this was at 36%.

Eventually, all these barriers were unravelled, as government monopolies were removed in a variety of sectors - petroleum, medicine, cereals and consumer goods.

Anurag—How does climate change affect AQI?

I have lately been reading up a lot on AQI, and something I was curious about today is how climate change affects AQI in details beyond the obvious. What I discovered was fascinating – there's an intricate web of connections between our changing climate and the air we breathe, particularly in places like India where these effects are becoming increasingly visible.

Disclaimer: While I’ve tried to refer to credible sources as much as possible, I’m not an expert, so I can’t guarantee that everything here is factually and biologically accurate. Still, I found some interesting points worth sharing.

Let's start with something that might surprise you - climate change is actually changing the way air moves above our cities. Think of the atmosphere as a dynamic system of moving air currents. These currents typically help disperse pollutants, much like stirring a cup of coffee helps dissolve sugar evenly throughout. However, climate change is disrupting these natural patterns, leading to more frequent episodes of stagnant air, especially in Indian cities.

In Delhi, for instance, during winter months, something remarkable happens in the atmosphere. The air forms distinct layers based on temperature – imagine it like a layer cake – where colder air gets trapped near the ground beneath warmer air above. Scientists call this a "temperature inversion," and it acts like an invisible lid, trapping pollutants close to where we breathe. As our climate continues to warm, these inversions are becoming more common and lasting longer, making each pollution episode more severe than it would have been otherwise.

But there's more to this story than just still air. Rising temperatures are actually accelerating chemical reactions in the atmosphere. When the air gets warmer, it's like turning up the heat in a chemical laboratory – reactions happen faster. This is particularly important for something called ground-level ozone, a harmful pollutant that forms when sunlight triggers reactions between other pollutants. As Indian cities experience more frequent and intense heatwaves, these chemical reactions are speeding up, creating higher levels of ozone that can irritate our lungs and worsen respiratory diseases.

The changing monsoon patterns add another layer to this complex story. Traditionally, India's monsoon rains have acted as a natural air purification system. Rain droplets capture pollutants and bring them down to the ground – nature's way of cleaning the air. But climate change is disrupting this ancient pattern. Instead of regular, predictable rainfall, many regions are now experiencing longer dry spells punctuated by intense bursts of rain. During these extended dry periods, pollutants accumulate in the air with no natural mechanism to wash them away.

Perhaps one of the most visible manifestations of this climate-pollution connection is the increase in dust storms. As climate change makes some regions hotter and drier, the Thar Desert is expanding its reach. This desertification creates more frequent and intense dust storms that carry fine particles across vast distances. These aren't just ordinary dust particles – they're small enough to penetrate deep into our lungs and even enter our bloodstream. Cities like Delhi, Jaipur, and Ahmedabad are experiencing more of these storms, adding natural pollutants to their already challenging air quality situations.

What makes this situation particularly challenging is that it creates a feedback loop. The pollutants we release into the air don't just affect our health – many of them also contribute to further climate change. Black carbon, for instance, which comes from diesel vehicles and coal plants, both harms our lungs and warms our atmosphere. When it settles on Himalayan glaciers, it makes them absorb more sunlight and melt faster, affecting water resources for millions of people.

Looking ahead, scientists predict that by 2050, even if we keep emissions at current levels, climate change will make air quality worse simply because weather patterns will become less favourable for dispersing pollutants. This means that solving India's air quality challenges requires addressing both local pollution sources and global climate change simultaneously.

Tharun—Microplastics: From your balls to your brains

Microplastics are those microscopic plastic particles smaller than 5 millimetres that have sneaked their way into pretty much everything around us. And when I say everything, I mean everything - including our bodies.

For years, scientists have been finding microplastics in various human organs - from our blood to our lungs. Last year, researchers found microplastics in human testicles. And they think this might be why sperm counts in men have been reducing globally.

And just when we thought our brains were last plastic-free, researchers dropped a new study last week.

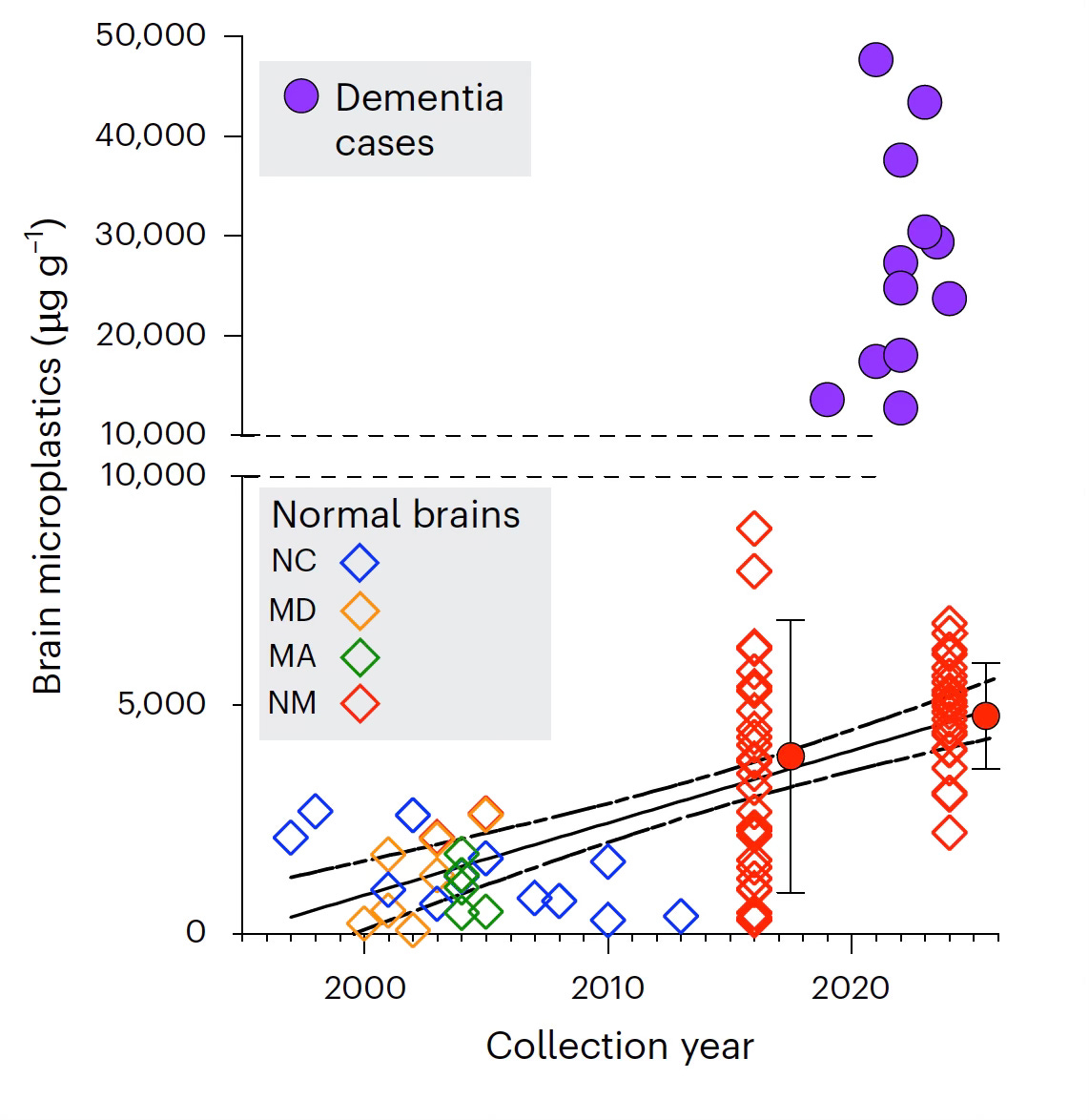

Here are some findings that might keep you up at night:

Your brain could be hosting 7 to 30 times more microplastics than your liver or kidneys People struggling with dementia showed 2 to 10 times higher microplastic levels in their brains compared to those without the condition

Since 2016, we've seen almost a 50% jump in the amount of microplastics found in human brains So now climate activists fighting plastic are most likely telling the truth when they say the only thing they have in their minds is plastic.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.