Bhuvan—getting smarter with dumb chat bots

The philosopher George Santayana once didn’t exactly say:

Those who forget their history are condemned to repeat it.

Regardless of how you’re interested in finance, a decent understanding of history is indispensable. I don’t know if history makes you smarter, better, or helps you make better decisions, but at the very least, it teaches you that there’s very little that’s truly new under the sun.

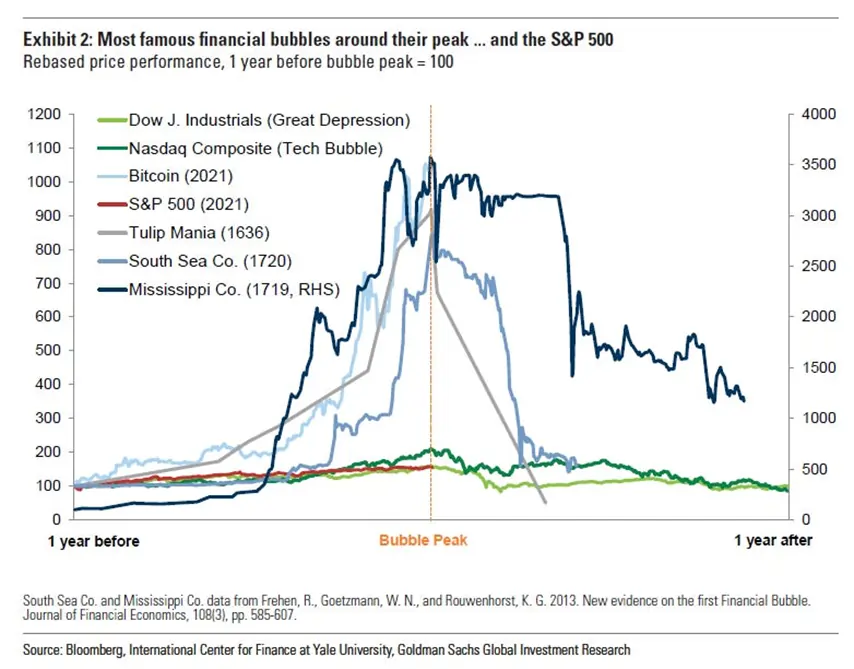

I’m fascinated by financial crashes and bubbles. One of my enduring obsessions has been the 2008 global financial crisis—it probably did more to spark my interest in finance and economics than anything else. If you were to rank the biggest market bubbles in history, another that would undoubtedly make the top 10 list is the Japanese stock market and real estate bubble of the 1990s.

Apart from knowing that the Nikkei 225 index peaked in 1989 and took 34 years to reclaim that peak, I knew almost nothing about the bubble. Oh, I forgot one thing: I remember reading that at the peak of the real estate bubble, the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was supposedly worth more than all the land in California. The Japanese property market was estimated to be worth about four times more than the U.S. property market, despite Japan occupying only about 4% of America's land area. Talk about crazy!

Anyway, I was reading this article on Japan's stagnation when I got the bright idea of asking AI tools to help me learn about the Japanese asset price bubble. Despite being a regular user of AI tools like ChatGPT and Claude, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality.

A few weeks ago, I told a colleague in passing that, thanks to these AI tools, we no longer have an excuse to be ignorant about anything—and now I’m convinced. These tools are like having someone who knows a fair amount about everything in your pocket. I think most people are still stuck in the “these are dumb chatbots that hallucinate and say wrong things confidently” frame of mind.

To be honest, that’s how I felt when ChatGPT became mainstream. But after playing around with these tools for a long time, I can say with confidence that I was wrong. These tools have gotten ridiculously good, and their utility has increased significantly in the last year or so.

No matter what your priors are, being dogmatic that “they’re bad” without experimenting is the wrong frame of thinking. This isn’t to say that these tools are a shortcut for reading, thinking, and writing.

No.

They reduce the barriers to knowing a little about a lot of things. That said, if you want to know a lot about something, they’re more than capable.

So, I asked ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini this:

Why did Japan stagnate from the 90s? What does the economic literature say? Include a diverse range of opinions from all sides of the economic and ideological spectrum.

Tell me about the run-up to the bubble. How did the bubble form, how did it pop, what was the international context, how did policymakers react, and more.

Here’s the TL;DR as I’ve understood it from these large language models (LLMs):

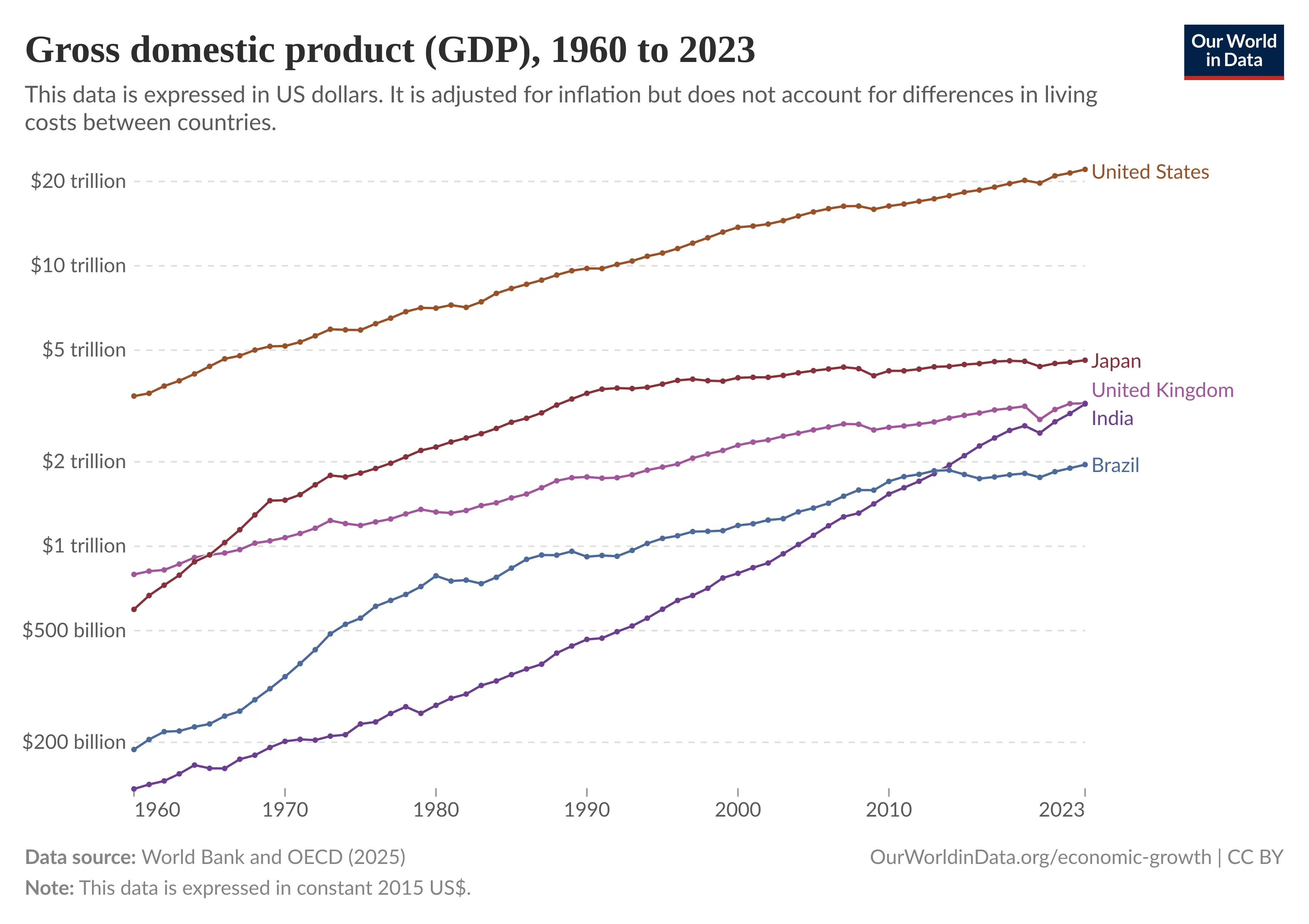

After World War II, Japan grew spectacularly, experiencing a period of rapid catch-up growth. By the 1980s, it had become the world’s second-largest economy after the United States.

Factors like strong industry-government cooperation, export-led growth, and high domestic savings were key to this rapid growth. However, by the mid-1980s, the U.S. was running large trade deficits due to a flood of Japanese exports, and U.S. manufacturers were struggling against the onslaught.

In 1985, the U.S., Japan, West Germany, France, and the U.K. signed the Plaza Accord, agreeing to devalue their currencies against the yen to make U.S. exports more competitive. As a result, the yen appreciated dramatically, threatening Japanese exports.

To protect the domestic economy, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) cut rates from 5% in 1985 to 2.5% in 1987. This led to an expansion of cheap credit, fueling unprecedented speculation in the stock market and real estate. Thanks to regulatory changes, even companies started borrowing money to speculate in stocks, reportedly making more from trading than their core business.

By the late 1980s, real estate and stocks had reached unprecedented highs. All good things must come to an end: In 1991, the bubble popped. Asset prices collapsed, banks were saddled with massive bad loans, and household balance sheets were severely underwater.

Starting in the 1990s, Japan entered its lost decades—a period marked by low growth and deflationary pressures.

What caused the bubble?

Decades later, there’s still no consensus on why the bubble formed and why it popped. Commonly cited reasons include:

- The Plaza Accord (1985): BOJ’s aggressive rate cuts made money cheap and speculation easy.

- Deregulation: In the 1980s, Japan’s financial deregulation enabled banks and companies to take excessive risks.

- Speculative Beliefs: The belief that land prices would always go up fueled real estate mania.

- Financial Engineering: Companies speculated in stocks outside their core business.

- FOMO and Feedback Loops: Rising asset prices fueled a virtuous cycle of greed and speculation.

Why did Japan stagnate when other countries recovered from their bubbles?

- Balance Sheet Recession: After the bubble burst, households and companies prioritized paying down debt. Despite low interest rates, nobody was borrowing, creating a liquidity trap.

- Weak Fiscal Policy: Japan’s fiscal response was slow and inadequate.

- Demographics: A rapidly aging population reduced productivity and economic growth.

- Zombie Companies: Banks kept lending to insolvent companies, stifling innovation and productivity.

- Policy Missteps: The BOJ hesitated to cut rates aggressively or embrace quantitative easing (QE) fully.

- Rigid Corporate Structures: Close industry-government ties slowed reforms.

- Overregulation: Labor market rigidities and excessive government intervention worsened stagnation.

AI as a Research Companion, Not a Replacement

I learned all this from ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini. But if I stopped there, my understanding would be surface-level at best. Many people make this mistake—stopping their search and taking AI outputs as gospel. I think that’s the wrong way to use these tools.

You should use LLMs to get a solid grounding but then dig deeper.

So, I started Googling for widely cited papers on the Japanese crash and came across this thought-provoking paper by Adam Posen of the Peterson Institute. It debunks many of the common claims I learned from the AI tools:

- Loose monetary policy wasn’t the cause: Asset prices were already rising before BOJ cut rates. Even early rate hikes wouldn’t have stopped the mania.

- The crash was worsened by policy failures: Delayed rate cuts, tax hikes in the late 1990s, and a failure to regulate banks made the downturn worse.

- Liberalization, not low rates, fueled speculation: The liberalization of capital markets pushed companies to borrow from markets instead of banks. To replace lost business, banks made risky loans to small firms and real estate ventures, fueling the bubble.

- It wasn’t just about cheap money: Rising collateral values and looser lending standards set the stage for the bubble, independent of low interest rates.

A More Nuanced Understanding

Reading Posen’s paper gave me a more nuanced understanding of Japan’s crash. It also opened up new rabbit holes to explore. That’s what makes these LLMs fantastic companions—they can help you understand the surface area of a topic and give you a solid grounding. But they’re best used alongside other sources. I never let them be my only source of learning.

That approach has helped me learn a whole lot of new things that I otherwise wouldn’t have.

Krishna—Trade prices

I was reading up on the cement sector, and I came across these 2 terms: trade prices and non-trade prices. Here’s what they mean:

Trade Prices:

- These refer to the prices at which cement companies sell to the retail segment—individual consumers, small contractors, and local builders.

- Because of the smaller volumes and higher bargaining power of the seller, cement companies can maintain higher prices and enjoy better margins.

Non-Trade Prices:

- These apply to bulk purchases by government entities or large infrastructure companies.

- Prices here tend to be lower than trade prices, which results in slimmer profit margins for the cement companies.

Kashish—It’s time to go from low user agency to high user agency

I was reading an Inside post (an internal Reddit of sorts for Zerodha employees) by our CTO. Most of the time, what he shares is Greek and Latin to me, but when someone of that stature and knowledge shares something, you’re better off not being critical and just bite the bullet.

He had shared a lot of links, but one of them felt interesting, so I clicked on it. It had something to do with how consumer app businesses should go about approaching decisions regarding feature launches. While discussing that could be a post in itself, I wanted to quickly write this post about another thing I found interesting.

Nearly all popular consumer software has been trending towards minimal user agency, infinitely scrolling feeds, and garbage content. Even that crown jewel of the Internet, Google Search itself, has decayed to the point of being unusable for complicated queries.

“Minimal user agency.”

This phrase stood out to me. I ChatGPTed it. This is what came up:

User agency refers to the level of control, choice, and influence a user has over their experience while using software, platforms, or digital products.

In the context of the sentence you shared, "minimal user agency" means that users have less control over what they see, how they interact with content, and how they navigate the platform. Instead of actively deciding what to engage with, they are passively fed content through algorithms, infinite scrolling, and recommendation engines.

Honestly, I agree with this. I know I haven’t been using consumer apps for that long—I only started interacting with tech and the internet after 2018, when I got my first device. So I don’t really know how the internet evolved before that, but I can still sense the direction it has been heading lately.

Low User Agency.

Basically, you have no control over what you get. As someone who earns a living as a knowledge worker, I spend most of my days on these platforms and apps because they’re a source of information for my work output. But sadly, all these platforms give me little to no control over what I consume: Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube.

Their algorithms may have been “optimized” for my preferences, but I never feel satisfied with what they feed me. It’s so frustrating to try and “train” and “feed” the algorithm what I want, yet it still gives me what it “thinks” I want.

I mean, I may not be a power user of all these apps, and maybe I’m simply struggling with using them effectively, but I know for a fact that I could be served better than I currently am.

What’s even more frustrating is that, since there is minimal user agency and the algorithm is calling the shots, what I’m served and what my friend is served is more or less the same. For two different personalities, being offered the same things is an insult to our unique identities. But to algorithms, there aren’t “unique identities,” just “buckets of similar accounts” of early-20-something single male users.

My disgust with this knows no bounds. No doubt, when my boss introduced me to the world of RSS feeds, I was shocked. I could not imagine such a technology existing where I would only be served what I want—truly the highest user agency. Surprisingly, since the code for RSS feeds is stuck in time, it’s actually a good thing, because now I get exactly what I want.

Pranav—Does management matter?

A good friend recently sent me a very interesting piece on tariffs by Nicholas Decker. While I've been reading about tariffs for a while, now, there was quite a bit in here that I had no idea about. Here are some quick notes on the things that blew my mind:

Why are businesses in our part of the world so terribly inefficient? A big answer, it seems, is the poor quality of our management. Repeated studies show that getting some basic SOPs in place can transform a business completely --- with double digit changes in productivity. It's a no-brainer. For instance, researchers in Mumbai got management consultants to help textile businesses improve how they went about things. Every $1 spent on these improvements created more than $81 in profits. I know people love hating on the McKenzies of the world, but they clearly bring something to the table.

There's more to this. The difference between the developed world and a country like ours isn't really about how the best businesses work. Good businesses, like happy families, are similar all across the world. Most of the difference, though, lies in our long tail of extremely unproductive businesses.

Because of our exceptionally poor court system, it's much harder to trust outsiders --- in case someone screws you over, there's absolutely nothing you can do. This is one reason India has so many family-run firms. In fact, the size of Indian firms is strongly correlated with the number of male family members.

It's actually really hard to make a business improve. Most people don't do things that are obviously better for them, simply because they don't feel like they need it. Competition, though, pushes businesses to change --- and change remarkably fast.

To put this together, competition creates better managements, and better managements make better businesses.

Modern economics actually disproves Ricardo --- but in a rather unintuitive way. Comparative advantage does not, it turns out, work in a way where different countries learn to dominate different industries. Instead, when several markets are stitched together, what you see actually is a numbers of thriving businesses from different countries, all selling across borders. To a consumer, this translates into a wide variety of goods. And as anyone that's been wowed by a well-stocked supermarket (or quick commerce app, for that matter) can attest, consumers love choice.

All successful countries do some sort of industrial policy. All unsuccessful countries do some sort of industrial policy. If you're debating if a country should do industrial policy, you're an idiot. You should ask what industrial policy one should do. What you want to aim for is 'learning by doing'. You want to make your businesses make more stuff, as long as doing so teaches them something --- something which will cut their costs down in the future. If you can't do that --- or if someone else does it better --- you simply don't do industrial policy.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.