Bhuvan

Ever since we started the Markets by Zerodha YouTube channel, my longstanding fascination with China was rekindled. In fact, I even recorded a terrible video on the topic. To my colleagues who write here, this fascination seems like an obsession and has made me the butt of repeated jokes—mostly lame ones. But even if you just spend a few hours reading about the Chinese economy, you'll quickly get a sense of just how important it is to the global economy. To make this rather simple statement more concrete, I'd suggest a simple experiment: try going through a day without using a Chinese product.

The reason I bring this up is because there was an interesting article in the Financial Times about how China might soon be hitting "peak oil." This is a topic I've closely followed, and some of the shifts in China regarding its oil consumption are stunning, to say the least.

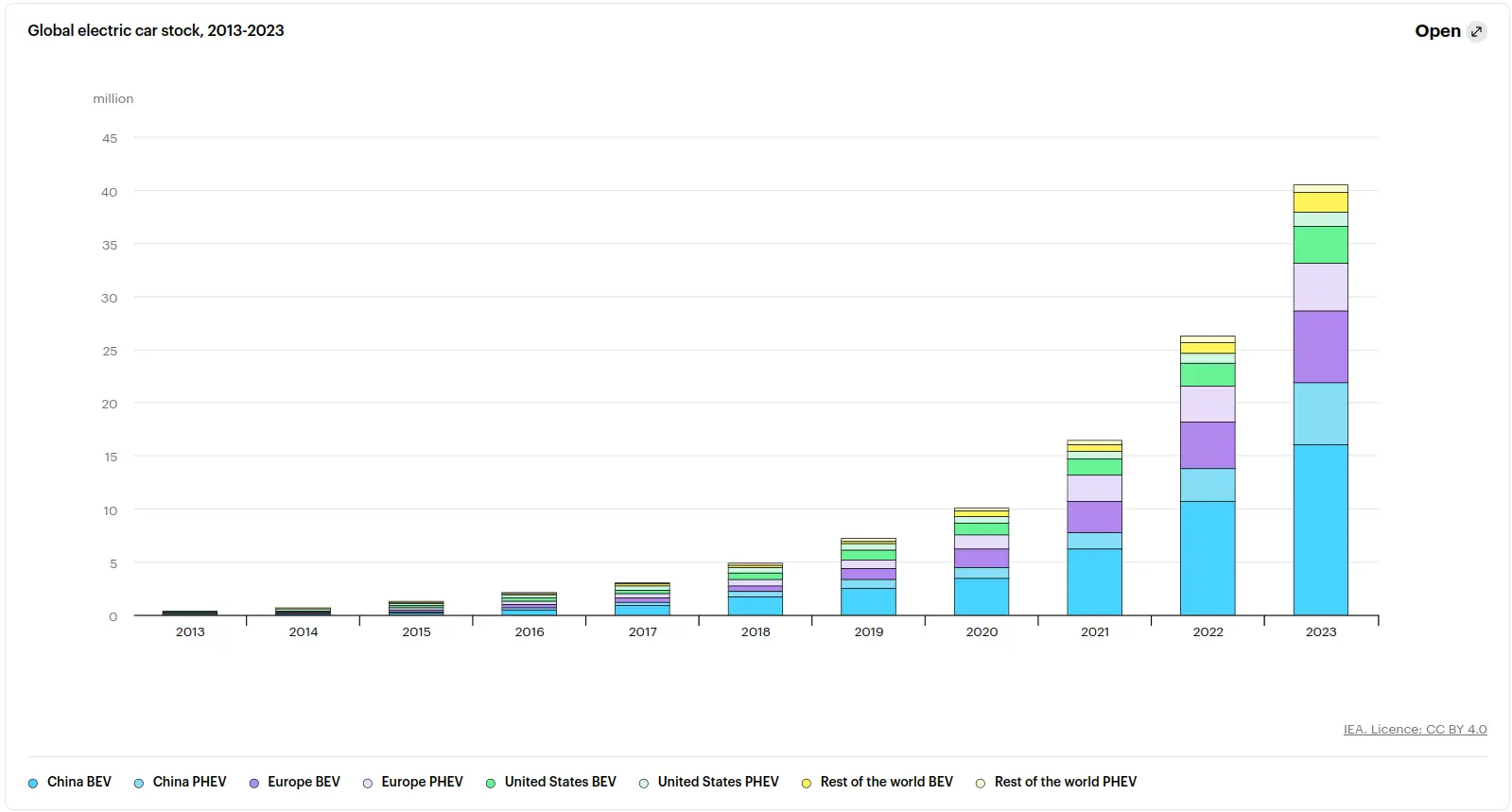

In the first few weeks of 2025, Chinese oil demand saw its first decline in two decades. The obvious suspect behind this decline is, of course, the terrible Chinese economy, but that's not the only reason. There are fascinating shifts in its transportation sector that may be reducing its demand for oil. The first big shift is the rise of electric vehicles (EVs).

According to the IEA, about 60% of all EVs sold worldwide were in China. It further projects that 75% of all Chinese car sales will be electric by 2030.

Source: IEA

The second major shift reducing demand for diesel—apart from the construction slowdown—is the transition toward LNG trucks. A statistic I saw on the blog of Kpler, a trade intelligence firm, puts this into perspective. They predict Chinese gasoline demand to slow to 2.6% between 2021–2030, compared to a counterfactual growth of 3.1% without EVs.

That said, it remains to be seen how much greenification and electrification of transport will actually reduce oil demand. The irony of the green transition is that you still need a lot of plastic—which comes from crude oil—to go green. Here's a telling quote from the article:

"For 5 megawatts of wind-generated power, you need 50 tonnes of plastics. For every electric vehicle, you need 200–230 kg of plastic. Even in solar panels, 10% comes from fiber, and so on. So for the transition to happen, you need more oil," he said.

But peak oil is not without its detractors. Last year, I listened to a fascinating podcast featuring oil expert Anas Alhajji, who seemed to dispel the myth of EVs significantly reducing oil demand. A few highlights from the conversation:

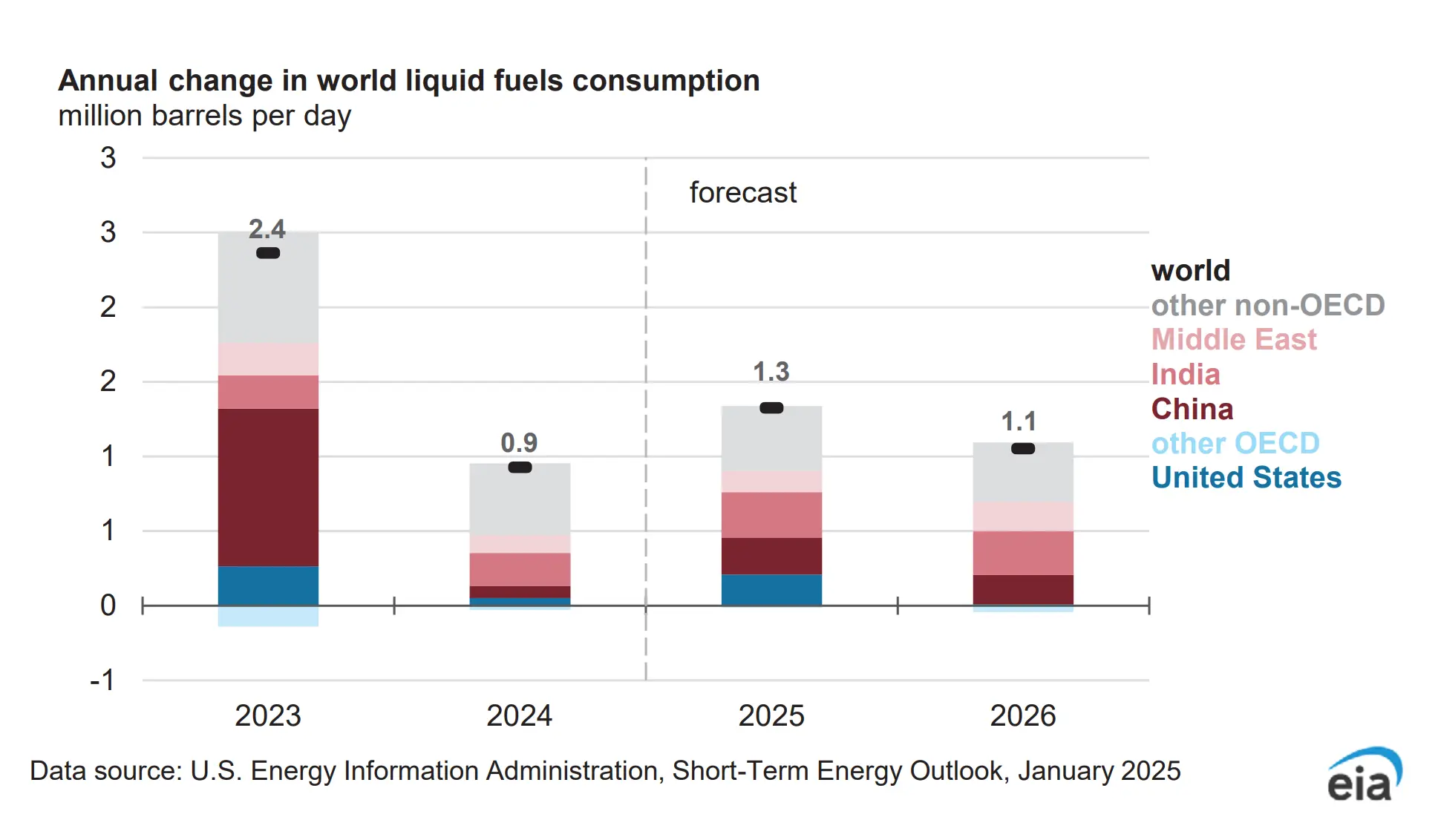

- There are only about 50 million EVs in the world, and they've only reduced oil demand by about 1.2 million barrels a day. For context, the world consumes over 100 million barrels of oil daily.

- EV production in China has increased the demand for crude derivatives like LPG and naphtha.

- Heavy EVs experience faster wear and tear on tires, which paradoxically increases demand for crude-based products.

- A large portion of the decline in Chinese oil demand is due to slow economic growth, not the adoption of LNG trucks and EVs.

Source: EIA

Krishna

eToro, a UK-based company, is planning to list on the New York Stock Exchange. This adds to a growing trend of companies moving away from the London Stock Exchange (LSE). Since 2020, companies accounting for about 14% of the total value of the FTSE have left the London exchange for listings overseas. Why is this happening? It largely comes down to the appeal of a larger pool of investors and the potential for better liquidity in their shares.

One more thing: Lighters were invented before matches!

Kashish

Reliance has an oil business, but it’s divided into two parts: upstream (E&P) and downstream (O2C). These are just fancy terms for different stages in the energy value chain.

When crude oil and natural gas are first produced, it’s called the upstream or exploration and production (E&P) business. Revenue here depends on crude oil and natural gas prices, production volumes, and exploration success. Profits can be quite volatile due to fluctuations in global oil and gas prices. This part of the value chain is positioned at the very beginning and provides raw materials like crude oil and natural gas to refineries and other users.

But crude oil in its raw form is not useful—it needs to be processed and refined for practical purposes, like vehicle fuel or chemical production.

That’s where the downstream or oil-to-chemicals (O2C) business comes in. This part focuses on refining crude oil and natural gas into products like fuels, plastics, and chemicals. It converts raw materials into high-value end products like petrol, diesel, polymers, polyester, and aromatics. Revenue for this segment comes from selling these refined products.

Now, the obvious question that came to my mind was: Does E&P output get fully absorbed by the O2C business? It’s a fascinating setup where one business’s output becomes another’s input, potentially boosting the company’s overall margins. After some digging, I found that this is mostly the case.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what percentage of E&P output is absorbed by the Jamnagar refinery and what percentage is sold externally, but it’s safe to say that most of the crude is consumed internally. However, Reliance also evaluates the economic returns of selling E&P output externally versus using it within the O2C segment.

Looking ahead, things might change. Reliance is moving into new energy businesses, and its focus on renewable energy and low-carbon solutions might lead to shifts in how its E&P output is utilized. I still need to dig deeper into this, so I’ll leave this thought unfinished for now.

Source: Reliance Investor Presentation, ChatGPT & Claude.

Pranav

Today, I’m going to basically plug a conspiracy theory. Sorry. But this conspiracy theory taught me a whole lot of interesting, important stuff about the AI industry. And if any of it is actually true, we’re staring at a fundamental change in the industry’s economics.

My disclaimer: I’m not an engineer. I don’t understand computers, and I certainly do not understand AI. I mean, I have no sense of it at all—I'm like a deaf person commenting on how Mozart is more mellifluous than Beethoven.

Anyway. Last night, Alberto Romero published a banger of a Substack post with an entirely speculative claim: that OpenAI already has GPT-5 in place - it just isn't releasing it to the public. And that’s really interesting.

Why? Let’s start at the top.

See, a lot of our fancy LLMs are basically a giant collection of ‘transformers’. When you give an AI model something to read, a transformer helps it (in a very basic, computeristic sense) understand it. I don’t completely know how, but you could try out this excellent primer.

A new model is like a baby’s brain. It doesn’t know shit. But once you make a model basically read everything ever written, it starts forming all sorts of connections. Over time, the AI develops a fairly sophisticated sense of the world. This understanding gets better as you add more transformers to the mix. Ultimately, the formula’s simple: more transformers + more training = smarter AI.

For a while, companies did this linearly. With every model, they kept adding transformers and feeding even more data, and the model seemed to get better. Each model they released was bigger and more well read (so to speak) than the last. GPT-3, for instance, had 170 billion-odd parameters (transformers basically work with a collection of these parameters). GPT-4 had 170 trillion. It seemed like the AI companies were in an arms race to add as many transformers as they could.

But this was obviously madness. The complexity of AI was going up exponentially every year, and with that, each model was becoming exponentially more expensive. If you were offering these models to millions of customers, you’d burn through an insane amount of cash.

All this while, though, AI companies had figured something else—distilledation. See, when you first feed real-world data to an AI model, its ‘understanding’ is woozy and filled with noise. But you can take the best of what it has learned and train a smaller model for just that high-quality stuff. This smaller model almost becomes as 'smart’ as the big one, while staying niftier and cheaper.

Over the last year, the transformers arms race seems to have flagged. There have been a whole lot of recent reports on AI hitting a ceiling. Making models bigger still makes them better, but the improvement isn’t enough. The resources newer models require have shot up hugely, but the performance has only risen a little. Imagine a car company coming out with a new car model that’s 10 kmph faster than the old variant but guzzles ten times as much fuel. Would it make any sense? That’s the wall the AI companies ran into. Online rumours suggest that the next generation of flagship models—like OpenAI’s GPT-5, or Anthropic’s Clause Opus 3.5—are being scrapped.

It’s certainly true that they’re way behind schedule if they plan to release those models at all.

But have they been scrapped? Romero thinks that they haven’t. They’re just being run in secret.

Why? See, there’s little purpose in giving customers access to the newer models. The user experience isn’t going to be much better, but it’ll cost these companies a lot more. But the things these new models have learnt can still be useful—if you just distill them. If Romero is right, the frontier models are all now being held in secret. They’re purely being used as ‘teacher’ models, and it’s their 'students’ that we’ll get to interact with.

What does this mean for us, if true?

One, the AI industry—after burning through billions in investor money—has turned its focus to efficiency and costs. The era of ‘bigger is better’ is over. Expect companies to become thriftier, deploying small, purpose-fit models for their customers.

Two, the era where you and I had easy access to state-of-the-art tech is over. AI companies will keep their best models hidden, and we’ll only get to see facets of that level of intelligence, distilled into less powerful imitations.

Three, the industry’s business models will get more complex. A lot of how your products look will depend on the quality and nuances of a confidential model you’re keeping as a trade secret. The best work of the AI companies will all be hidden from their rivals.

Four, AI innovation is just getting started. Until now, we were just playing with the limits of transformers—seeing what happened if we stacked as many of them as we could possibly muster. Slowly, though, we’ll start exploring how we can refine and optimise the way we use them. Constraints breed creativity, and we might see some of that creativity play out this year.

I should caution you, though: some of Romero’s arguments are rather flimsy—speculating heavily on AGI and OpenAI’s contractual terms with Microsoft. That sounds more conspiracy-like to me, and frankly, I’m not very interested. But even the basics—the changing economics of the AI industry—are enough to keep me hooked. I look forward to developing this idea further.

Tharun

Ozempic/Mounjaro or GLP-1. You have probably heard of these terms. If you haven't, please send me your address because I want to live under the same rock. Headlines about people losing 20% of their body weight after starting GLP-1 drugs and the possibility of these medications addressing obesity and even Alzheimer's completely fascinated me. So much so that I went down the rabbit hole and we made an entire video on the origins and economics of these drugs on the Daily Brief Podcast, which you can find here.

Fun fact: The development of GLP-1 drugs was inspired by a hormone found in the saliva of a Gila monster

Later, I came across this article from The New York Times, which had some fascinating bits. Quoting directly from the article:

Patients on GLP-1 drugs have reported losing interest in ultraprocessed foods... Some users realize that many packaged snacks they once loved now taste repugnant. 'Wegovy destroyed my taste buds,' a Redditor wrote on a support group, adding: 'And I love it.'" The Return to Natural Flavors.

Almost everyone's cravings for ultraprocessed foods had been replaced with a lust for fresh and unpackaged alternatives. A 32-year-old scientist... said, 'Celery tastes like celery. And carrot tastes like carrot. Strawberry tastes like strawberry.' Since taking Wegovy, she added, 'I just started to realize that they taste wonderful by themselves.

This made me wonder why people on GLP-1 drugs prefer whole foods and fruits. After listening to this podcast from Vox, where Samhita Mukhopadhyay shared her experience with Ozempic, I think I can make sense of why this is the case.

Processed foods often lack fiber, are calorie dense, and contain ingredients like trans fats and excessive sugars, which can worsen digestive discomfort—something worsened by GLP-1 drugs, which slow digestion. Which is why, today, I learnt that some doctors prescribe laxatives along with GLP-1 drugs to manage side effects like constipation.

On the other hand, whole foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains naturally aid digestion. Their fiber content promotes regular bowel movements and supports gut health. Samhita's preference for whole foods, like grapes, makes perfect sense given their ease on the stomach.

But on the flip side, there's something intriguing brewing in the processed food industry. These companies are actively working on tweaking flavours and textures to overcome the reduced desire for processed foods induced by GLP-1 drugs.

Quoting from the same NY Times article:

In a glass-walled conference room, Mattson scientists prepared for me some of its foods tailored to GLP-1 users that are currently being conceptualized. Amanda Sinrod, a senior food scientist in a white lab coat, placed a plate of soft brown cubes on the table. She explained that she had enriched each NourishFit brownie bite with two grams of protein, for maintaining lean muscle mass during rapid weight loss. A peanut-butter swirl would push that protein level even higher. Protein can have a grainy texture and chalky off notes, but the NourishFits were defectless, smooth, and sweet with remote echoes of cocoa. Approximately one-third sugar and about 15 percent fat, the bite-size portions were 'self-limiting,' Sinrod said. Servings could be packaged individually.

How this industry evolves will be super exciting to see. I'll be diving deeper into this rabbit hole and sharing such fun info when I come across it.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.