Bhuvan—Jaane kya hoga Rama re jaane kya hoga maula re

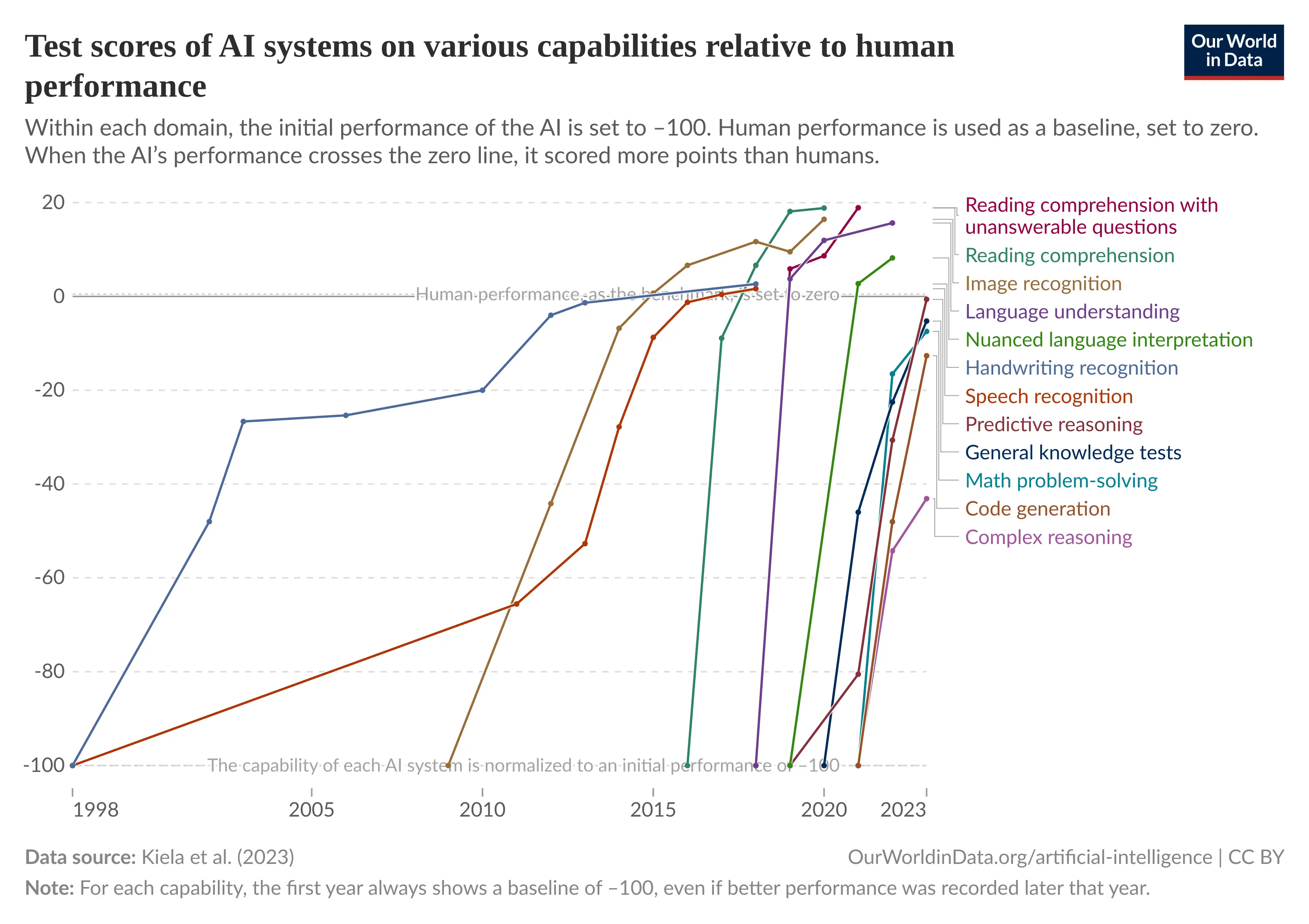

Whether you are an artificial intelligence boomer or a doomer, one thing you cannot deny is that these AI models—large language models (LLMs)—have become ridiculously good. I'll go further and say that, if we are honest with ourselves, we must admit these models are much better than we are at many things we think we’re good at.

[Test Scores of AI Capabilities]

One can, of course, argue that these are just dumb chatbots, and there’s something to be said for human judgment, experience, thinking, and essence, but that’s a different argument altogether.

My own heuristic for thinking about AI has been “disruption by default.” I start with the fundamental assumption that if AI continues to progress at its current rate—we don’t know if this is an eventuality or an impossibility—there will be wholesale disruption of society. It goes without saying that there’s no hard data to back up my view, but I have a strong vibe about this. I’m, of course, just linearly extrapolating the current rate of progress into the future. It might be dumb and naive, but that’s my view.

Nobody knows the future, but if I were to bet, it’d be on this:

Transformative AI becoming a reality would be an event on that scale. Like the arrival of agriculture 10,000 years ago or the transition from hand- to machine-manufacturing, it would be an event that would change the world for billions of people around the globe and for the entire trajectory of humanity’s future.

Technologies that fundamentally change how a wide range of goods or services are produced are called ‘general-purpose technologies.’ The two previous transformative events were caused by the discovery of two particularly significant general-purpose technologies: the change in food production as humanity transitioned from hunting and gathering to farming and the rise of machine manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution. Based on the evidence and arguments presented in this series on AI development, I believe it is plausible that powerful AI could represent the introduction of a similarly significant general-purpose technology.— Max Roser, Our World in Data

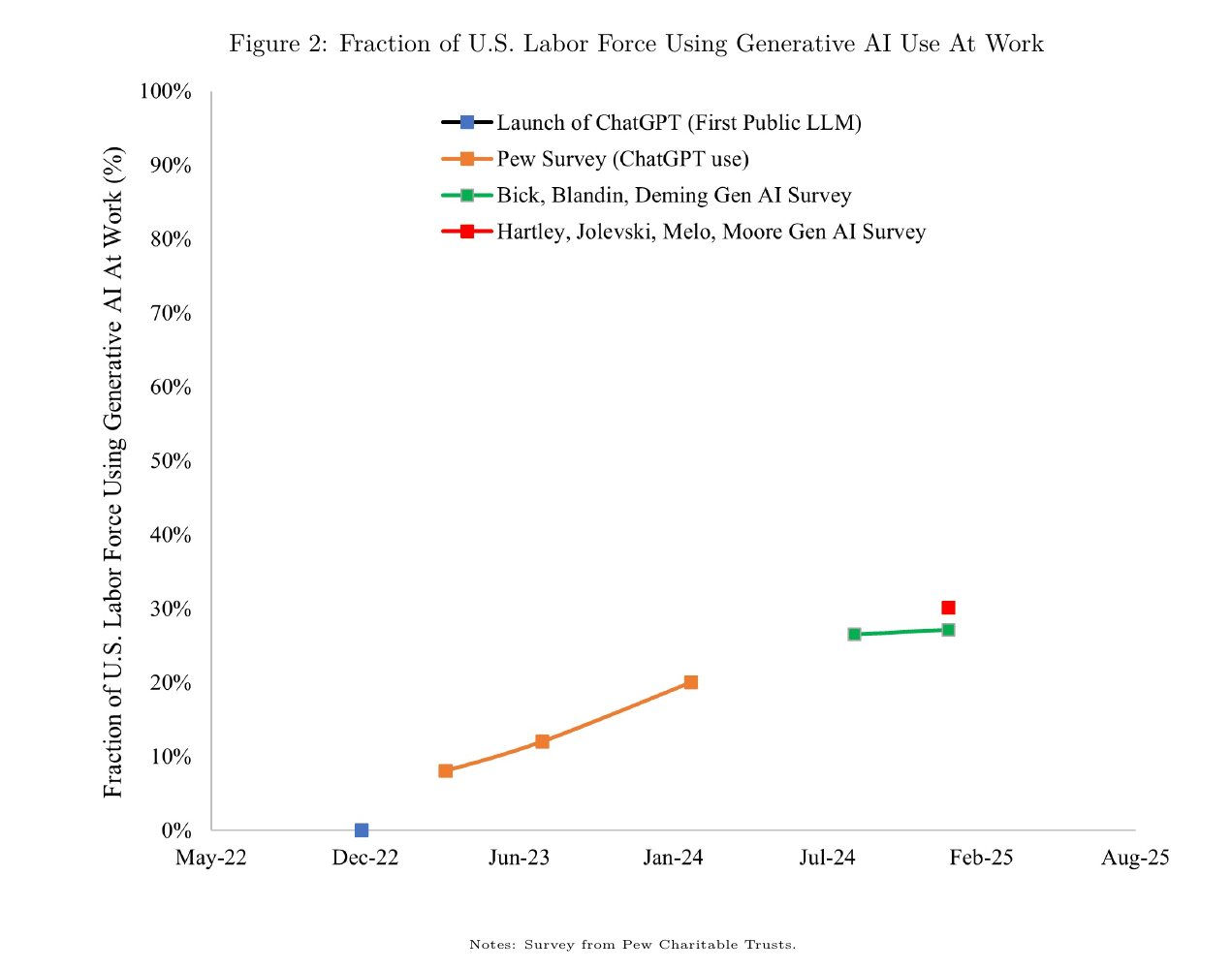

Given the potential for AI technologies to have a disruptive impact on labor markets and productivity, I’ve followed the economic literature in this area with great interest. One question I’ve been particularly curious about is the rate and pace of AI adoption. Sadly, we don’t yet have solid data on it—there’s some, but not a lot. The last good paper on the topic that I read was from Bick et al. (2024), and here are some high-level findings:

As of late 2024, nearly 40 percent of the U.S. population aged 18–64 uses generative AI. Twenty-three percent of employed respondents had used generative AI for work at least once in the previous week, and 9 percent used it every workday. Relative to each technology’s first mass-market product launch, work adoption of generative AI has been as fast as the personal computer (PC), and overall adoption has been faster than either PCs or the internet. Generative AI and PCs have very similar early adoption patterns by education, occupation, and other characteristics. Between 1 and 5 percent of all work hours are currently assisted by generative AI, and respondents report time savings equivalent to 1.4 percent of total work hours. This suggests that substantial productivity gains from generative AI are possible.

During a recent doomscrolling session at work—highly productive, of course—I came across this thread by economics researcher Jon Hartley, who coincidentally published a paper on AI adoption. Who said doomscrolling is bad?

Anyway, he and his colleagues conducted a survey of 4,278 U.S. workers on their usage of LLMs, and there were some interesting findings:

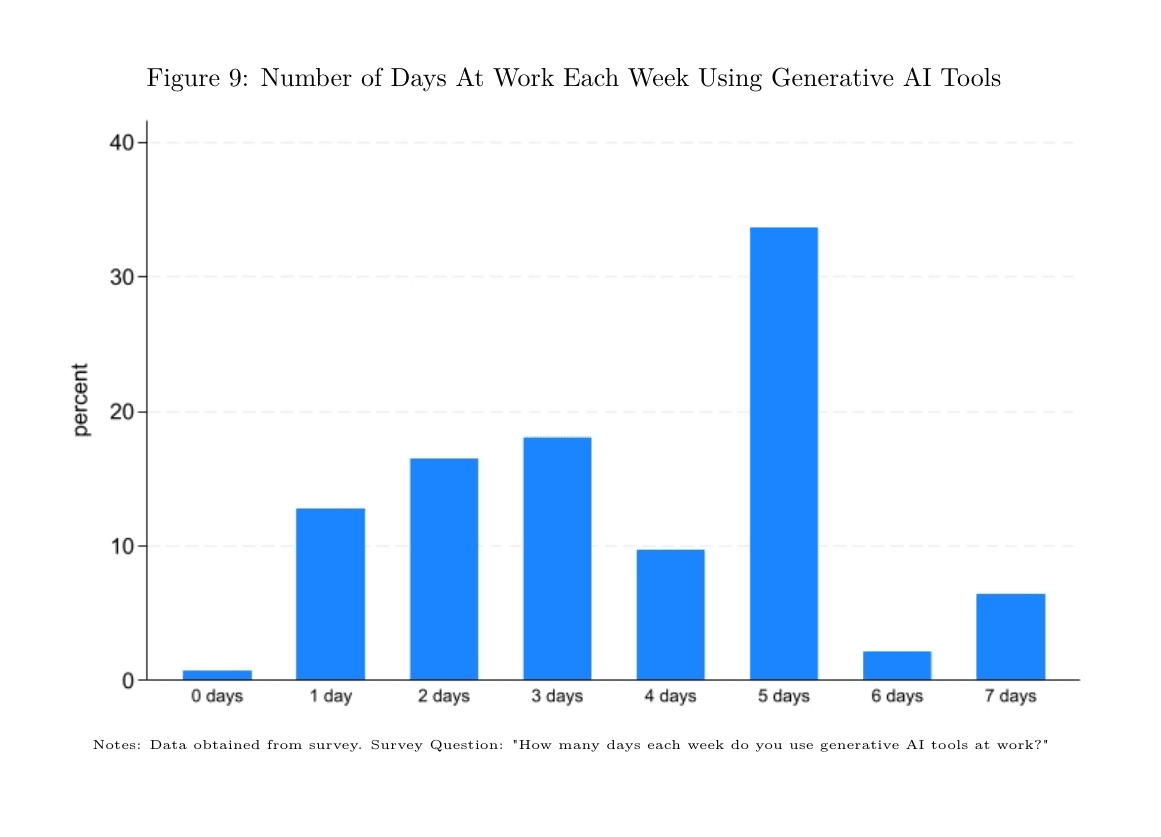

- 30.1% of respondents had used AI at work at some point since the launch of these generative AI tools. Among those, 33% used AI at work 5 days a week, 12% used these tools only 1 day a week, 17% used AI tools at work 2 days a week, and 18% used them 3 days a week.

- In most cases, workers spent less than 15 hours per week using AI tools.

- More educated workers are more likely to use AI tools. About 50% of respondents with graduate degrees and 37% with a college degree use generative AI tools, compared to only 20% with high school degrees.

- 50% of unemployed people reported using AI tools.

- By industry, the highest usage is in information services, company management, real estate, rental, leasing, construction, and education. As one would assume, workers in agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas, government, and the military used AI the least. We’re still some time away from saying, “Hey Claude, get the F out there and grow me some tomatoes and soybeans.”

- Higher-income workers tend to use AI tools more. 20% of workers earning below $50,000 annually use generative AI, compared to 50% of those earning above $200,000 annually.

- Men reported using AI more than women.

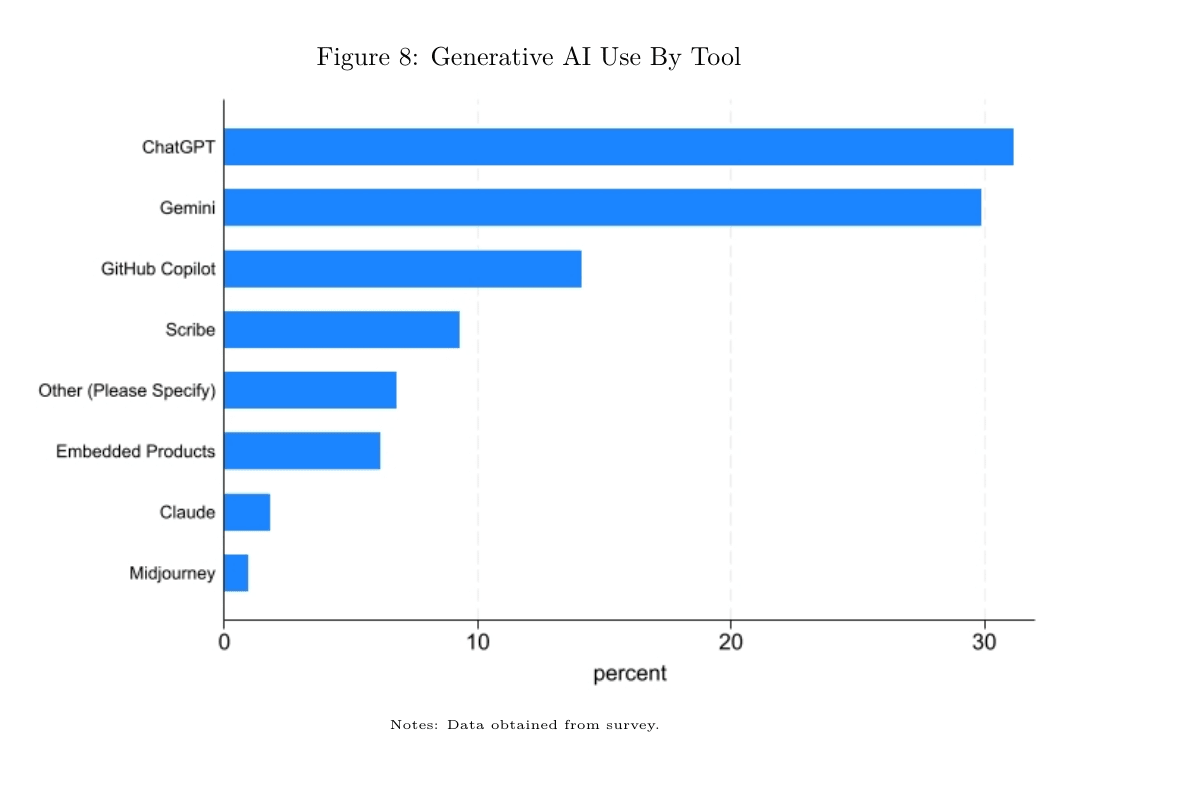

- ChatGPT was the most popular AI tool, with Gemini a close second, followed by GitHub Copilot.

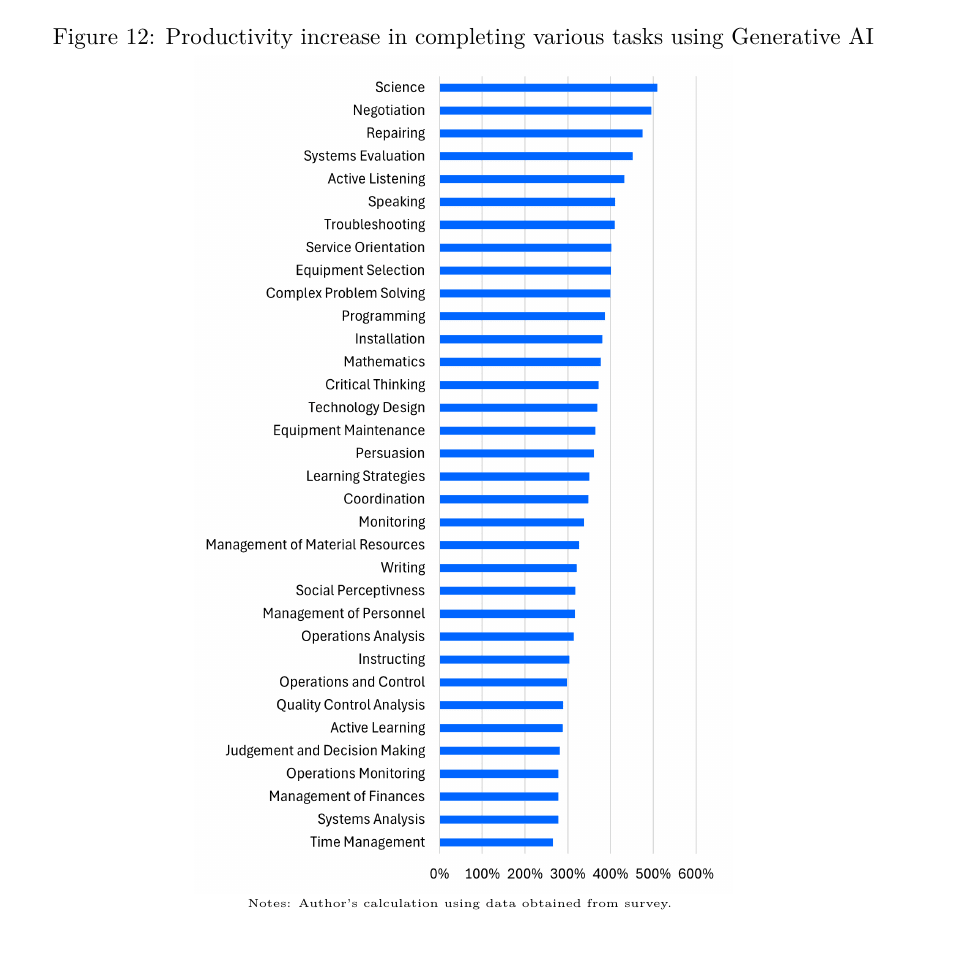

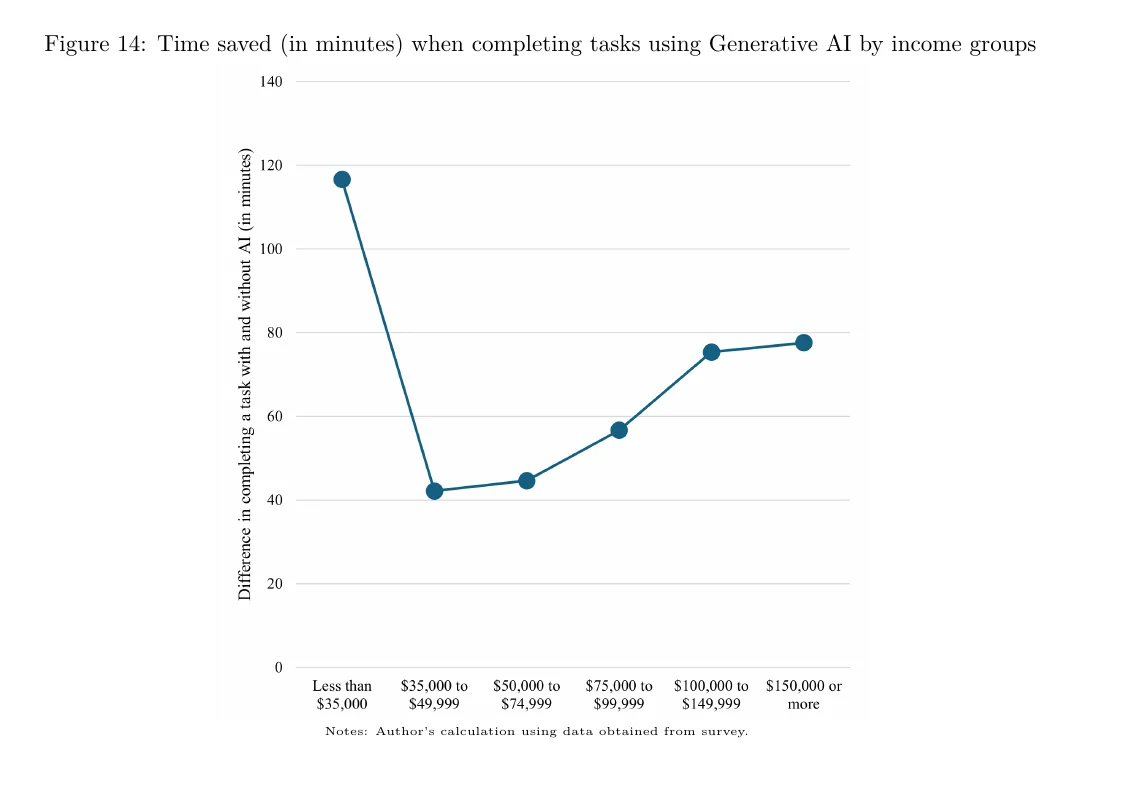

- Using AI tools helped workers save about 1 hour per task. A task that would normally take 90 minutes took only 30 minutes with AI. However, only about 16% of users said AI could complete the entire task on its own.

A Few Images from the Paper

Krishna—Another one bites the dust

At the end of 2023, I remember seeing a *Steve Jobs-*type launch video from a company called Humane, founded by former Apple employees. They introduced AI pins, which seemed quite innovative. Now, just over a year later, I’ve read that Humane is closing and HP is set to acquire parts of its assets for $116 million.

It also came to my attention—thanks to Bhuvan and Pranav—that HP has a less-than-stellar track record with acquisitions, such as those of Compaq and Autonomy. I haven’t dug deeper into that yet, though.

Tharun—It's good to zoom in on only one thing

In Nick Maggiulli's book Just. Keep. Buying. I came across an interesting story about focus. Jeffrey Seder, a Harvard-educated lawyer, discovered his passion for horses after a stable visit with his girlfriend. This passion became his profession.

After studying horses extensively, Seder made a breakthrough discovery: heart size was the decisive factor in racing success. Not bloodlines. Not pedigree. Not training methods. Just heart size.

Seder began performing MRIs on potential purchases, selecting horses solely based on heart size while ignoring metrics like bloodline, coat etc. This singular focus led him to identify American Pharoah, who would become the first Triple Crown winner in decades and one of the greatest horses in recent times.

Sometimes extraordinary success comes from identifying the one variable that truly matters while disregarding everything else as noise.

Seder's story is covered in this article if you want to go down the rabbit hole.

Pranav—How the NSE makes money

It’s a general shame that, working for one of India’s premier stock brokers, I haven’t the slightest clue how most of the stock market actually works. And the thing is, without knowing anything about the market, it’s really hard to know where to make an inroad from. “The shape of my ignorance”, as Bhuvan likes to call it, is infinite.

But last evening, a colleague sent us this report on India’s most valuable companies. We feature in a couple of places — including India’s most valuable unlisted companies. But topping that list, at many times our size, was the National Stock Exchange of India.

On one level, duh. Of course the NSE is many multiples as large as us. We’re just one of its many members. But at the same time, how does the NSE actually earn? And what does it do with all that money?

So, I sat with its annual report, and tried to break my head against this question (with the able guidance of ChatGPT, of course). Here's what I found:

Trading charges: Here's the most obvious one --- the NSE charges a transaction charge every time you transact on their platform. In Fiscal 2024, these charges alone netted it a massive ₹ 12,000 crore, which is ~80% of its revenue. This comes from ₹ 82,000 crore of turnover in the cash market, nearly ₹ 2 lakh crore of turnover in futures and options, and ₹ 30,000 crore of turnover in currency derivatives.

IPOs: When companies list, they bring in a lot of money for the NSE. Or, to be more specific, they bring in what is a lot of money for you and me, but chump-change for the NSE. First, they need to pay NSE a 'processing fee' to simply list. That, in itself, was ~₹ 50 crore in revenue in Fiscal 2024. It charges another ~₹ 50 crore for running the book building process. And then, it charges companies a small annual fee to stay listed --- pulling in another ~₹ 120 crore.

Colocation services: The NSE lets brokers place their servers in the exchange's own data centre. This gets you near-instant access to trade and price data. That comes steep, however. In Fiscal 2024, it netted almost ₹ 900 crore from colocation --- almost 6% of its revenue. At the same time, there are 60+ references to all the legal proceedings around the colocation scam in its annual report, so this is a bit of an albatross around the exchange's neck.

Data services: NSE charges market participants for all the data it gives them --- from KYC records to data on trades. That added ~₹ 280 crore to its revenue in Fiscal 2024. NSE also offers a data terminal. I'm not entirely sure what this is --- maybe it's like the Bloomberg terminal or something? Anyway, that was an extra ~₹ 60 crore in revenue in Fiscal 2024.

Clearing and settlement services: There's a lot of stuff that an exchange does at the back-end in order to play match-maker for trades. I don't understand this side of things, like, at all. But it honestly sounds like where all the magic happens. Anyway, NSE charges a fee for clearing and settlement as well, which brings in ~₹ 130 crore.

Indexes: NSE has a bunch of indexes where it clubs companies together --- by everything from market cap, to sector, to theme. It licenses these indices to entities that range from mutual funds to foreign exchanges, letting them run NIFTY-themed products. In Fiscal 2024, that brought in another ~₹ 100 crore.

Why am I breaking my head over a random annual report? Well, this is part of a larger project --- to understand how the stock market really works. Some day, this might end up in a gorgeous essay on everything about the stock markets. In the meanwhile, expect to see all sorts of random, nerdy, overly-detailed stock market tidbits.

Oh, where does all this money go, by the way (apart from, like, running the NSE)? Two things: One, it's sitting on an absolutely humongous treasury --- with more than ₹ 23,000 crore in cash and cash equivalents, and a bunch of other money it has stuffed away, besides. Two, it pays out a fairly hefty dividend --- ₹ 90 a share. I guess that makes sense for a professionally managed company.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.