Bhuvan—A Few Thoughts on India vs China

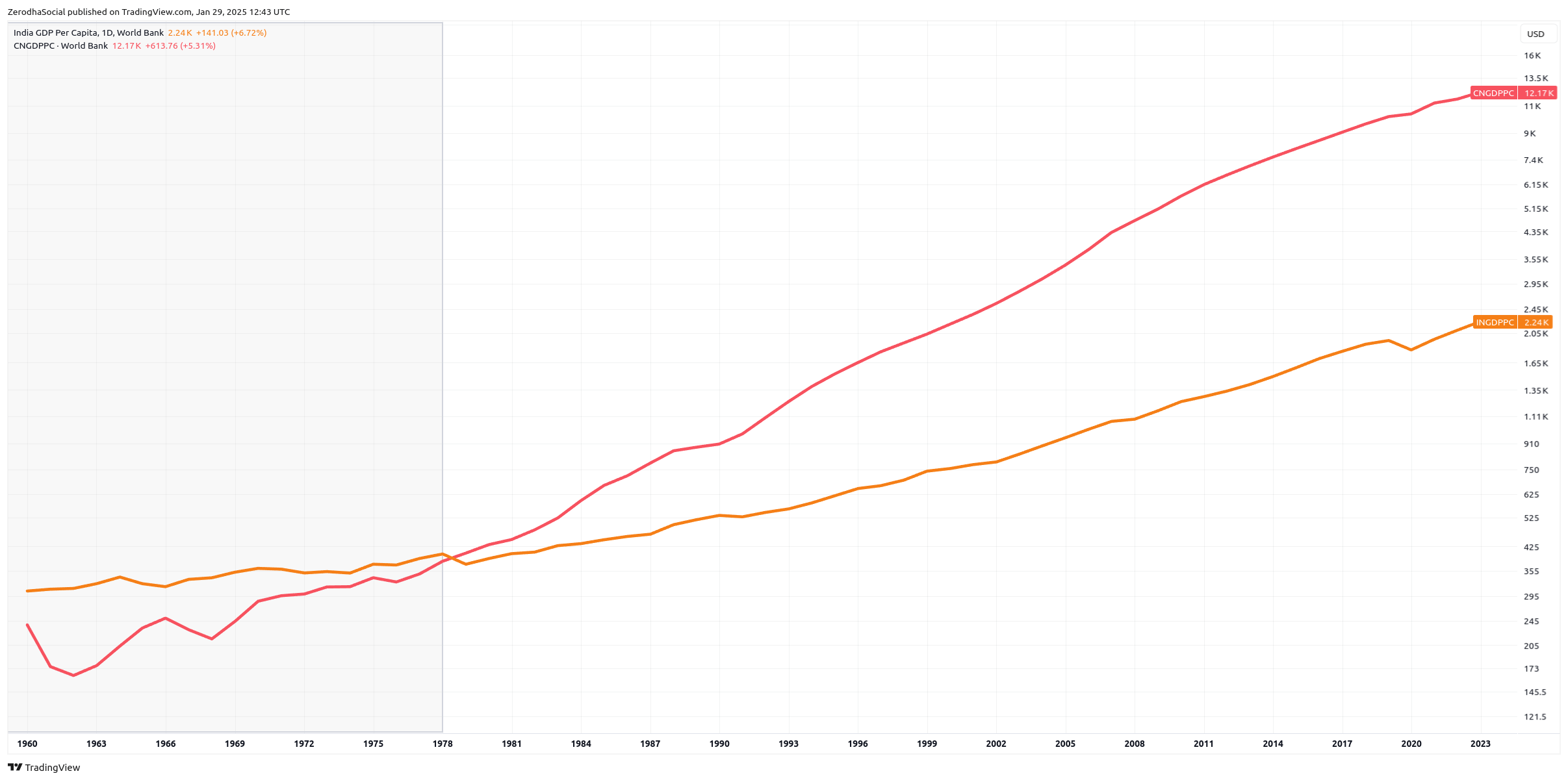

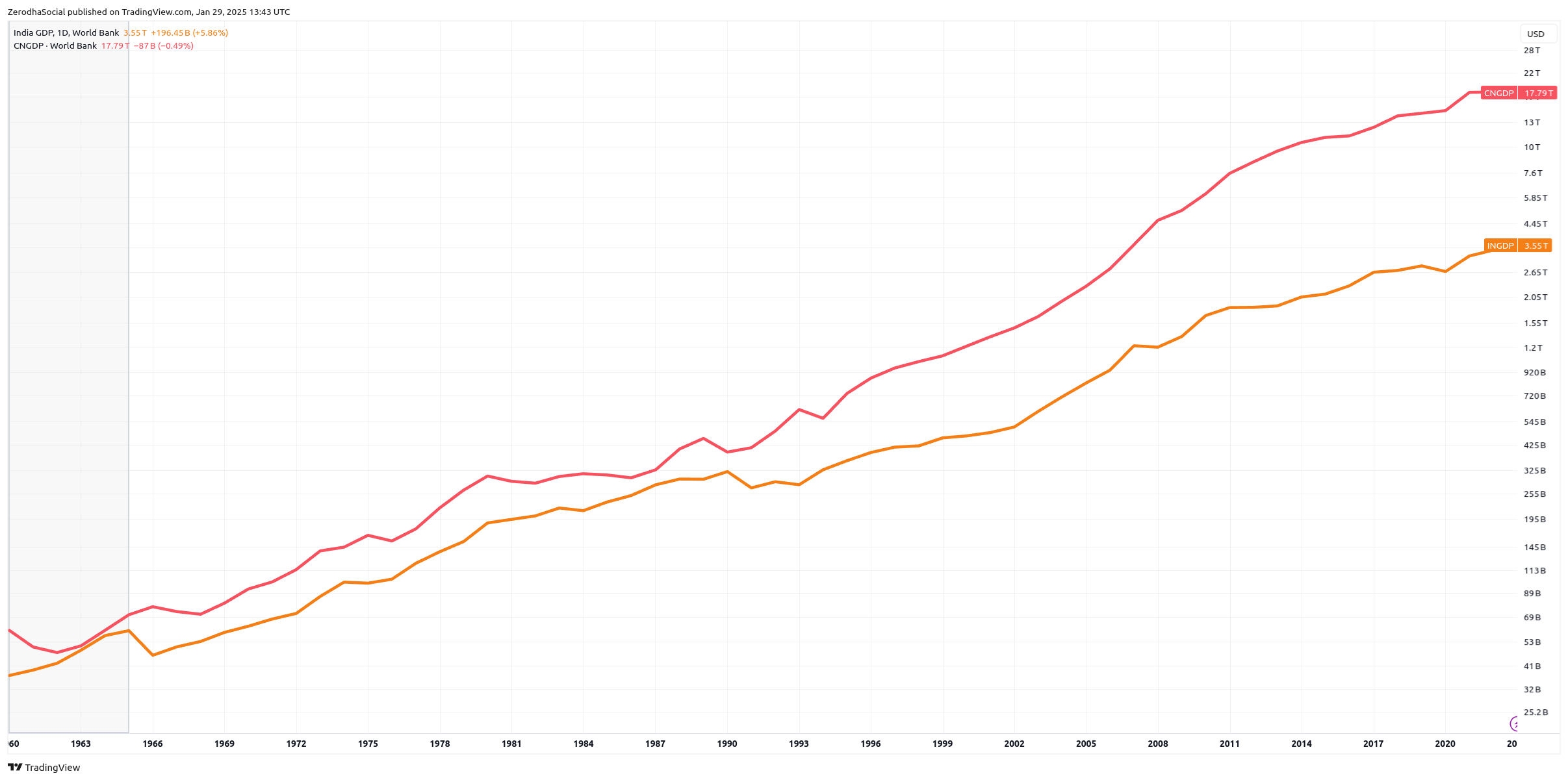

Often things become clichés because they are really good at conveying a point in a succinct manner. This applies to one of the most popular clichés of all: a picture speaks a thousand words. There are some pictures that speak more than a thousand words, and the image comparing India and China's GDP is one such image. I was thinking about this because Nithin shared this today. In the 1960s, both countries were at the same level and today, China's per capita GDP is five times larger.

In case you are wondering how this image would look like if you compared the GDP as whole, it's similar.

The question of why China overtook India is a complex one to answer. To give you a sense, Arvind Panagariya is of the view that China's success stems from its focus on industrialization, export-led growth, and liberalization to attract foreign capital. There's also the fact that in 1980, the share of industries in GDP was 48.5% for China and 24.2% for India. These starting conditions played a big role.

Meghnad Desai makes the case that China's single-party system, land reforms, focus on improving agricultural productivity, light and heavy industrialization, decisive and wholesale reforms, and high savings rate were key reasons. Perhaps one of the most thoughtful views is by Yuen Yuen Ang, Professor of Political Economy at Johns Hopkins University. She argues that the key factors were:

Top-down direction and bottom-up improvisation at the local level Mobilizing the vast bureaucracy Harnessing weak institutions Liberalization Prioritizing economic growth as the primary measure of success Incentivizing local officials to take risks Investments in literacy

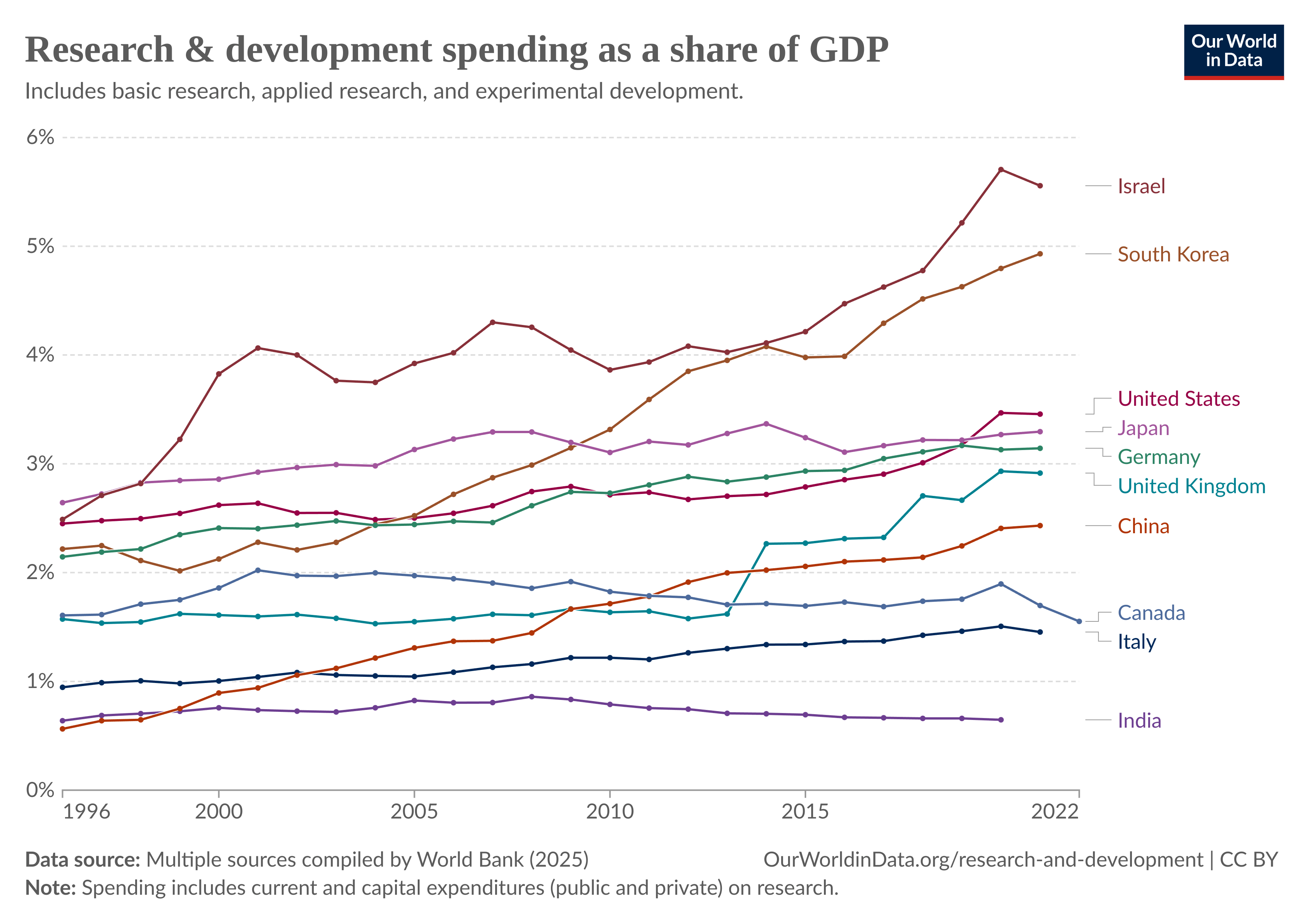

What's most interesting to me personally is China's massive investments in education, research, and development.

One of the big issues with comparing Chinese spending with other countries is the paucity of data. Having said that, based on the available data, China is one of the largest spenders, if not the largest, on research and development in the broadest terms.[ 1, 2 ).

I am pretty sure all these data points don't capture the hidden incentives and subsidies that China funnels into various parts of its economy. I don't mean "hidden" in a negative sense but more in the sense of disclosures.

China's drive to be self sufficient is a powerful one and even the harshest critic today has to agree that what they have achieved is nothing short of stunning. China is kicking ass in everything from AI, most semiconductors, electric vehicles, solar panels, wind, nuclear and more. None of this would've been possible with the dynamic research ecosystem that it has created. The pay offs from these investments are ridiculous. Despite complaints about wasteful spending, China is clearly doing something right. Kyle Chan who writes the awesome High Capacity newsletter, captures this perfectly:

In a number of cases, you have what I call "industrial coevolution" where two or more related industries develop together in an iterative, two-way process. This is happening now with China's EV and battery industries, which makes sense given how deeply dependent these two industries are on one another. China's EV industry leveraged the existing scale that China's battery manufacturing industry enjoyed, which in turn gave China's battery industry even more production volume and manufacturing experience. This is also happening with China's battery industry and its solar industry where solar plants are increasingly being deployed with integrated battery energy storage systems (BESS).

Industrial coevolution can also happen across multiple industries simultaneously: for example, China's lidar, EV, drone, and autonomous vehicle industries. And the co-development of this nexus of industries can have spillover effects into other industries, such as the proliferation of new kinds of autonomous equipment in agriculture, mining, construction, and energy. At the same time, if there's a weak link, China's central government (particularly the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology) might step in to support the lagging sector, even at the expense of connected industries. This is happening now with China's push to get its automakers to reduce their heavy reliance on foreign automotive semiconductor chips and switch to domestic alternatives.

From this Economist article:

Creating world-class universities and government institutions has also been a part of China's scientific development plan. Initiatives like "Project 211", the "985 programme" and the "China Nine League" gave money to selected labs to develop their research capabilities. Universities paid staff bonuses—estimated at an average of $44,000 each, and up to a whopping $165,000—if they published in high-impact international journals. Building the workforce has been a priority. Between 2000 and 2019, more than 6m Chinese students left the country to study abroad, according to China's education ministry. In recent years they have flooded back, bringing their newly acquired skills and knowledge with them. Data from the OECD suggest that, since the late 2000s, more scientists have been returning to the country than leaving. China now employs more researchers than both America and the entire EU.

According to the same article, China leads the world in terms of publishing high impact papers across physical sciences, environmental sciences and more. This is in large part due to explicit cash incentives by the government and it seems to be working. While most papers seem to be garbage because of the perverse incentive, there clearly is a positive side to it.

Meanwhile in India, there must be a sum total of 8 papers. I am exaggerating of course but the state our research and development is pathetic at best. I can speak to my own experience in trying to find economic and financial research papers—there must about 12 of them in total.

I don't know what the world of AI portends for India but I do know that if we continue to remain mediocre when it comes to harnessing some of the best and brightest minds we have in India, we have a bleak future to look forward to.

Tharun—The hunt for the perfect employee: Rarity of exceptional people

Have you ever noticed how companies are constantly searching for that one perfect employee? You know, the superhuman who can do everything - and they're willing to pay any price for them. If you're a manager, you've probably been on this hunt too. But here's the thing: finding this person feels impossible, right? Almost like searching for a unicorn.

Think about it - companies want someone who can:

- Learn, think, and solve problems quickly

- Stay responsible, organized, and hardworking

- Handle pressure like a pro and manage stress effortlessly

If you're wondering why your team seems filled with "just" average or above-average people, there's now actually a scientific explanation. Want to take a wild guess at how rare these perfect employees are? 1 in 100,000? Maybe 1 in a million? Well, you're close, but according to this scientific paper from Associate Professor Gilles E. Gignac from the School of Psychological Science at the University of Western Australia, it's actually 1 in 20 million! That means there are only about 400 such people in the entire world. Good luck finding them - you probably have better chances of stumbling upon an actual unicorn.

Now how was this study conducted?

The study looked at three key traits that predict success in work, life, and relationships:

- Intelligence: Your ability to learn, think critically, and solve problems

- Conscientiousness: Being responsible, organized, and hardworking

- Emotional Stability: Staying calm under pressure and handling stress well

So how rare are these "dream candidates" that companies keep searching for? Let’s break it down.

- Notable (Above Average - 16%)

These are your solid performers - quick learners who work hard and stay level-headed. They're the ones keeping companies running smoothly, even though they might fly under the radar for not being "extraordinary." But hey, being above average in all three traits already puts you in the top 16%.

- Remarkable (1 Level Up - 0.94%)

Now we're talking real standout employees. Less than 1 in 100 people hit this level. They're the ones who always think two steps ahead, never miss deadlines, and handle pressure like they're on a vacation.

- Exceptional (2 Levels Up - 0.0085%)

This is the super rare breed. We're talking 85 people in a million. These folks are learning machines with unmatched discipline and they stay cooler under pressure than Bangalore's weather. Think about it - in a city of a million people, you'd barely find 85 of them.

- Profoundly Exceptional (3 Levels Up - 1 in 20 Million)

Now we've reached the unicorn level - the employee every company dreams of. We're talking about someone who can perform magic on stage, play the guitar, dominate at badminton, make videos, AND maintain a six-pack... all while answering emails. I can do all of these, by the way. Oh, and did I mention their most important trait is being humble? Just like me - I'm incredibly humble and down-to-earth. You know, the most humble person you'll ever meet!

But jokes aside a profoundly exceptional person is not just a genius, not just highly disciplined, not just emotionally stable—but all three at the same time. With only 400 of these people on earth, the chances of you winning the Kerala lottery is higher.

Now why does this matter? Well because recruitment and employee expectations need to change.

- First, even finding someone who's above average across all three traits is much rarer than most people realize. Companies need to start appreciating these employees more.

- Second, recruiters should remember that just because someone's super intelligent doesn't mean they'll automatically be disciplined or emotionally strong. It's like assuming someone who's great at singing will also be great at cooking.

So to all the companies and managers, stop chasing unicorns and start appreciating your above-average employees. They're already more special than you might think.

Also, if in your next appraisal your manager tells you were "above average but not exceptional," send them this article :)

Krishna—The man who vanished billions

Hopefully, tomorrow brings something that has nothing to do with DeepSeek for a change.

Today, I came across an article by Gregory Zuckerman, the author of the well-known book on the late Jim Simons—the man behind Renaissance Technologies, who generated extraordinary returns of around 66**% annually over 40 years.** There’s a nice Acquired episode on this.

In his article, Gregory mentions that he hadn’t read much about DeepSeek, nor had he been following it. So when people were tagging him on social media on stuff related to DeepSeek he thought it was some kind of altcoin. Turns out, the reason was that Liang ****had written the preface to the Chinese translation of Gregory’s book.

Liang wrote: “Whenever I encounter difficulties at work, I recall Simons’s words: ‘There must be a way to model prices.’”

The man, Liang, whose side project wiped away billions from US’s market is a big fan of the man who solved the markets.

The Guy Behind DeepSeek Blurbed My Book in China

Anurag— Working women in India

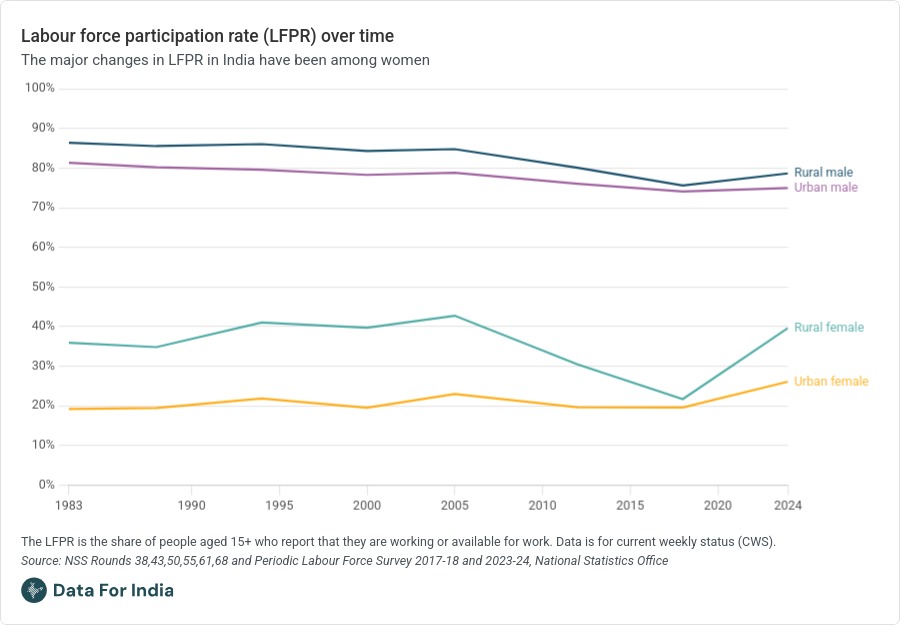

I recently read about how more women in India are joining the workforce again. After staying low for years and dropping sharply after 2005, female labour force participation has picked up once again in the last five years. This, of course, is a big shift because, for a long time, women in India have been underrepresented in the workforce.

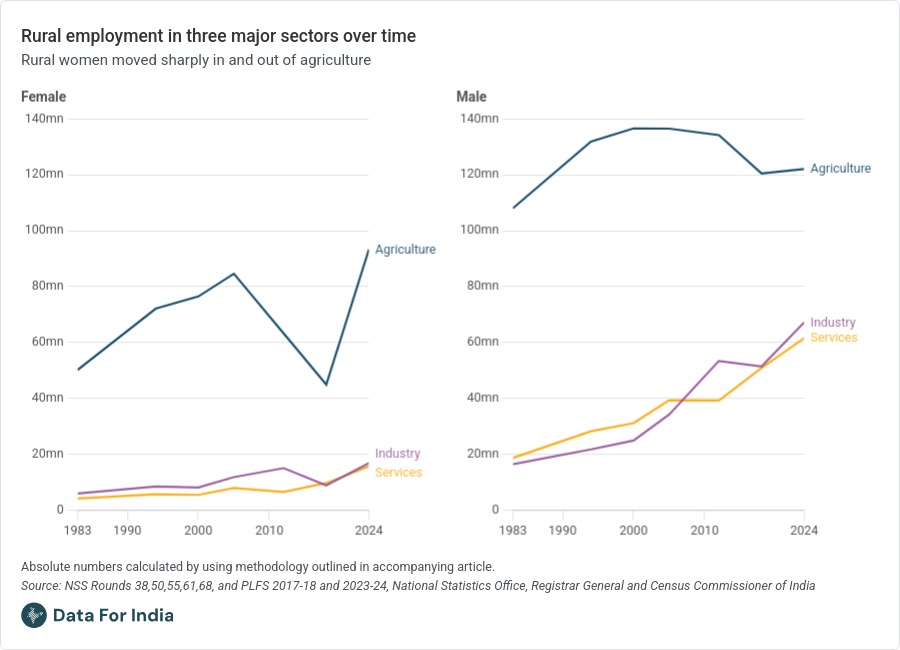

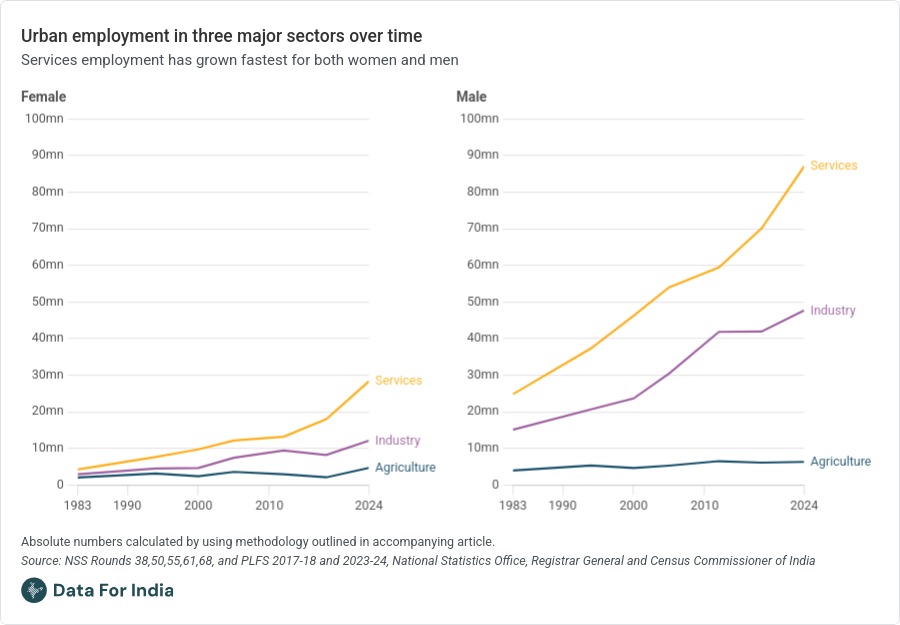

Men in India have always had much higher participation in the workforce than women, nearly twice as much. Over time, male participation has slightly declined, while female participation has gone up and down more sharply. Among women, rural participation has been more unpredictable than urban. Rural women have always been more likely to work, but after 2005, many of them left the workforce, mostly because they moved out of agriculture. Recently, 50 million rural women have returned to farm work, bringing their participation back to early 2000s levels. In cities, the increase has been slower but steady, mainly due to more job opportunities in the services sector.

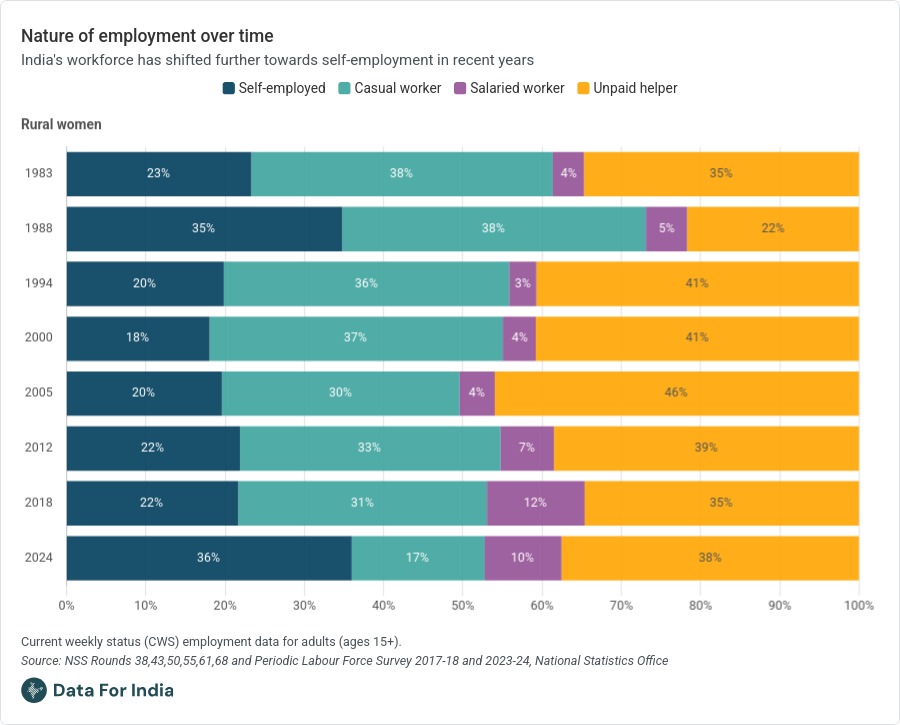

One big reason women move in and out of the workforce is household work. When fewer women work, more of them say their main activity is taking care of their homes. When more women work, fewer report being engaged in housework. Right now, the number of women listing housework as their primary activity is the lowest it has ever been.

The kind of work women do has also changed over time. In the 1980s and 1990s, many rural women worked as unpaid helpers in family farms or businesses. By 2005, nearly half of all working rural women were unpaid helpers. But the recent rise in female employment has been different. More women are now self-employed, meaning they are earning their own wages rather than working without pay. While agriculture still dominates in rural India, urban jobs have increasingly come from the services sector, which has been growing steadily for both men and women.

Men’s participation in the workforce has slightly declined, but for a different reason. Since the 1980s, more men have been enrolling in education, which has gradually pulled them out of the workforce. Unlike women, most men have historically worked, so their exit has been slower and mainly due to studying.

Another key trend in India’s workforce is the rise of self-employment. More workers, especially women, are choosing to be self-employed rather than working salaried jobs. This shift is happening in both cities and villages. In rural areas, most of the recent increase in female employment has come from short-term or seasonal work. In urban areas, the rise in employment has mostly been in long-term jobs.

Even though India’s female workforce participation is still low compared to other countries, the recent increase shows a change in social and economic trends. With more women earning their own income and becoming self-employed, the way work looks in India could very quickly be evolving.

Pranav—You are the market

I didn't learn very much today.

But as a former capital markets lawyer, this Buffet quote I just came across made a lot of sense to me:

“An IPO is like a negotiated transaction - the seller chooses when to come public - and it's unlikely to be a time that's favourable to you.”

We never saw anybody IPO when the market sentiment was down. Our work would only heat up when the markets were hot, and as bull runs extended, we would come under more and more pressure.

Every important decision maker in the process - promoters, senior officials (especially if they held ESOPs), investment bankers, all the way down to the law firm lawyers - everybody gains from a dhamaka listing. Nobody gains from a fair one. If a big listing doesn't seem likely, you call your IPO plans off and wait.

You do not time the IPO market. The company times the IPO market - you are the market.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.