Pranav—India’s statistical system

I’ve been making my way (very, very slowly) through Karthik Muralidharan’s ginormous Accelerating India’s Development. It’s an incredible book — reading it almost feels like national duty, so rich is it with insight on the monstrosity that is the Indian state.

That said, I’m not really in a state where I can give you any of those big insights today. The ol’ 9-5 fried all my mental GPUs today. So, instead, here are some random facts about India’s statistical system. Not the quality stuff you come here for, I agree, but hey — it’s something I learned today!

So, here goes:

- India’s statistical machinery sits in its National Statistical Office. But really, that’s two entities. There’s the Central Statistical Office, which looks at all the big macro numbers — GDP, inflation, that sort of thing. Then, there’s the National Sample Survey Organisation, which tries to understand the country through — you guessed it — sample surveys.

- India’s statistical machinery was globally acclaimed, once upon a time. The World Bank shaped its own Living Standards Measurement Survey on what the NSS did. Over time, though, it got knee-capped. You have to wonder if this is the tragic direction in which our DPIs will head some day.

- The NSS is excellent for gyaan and horrible for everyday governance. That’s for three reasons: (a) data’s collected at a five year cycle, which is simply not relevant for day-to-day decision-making, (b) there isn’t enough spatial disaggregation to really understand things on-the-ground, and (c) it doesn’t really ask the important questions — for instance, it might ask if a kid goes to school, but not if they’ve actually learned anything.

- Because of all this, while the government can measure inputs, it isn’t very good at understanding outcomes. So, for instance, in 2000, it set out to enroll all children in school — and it succeeded! That said, 50% of Class 5 children can’t read Class 2-level texts, because we didn’t really check if our schools were working. So you have 100% school enrollment, but 50% effective literacy.

- Similarly, we have no way of knowing what citizens’ experiences with public services are like. So nearly a third of Jan-Dhan beneficiaries believed they hadn’t received money, or had no idea that they had — all because we have no way of figuring this stuff out.

- The vast majority of government data comes from its administrative records. Only this is often… well, made-up bullshit. So, for instance, the MP education department began testing every government school student every year. And this got a whole lot of acclaim — NITI Aayog even labelled it a ‘best practice’. Only, when independent researchers asked the same students the same questions a few weeks later, they all flunked. That’s when we realised how obviously made up it all was — according to the survey, for instance, all students scored 65% in Hindi across the board.

- So why don’t we do a better job of data collection? Karthik points to four things: (a) data collection is seen as an expensive luxury, that nobody wants to spend precious department resources on; (b) government employees don’t have the technical expertise to collect data, and have to rely on donors or consultants — which means you can’t do anything regularly; (c) government officials have too short a tenure, and so, data collection doesn’t make sense to any particular official, even if it’s good for the health of the overall organisation; and (d) if you shine light into a gutter, you’ll see shit — and it’s in nobody’s interest that you do so.

I guess this was pretty insightful after all. How about that!

There’s a lovely anecdote he mentions. Rukmini Banerjee (CEO, Pratham) once pointed out to village officials that their statistics on education were clearly wrong. Pat came the reply — “Madam, aapko asliyat se itna lagaav kyun hai?”

We aren’t serious people, are we?

Kashish—Why do I sound so melodic during my bathroom singing sessions?

I went to a bar the other day with my friends, and luckily, it was Karaoke night. Now, I don’t usually sing in public—because, well, I know I’m terrible. But for some reason, I decided to give it a shot. Maybe it was nostalgia for my bathroom singing sessions, where I always sound amazing. I knew I wasn’t great, but surely, I couldn’t be that bad, right?

Turns out, I was completely wrong.

The next day, my friends sent me a video of my performance, and I cringed so hard I wanted to disappear. I needed something—or someone—to blame. And then it hit me: it was my bathroom. My bathroom singing sessions had given me the false confidence that I could actually sing.

This led me down a rabbit hole to figure out why I sound so much better in the shower.

Spoiler alert: the rabbit hole wasn’t that deep. It all comes down to one thing—reverb.

Reverb is an audio effect that creates a natural echo, and it does two magical things for a bad singer like me:

- It makes your voice sound fuller. The echo creates the illusion that your voice is being projected in a large, open space, adding depth and making it sound richer.

- It smooths out imperfections. As your voice mixes with its own echoes, little mistakes in pitch or timing become less noticeable. The notes blend together, making even an untrained voice sound more fluid and melodic.

Basically, reverb gives your voice more depth and helps mask all the out-of-tune, off-beat moments.

How does my bathroom create such an acoustic environment? The hard surfaces—like tiles, walls, and mirrors—don’t absorb sound but instead reflect it, allowing it to linger a little longer before fading away, causing the reverb.

What did I learn today? it’s not me, it’s my bathroom that’s the source of my award winning performances.

Tharun—How reducing pollution is increasing global warming

Efforts to clean up our oceans might be accidentally speeding up global warming. Umm, but how, why? I had the exact same question when I came across this article from Financial Times, and I tried my best to understand it and now I'm trying my hand at explaining it. I am by no means an expert but here is what I have understood.

In 2020 the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) decided to reduce sulphur emissions from ships. While this move was intended to reduce the pollution from our oceans, climate scientist James Hansen has raised some concerning questions about its second order effects.

To understand this, let's first look at how sulphur actually affects our climate. When ships release sulphur, it creates something called sulphur aerosol - think of these as tiny, invisible particles floating in the air, similar to dust. These particles actually play an interesting role in protecting our planet from heat. It's a bit like holding up a thin umbrella on a scorching hot day - while it won't make the day cool, it definitely helps reduce the heat you feel on your body.

Hansen argues that by reducing the sulphur content in ship fuel - a well-intentioned move to curb ocean pollution - we have accidentally removed this protective "umbrella" over our oceans. With less sulphur aerosol in the atmosphere, more sunlight is now reaching and heating our oceans.

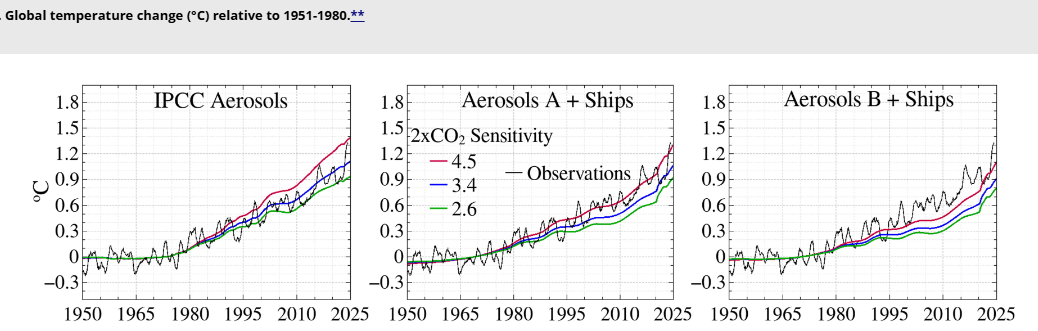

This could be the potential explanation for why you feel like there are two seasons now: summer and very hot summers. Scientists had predicted that the effects of El Niño (a natural warming phenomenon) would begin to decrease, but January 2025 remained the hottest January ever recorded. This suggests that even as El Niño's influence should be reducing, temperatures aren't dropping as expected. Hansen believes the reduction in sulphur aerosol could be the reason why we'll continue to see rising temperatures, making the international goal of limiting global warming to 2°C essentially unattainable.

Hansen describes this situation as a "Faustian bargain" - a bad deal where humanity temporarily benefited from the cooling effects of air pollution while continuing to emit greenhouse gases. Now, as we clean up certain types of pollution (which we absolutely should), we're starting to see the full impact of our greenhouse gas emissions. If you wish to do a deep dive, you can find Hansen's research paper here.

However, it's worth noting that not everyone thinks similarly. Some scientists argue that Hansen is overestimating the impact of reduced sulphur aerosol on global temperatures.

Krishna—De minimis

Say you live in the US and go to Shein or Temu and order stuff worth $500. Normally, since it’s coming from outside the country, customs would check it and put some taxes on it because it's an imported product. But back in 2016, the US changed a rule saying that if your package is valued at $800 or less, there will be no import taxes. Great, right? Because customs checks, shipping, and deliveries all became faster.

But obviously, companies like Shein found a loophole. They realized, "If we keep packages under $800, we don’t pay any US import taxes or fees." So, they split large shipments into many small packages to stay under that limit. This way, they save money and offer cheaper prices to you.

Now, here’s where de minimis comes in. The rule that allows packages under $800 to skip import taxes is called the de minimis threshold. “De minimis” basically means “too small to bother with”—like, customs won't sweat the small stuff.

But why am I bringing this up now? Because in the last couple of days, the US government has removed the de minimis exemption for Chinese imports. This means all packages from China, even under $800, will now face import duties and taxes. This is a big deal for sites like Shein and Temu, which rely heavily on this rule to keep prices low. Without it, prices could go up, shipping might take longer, and you might not get those crazy deals as easily.

In short, the de minimis rule helped these companies avoid taxes, but now that loophole has been shut down. This could completely change how cheap imports from China work in the US.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.