Bhuvan—Democratic backsliding and collapse of Russian regime

I'm a huge fan of the eminent historian Stephen Kotkin, and whenever I see an interview of his, I always try to watch. His latest appearance was on the Uncommon Knowledge podcast, where he talked about Trump winning the presidency and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, among other things.

A few things stood out to me from the podcast.

Democracy did well in 2024, regardless of what you think, but it doesn't feel like it, does it? I loved the point Kotkin made about people confusing their preferred candidate losing for erosion of democracy.

Stephen Kotkin: Sure, in some cases, the polls aren't legitimate, like in Russia, but in most cases, they are. This year, half of the adult population of the planet was able to voice their views. If you're a proponent of democracy, this has been one of the greatest years ever for it. Yet, much of the conversation is focused on the "crisis of democracy," threats to democracy, democratic erosion, and democratic backsliding. So, what’s going on here?

Let’s look at the American case. Many analysts confuse the rejection of their preferred candidates at the polls with a "crisis of democracy."

Peter Robinson: Do they ever?

Stephen Kotkin: Yes, it’s a sad but pervasive phenomenon. There can certainly be crises in democratic governance, and there were important issues this year. But when over 2 billion adults—eight of the ten most populous countries—get to vote, something good has happened. That’s the first and deepest point to make.

Stephen Kotkin: It was a great year for democracy, and the narrative of democratic erosion and backsliding took a hit. The other group that took a beating were incumbents—across the board. Incumbents of all kinds were affected. And that’s because government isn’t working well. It’s not working well for the majority of people. It may be working for some, but not for enough. As a result, incumbents on both the right and the left took a hit.

On a separate note, here's a paper that will give you some hope:

This article introduces a new type of regime transformation, “U-Turn.” U-Turn is a two- directional process where autocratization is closely followed by democratization and the two are interlinked. With the systematic identification of U-Turns, we show that there were 102 such episodes of regime transformation between 1900 and 2023. Our analysis also demonstrates that U-Turns are common – 52% of all autocratization episodes transmuted into U-Turns within no more than five years after their end. Even more notable perhaps, the share of U-Turns has increased to 73% during the contemporary “third wave of autocratization.”

Dissecting the varying paths U-Turn episodes take, our analysis demonstrates that 94% of all cases become an autocracy at the “bottom.” This holds true also for the subset of episodes that start in democracies. In 39 of the 45 such cases, democracy broke down for a short period before autocratization was reversed, and almost all of them (33 out of 39, or 85%) became democracies again by the end of the U-Turn episode. In other words, a democratic breakdown does not necessarily prevent a return to democracy, especially if autocratization is halted and reversed relatively soon – the average time for turnarounds is about five years after the onset of autocratization.

Kotkin is one of the most insightful experts on all things Russia, having written the definitive biography of Stalin. A lot of what I know about Russia comes from listening to him. The other part of the conversation that stood out to me was this: despite the horrible costs Putin has imposed on the Russian people, why is he still in power?

Kotkin cites a few reasons:

- Collective action problem: In authoritarian regimes, paranoia is pervasive. People are afraid to speak out against leaders because they fear being ratted out.

- Negative selection: Putin has appointed incompetent idiots to key positions of power. The advantage of incompetent people is that they are too stupid to know they are incompetent, which means they'll never revolt or even think about usurping power.

Stephen Kotkin: The cost of negative selection is that you end up with incompetent people in key positions, like defense minister. This might be fine during peacetime, but when war comes, you've consistently chosen loyalty over competence. And you've done so deliberately, through negative selection. War has a way of exposing people's true capabilities.

It's similar to how all doctors seem great until you actually get sick.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Stephen Kotkin: As soon as you get sick, you realize some doctors aren’t as good as you thought. Similarly, when war comes, you discover that your loyalists may not be competent, but they are loyal. And, crucially, they lack the skills to challenge you. But remember, the person in charge controls the military—those forces can threaten your regime. So, often, the most incompetent people hold the most powerful positions in these regimes, which complicates any effort to remove someone like Putin or make him pay for his mistakes.

In addition to fear and the collective action problem, think about Mubarak's regime.

Peter Robinson: You mean Hosni Mubarak, the former president of Egypt?

Stephen Kotkin: Yes. He was old, had cancer, and his son, Gamal, wasn’t taken seriously as a successor. The military men he promoted were unimpressive, which is why he put them in those positions. When the time came, they hesitated, did nothing, and couldn't move against Mubarak to save the country—even though he was 80, had cancer, and his son was a non-entity. Why? Because those military leaders were non-entities themselves. That’s the second problem.

One of the more interesting points Kotkin makes is about the U.S.'s refusal to apply pressure and push for regime change. The U.S. has explicitly said that regime change is off the table, but it's getting accused of it by Russian propaganda anyway. So the U.S. is being accused of something it isn't doing—should it not be doing it then, given that it's paying the price regardless?

Stephen Kotkin: So, if Putin feels a direct threat to his regime, domestically, you might see him agree to an armistice or a deal that is acceptable to Ukraine and our European partners. But from the start, we took one option off the table: pressure on Putin's regime.

Peter Robinson: Russia.

Stephen Kotkin: Yes, we ruled that out because it was seen as escalatory. It could potentially lead to direct conflict between the U.S. and Russia, or between NATO and Russia. So we decided to leave that option aside. Instead, we’ve escalated on the battlefield, where Putin is stronger—he has more troops and doesn’t care about their lives. He’s willing to sacrifice them.

And so we find ourselves in a war of attrition, fighting alongside a smaller, quasi-democratic country against a much larger, authoritarian regime that doesn’t value life. We’ve escalated on the battlefield—maybe slowly, as some critics say—or maybe not doing everything we could have, according to those same critics.

But still, we've taken the escalatory risk on the battlefield, while refusing to escalate politically. We avoided that escalation because we feared it would be too dangerous. So, where are we now in the war? We haven’t applied enough pressure to his regime.

Now, keep in mind, we’re constantly accused of aiming for regime change by Russian propaganda, even though we haven’t taken any concrete actions toward that. We’re being accused of regime change while doing nothing to pursue it, and we’re escalating on the battlefield anyway. And yet, here we are.

I highly recommend watching the full video.

Krishna—White people don’t believe in India growth story?

So, I was doing some reading for my show Who Said What? There are always people saying stuff like “FIIs are selling at all-time highs… the market’s gonna fall!” I've heard this plenty of times. I already had a basic idea of why this happens, but today I went down a rabbit hole—an hour of random scrolling and reading—to understand it better.

Before we dive in, just a quick PSA: this is based on my totally scientific one-hour research session, so take it with a pinch of salt.

At the core, what’s an investor’s job? Simple: make money. Whether it's by buying and selling wine, stocks, or real estate, the how doesn’t matter. The goal is to make money—or, in fancy terms, to generate alpha (basically earning better returns than the market).

Now, when we talk about Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) selling Indian stocks, it's often not because they’ve suddenly lost faith in the India growth story or because valuations look bad. It’s usually because somewhere else looks more attractive, thanks to factors that have little to do with India. Let me break it down:

1. The Dollar and US Treasuries

The US dollar is the world’s reserve currency. That means when things get shaky, people trust it the most. When US interest rates rise (usually because of the Fed trying to control inflation), investors can park their money in US treasuries—government bonds that give around 5-6% returns.

Treasuries are considered risk-free because the US government guarantees them. Compare that to investing in India’s stock market, which might give you a 10% return. Sure, 10% is higher, but it’s not guaranteed. The market could tank tomorrow.

So, if you were an investor, would you go for the safe and steady 6% or risk it all for a potential 10% in an emerging market? Many funds—especially the risk-averse ones—choose the safer bet. As more investors rush to US assets, the dollar’s value goes up, making it even harder for emerging markets to compete.

2. Taxes and Currency Risks

Here’s the other issue: India’s tax laws. Let’s say Nifty gave you a 9% return last year. Once you deduct taxes and factor in currency depreciation (if the rupee weakens against the dollar), your profits shrink fast. So now, instead of the shiny 9-10% return you were expecting, you're left with much less. Suddenly, those US treasuries at 5-6% don’t seem so bad anymore.

3. Short-Term Trading Strategies

Some FIIs are not in it for the long haul. They follow short-term trading strategies based on global trends and market cycles. For example, they might buy up India’s IT stocks because there’s hype around AI and tech globally. But when that hype fades or they hit their profit target, they exit—sometimes all at once—without it having anything to do with India's economy.

Pranav—India’s journey to becoming a basketcase

This Monday, we’re back to Doug Irwin’s paper on India’s liberalisation journey. It’s really a fascinating read, because you see all the rookie macroeconomic mistakes we made — and are still tempted to make every once in a while.

Once again, here are my notes, peppered with tons of my own commentary.

Why did we begin with a state-led economy in the first place?

A couple of reasons:

The official reason: India had limited resources. The way to deal with limited resources, the thinking went, was to plan how they’d be used. We wanted to race towards industrialisation (understandably so), and capitalism seemed like waste and profligacy.

The emotional reason: We had come to associate commerce with the likes of the East India Company. Businesses were, in the logic of the times, parasites that came and exploited your people for their gain.

Our entire crisis seems to be set in motion by one big policy mistake...

...all the way back in the late '50s: capital-intensive industrialisation, a goal of the second five-year plan.

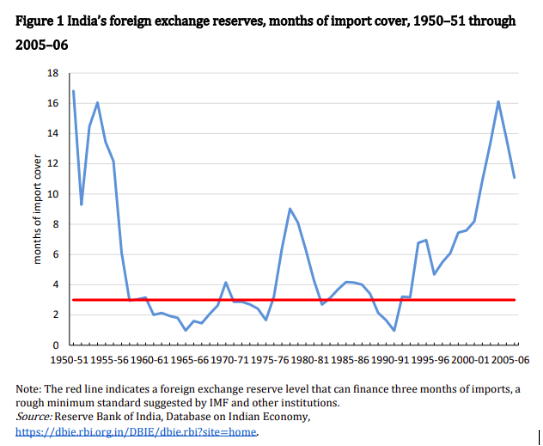

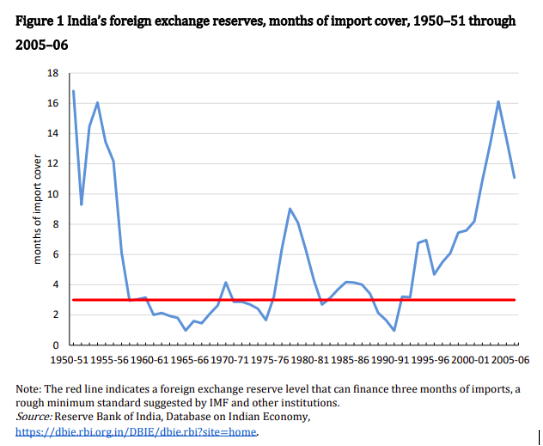

To set up India’s initial factories, we needed to import capital goods. That required foreign exchange. Imports shot up 40% while exports remained flat. Our newly created industries simply didn’t find buyers, and didn’t earn the forex we needed to fund our plans. That sparked a forex crisis.

How bad was it? In just three-fourths of a year, we spent all the forex we thought we’d spend in five years. Planning rarely works, does it?

What’s worse is that we never really grew out of this crisis. We were plagued by forex problems until liberalisation.

For more details: Read the paper here

Here’s the kicker: our early leaders didn’t believe in a floating foreign exchange rate.

What we needed: Restrict imports, boost exports. A floating exchange rate could do that automatically, stopping the bleeding of foreign exchange.

Instead, we kept a fixed exchange rate against the Pound and Dollar, despite higher inflation and demand pressures. The Rupee’s value kept falling in reality, but stayed artificially high. We became addicted to foreign aid.

Naturally, a black market sprang up. The premium climbed from 5% (early '50s), to 20% (late '50s), to over 50% (early '60s).

Nehru dismissed a floating rate as "fantastic nonsense." That’s India’s great tragedy: economic illiteracy. Poor countries need to understand scarcity the most, yet often learn the least.

The only answer? Controlling imports.

Forecast everything: Every year, we tried to forecast our forex situation, allocate it between government and private entities, and license every single import.

Monopolies: The government gave monopolies to state entities to import essentials. The private sector got scraps of forex.

Import restrictions: Import licenses and quotas were enforced. Consumer goods were considered non-essential and banned. Importing for resale wasn’t allowed—only for personal use.

Crisis of 1957: The forex crisis led to an import squeeze. The government didn’t ease up until liberalisation.

Corruption: An overly complicated system invited corruption. By the mid-'60s, rent-seeking accounted for 7% of GDP.

The first devaluation

By 1960, we had: (a) a fixed exchange rate overvaluing the Rupee, (b) a state-led economy, and (c) severe import restrictions.

Military and food imports in the next decade gutted our forex reserves. The black market premium hit 130%.

India devalued the Rupee in 1966, in exchange for aid from the World Bank. Numerology-loving Indians saw "6-6-66" as a bad omen. Devaluation triggered backlash.

The devaluation came too late and wasn’t enough. Back-to-back droughts made food imports expensive. Congress lost 78 seats in the 1967 elections.

Things get worse: The Indira Gandhi years

In 1969, Indira Gandhi aligned with the Left. Investment was restricted, industries were nationalised, and imports became even more restrictive.

India became known as the most autarkic non-communist country. The "Hindu rate of growth" prevailed. Forex concerns dominated, but we didn’t understand the root causes.

Briefcase politics: Privileges and exemptions were bought through party donations.

Reform by stealth

The 1970s saw slight improvements due to remittances from emigrants and quiet de-linking of the Rupee from the Dollar. The Rupee was tied to a basket of currencies, allowing slow devaluation.

Exports improved with the slow devaluation, but reforms were too gradual.

Government committees (1978 and 1984) called for simplifying the import licensing system. Suggestions included replacing licensing with tariffs, but they lacked urgency.

That's all for today, folks. Next time, we’ll get to the 1980s and the creation of a constituency for reform. Stay tuned.

Lovely paper, once again. A must-read for any Indian with even a slight interest in our economic history.

Anurag—Going back to the old internet

For years, the internet has been evolving in one direction—more interactive, more visual, more complex. Websites became flashy, filled with animations, pop-ups, and algorithmically tailored feeds. But, suddenly, it looks like AI is going do an Uno reverse on it.

I came across an interesting perspective today: AI agents are changing the way we interact with the web, and in the process, they might bring us back to a simpler internet.

Imagine this - instead of clicking through a dozen travel sites to find the best flight, your AI agent just fetches the cheapest, fastest option and literally.. books it! Instead of scrolling through news feeds filled with ads, your AI summarises the top stories you care about. Instead of navigating an e-commerce jungle, your AI simply orders what you need based on past behaviour. No pop-ups. No loading times. No cookie banners.

The AI-enabled online world we’re stepping into could possibly change the fundamentals of how we look at the internet today.

And if that happens, websites could start looking a lot less like glossy magazines and more like how the web began—pure text. This could be optimised not for humans but for AI agents.

And it’s crazy if you think about it. The internet went from simple text pages in the 90s to almost like a cluttered interactive mess. And now, it could just be back to a more minimal, AI-friendly version of itself.

Also, if AI agents become our primary way of interacting with the internet, the role of web developers will change drastically. AI-first development could become the new standard, where businesses focus on optimizing their data for AI rather than humans. This shift might also reduce the power of traditional SEO.

Currently, companies optimise websites to rank on Google, but if AI agents handle search, they’ll pick results based on relevance and accuracy, not just clever keyword stuffing. This could fundamentally change digital marketing altogether.

Kashish - Solution to my post-lunch sleepy problem

Most days after lunch, I’d feel waves of fatigue hit me—like clockwork. My eyelids would get so heavy, I’d almost doze off at my desk. It was annoying. I had plenty of theories about why this was happening, but none of them were right.

Not enough sleep? Couldn’t be. I’m a sleep fiend. I don’t track my sleep obsessively like those Whoop-wearing fanatics, but I make sure to get a solid 7.5 hours every night. It’s not always perfect, but I try. And on the rare days I don’t, I panic—not just because of my gym gains (which, of course, I treat like life and death) but also because I assumed this was the reason for my post-lunch slumps. Except…it wasn’t. Even on days I clocked a full 8 hours, I’d still feel like crashing mid-day.

Sugar crash? Made sense. I eat heavy. Permabulk—whatever that means—is my default mode. My philosophy was simple: eat till you can’t move, then eat some more. It worked wonders for my skinny frame, but it also meant I was shoveling down carbs—rice, rotis, the works. If that wasn’t a recipe for a glucose crash, then what was? But again, that theory fell apart. Even on days when I kept lunch light, I still felt like curling up in my chair and passing out.

Boredom at work? Now, I wouldn’t want my boss to hear this, but I did consider that maybe my work was just too dull, making me feel drowsy. But, obviously, that wasn’t true. I love what I do. 🥰

After cycling through these theories and finding no real explanation, I did what any rational person would do—I stopped treating it as a problem. Classic case of "if I can’t figure it out, it must not be real." Not my brightest moment.

Then, by complete accident, I found the solution.

I’ve been meaning to take supplements more seriously. Until now, Vitamin D3 was the only thing I bothered with. But I’d heard good things about fish oil and figured a multivitamin wouldn’t hurt. No reason not to try, right? Except I kept procrastinating—why? No clue.

Finally, after spending way too much time ChatGPT-ing and consulting a trusted friend, I ordered both.

Day 1: Took them cautiously. Avoided mixing fish oil with milk. Kept the multivitamin away from tea. Played it safe. Mild stomach discomfort? Sure. But I was prepared.

Day 2: Repeated the process, felt fine.

Day 3: Same routine, no issues.

Then I realized something strange. All this while my post-lunch fatigue disappeared.

At first, I thought it was intermittent—maybe just one of those random good-energy days. But the next day? Still no slump. And the next? Same.

Then it hit me.

A couple of months ago, I had a full-body checkup. Everything was normal—because, obviously, I’m built different—but there were some minor deficiencies: Vitamin D (expected), Vitamin B12, and iron. Nothing major. I shrugged it off, thinking I’d fix it "organically" through my diet.

Turns out, I didn’t. Iron deficiency = fatigue. Multivitamin = iron. Fatigue = gone.

It all made sense.

Now, as I type this at 9:10 PM, I’m still buzzing with energy—something that would have been unthinkable before. By now, I’d usually be zoning out, just waiting to crash into bed. What did I learn today? If I’m getting a health checkup, I should actually do something about the results. Took me long enough to figure that out, but hey—better late than never.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.