Bhuvan—Quantifying the damage of trade wars

"All models are wrong, but some are useful."

This banger of a quote is by British statistician George Box, and it's one of my favorites. It's a nice reminder that, try as we might, reality is irreducible and messy. This thought popped into my head as I started reading about Donald Trump—AKA little Donnie—slapping 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico. Poor Canada. This is what their niceness begat.

We hate uncertainty, and the world is uncertain. And therein lies the horribleness of life. — Swami Bhuvan.

Banger, ain't it?

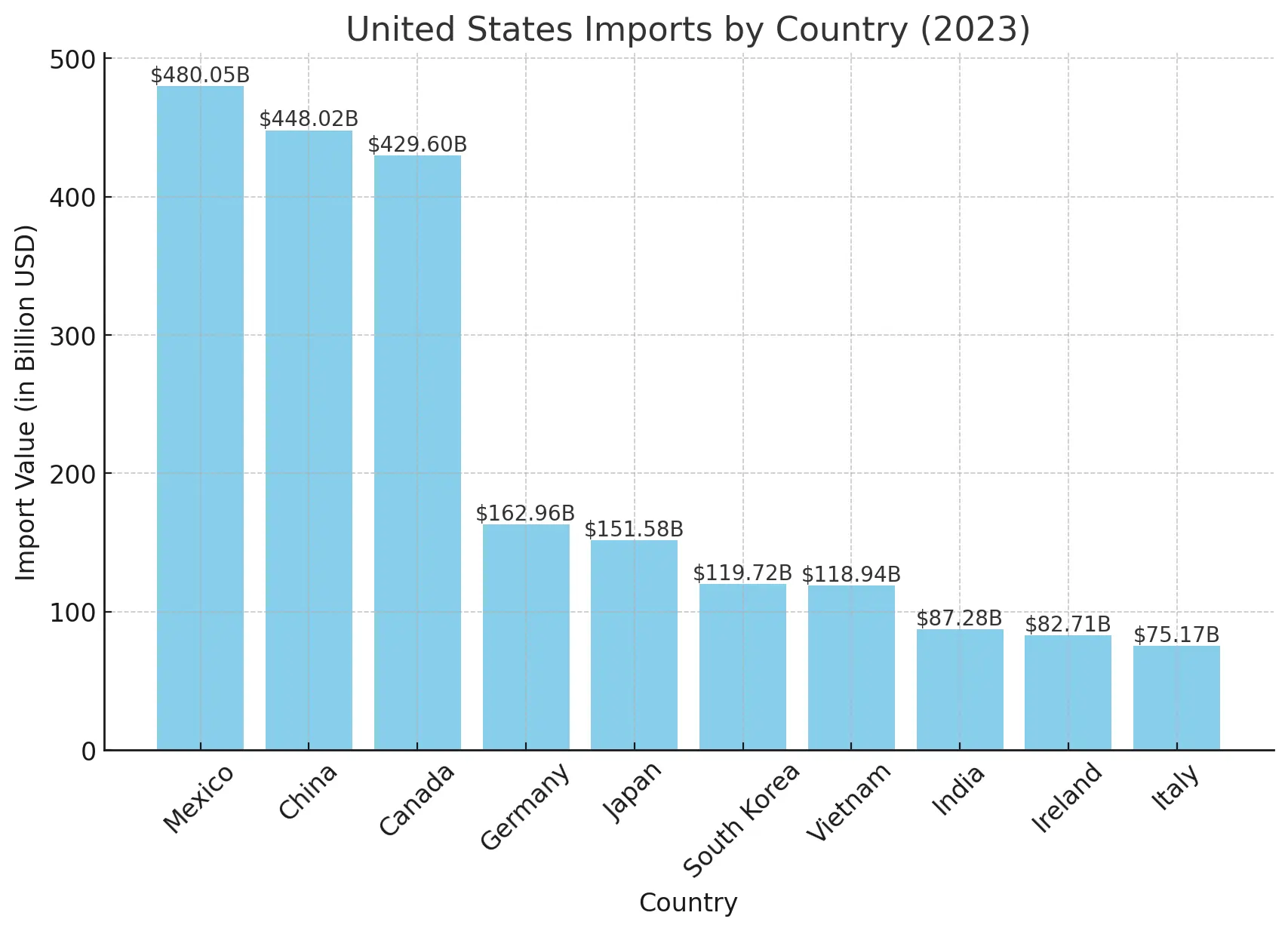

Ok, banging aside, the tariff gun has been fired, and tariffs are no joke. Both Canada and Mexico have imposed retaliatory tariffs, albeit weak ones. One way to think about this is through a dumb game theory framework. The ideal state—where no one imposes tariffs—has been tossed into the toilet, shat upon, and flushed.

Now, we are in the tat stage of tit, and all sides are being forced towards a suboptimal Nash equilibrium that leaves everyone worse off.

A dumb model of the payoffs

- If no country imposes tariffs, everyone benefits from free trade. This is the nice equilibrium that finance people fantasize about. Yes, this is a kink for finance and trade economists. #SedLife

- If one country imposes tariffs and the other doesn't retaliate, the imposing country gains a short-term advantage, but the others suffer. The kink has now worn off. It's econ BDSM now.

- If all countries impose tariffs, everybody collectively faces higher costs and reduced trade. It's a lose-lose scenario.

It goes without saying that this is a vastly oversimplified model that ignores the nuances of trade, but I still think it's a useful frame.

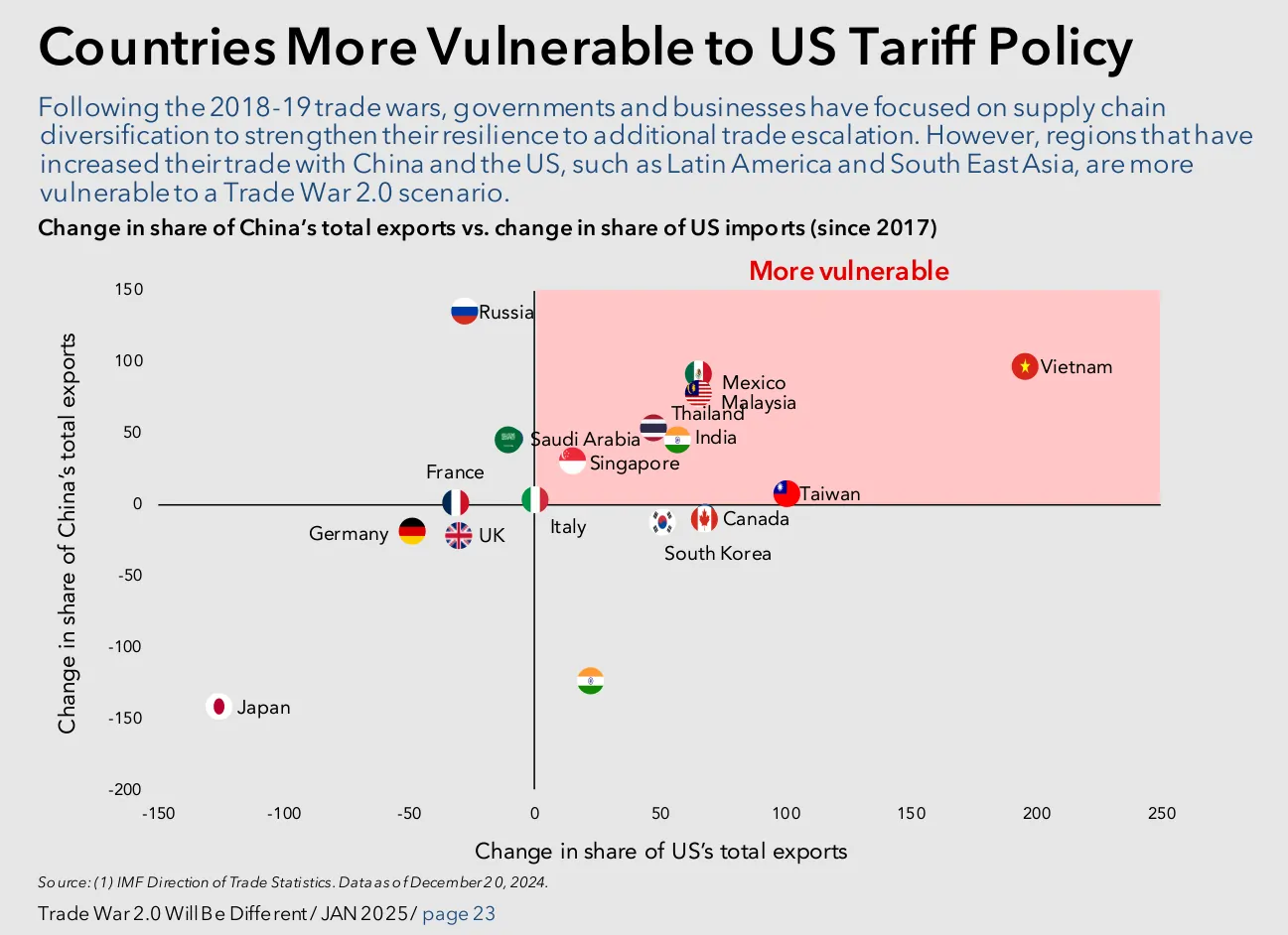

One can no longer discount the possibility that Trump won't impose tariffs on other countries.

Now that the leader the white people elected with great pomp and circumstance has decided to do dumb things that are really well thought out, verging on scientific stupidity, we must understand how bad this can get for the rest of us brown people. The answer, of course, is we can't know. However, as good ol’ George Box said, we can learn from some wrong but useful models.

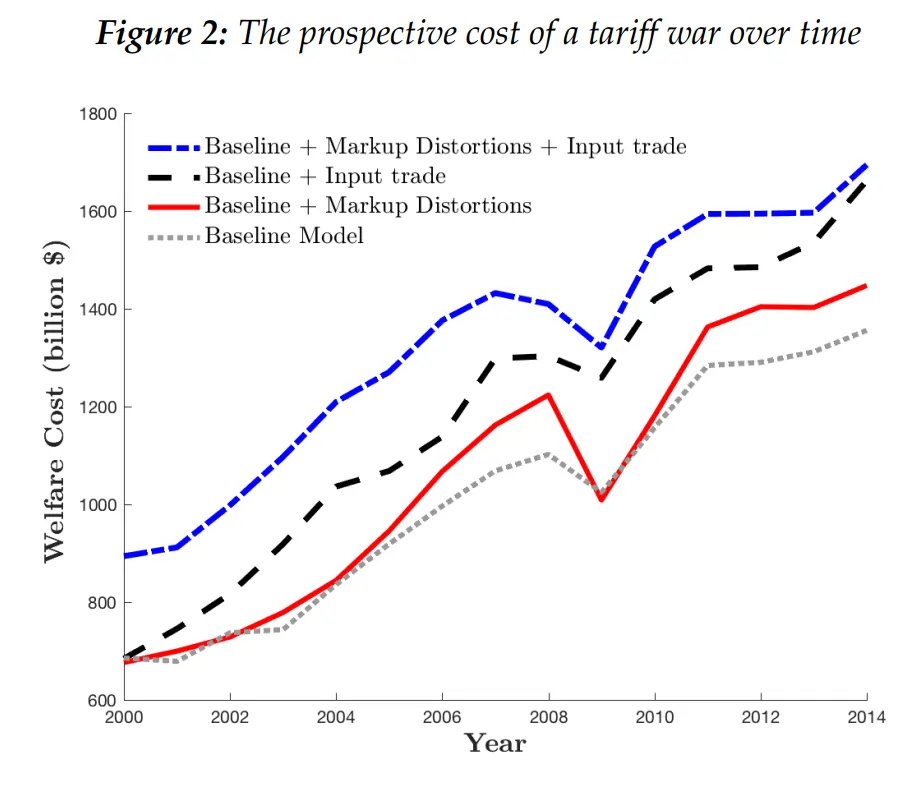

With that in mind, I read this fascinating paper by Ahmad Lashkaripour of Indiana University, in which he tries to quantify just how bad lil Donnie's big trade war can get.

Here are some depressing numbers:

- A global tariff war can reduce the average country's GDP by 2.8%.

- In 2014, the expected cost of a global tariff war was $1.7 trillion—the equivalent of erasing South Korea's GDP from the global economy.

- Smaller economies like Estonia, Latvia, and Bulgaria will be the biggest casualties because of their increasing reliance on intermediate inputs.

- Trade wars amplify pre-existing market distortions and inflict bigger losses than the counterfactual.

In a tweet summarizing his paper, Ahmad wrote:

"TLDR: All countries ultimately lose. While the overall impact isn’t catastrophic for larger economies like the US, it’ll be devastating for small countries."

In a full-blown tariff war, every major country loses—even the US is not spared. However, the losses will be much larger for smaller countries that rely more heavily on imports.

A fork in the road

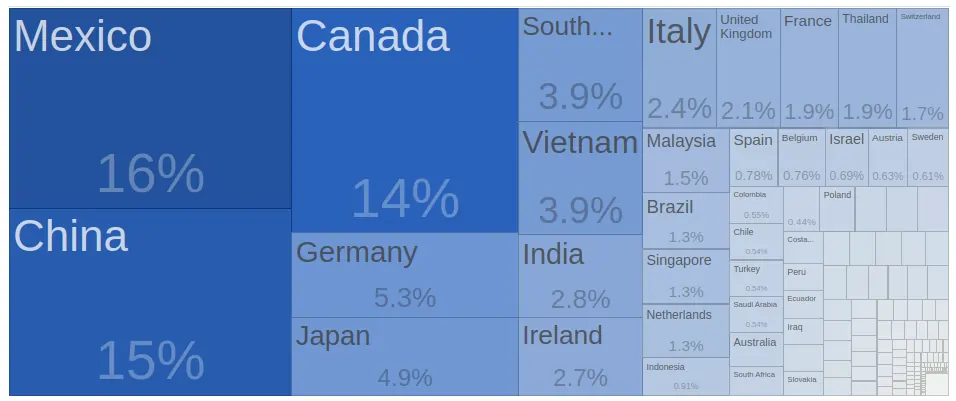

The US has just imposed sweeping tariffs on almost $1.4 trillion worth of imports from its three largest trading partners. This level of escalation is unprecedented in recent history.

During Trump's first term, tariffs were rolled out over months, but this time, it's happening in a matter of weeks.

No matter how you slice it, this feels like an important moment—but in a dangerous way. I don't have a clear articulation, but the sheer disregard for norms, values, rules, and unsaid agreements that have held the world together like duct tape doesn't bode well for the future.

This isn’t to say that all those shibboleths were gospel, but surely, this midwit philistine revolution can't be the path to reform?

Or maybe, this is exactly what the world needed to shake it out of its complacency?

Is this a fork in the road, or just history playing out?

This is a question I wish to explore more in the coming months.

Krishna—Quick look at the history of India’s nuclear space

I had watched a few episodes of the critically acclaimed Chernobyl series some time ago, but I didn’t remember much of it—until today. While reading about a proposed amendment to India's Atomic Energy Act in the latest Budget speech. But the thing is, I literally had no idea all the context related to India’s nuclear history.

In India, private players are not allowed to build or operate nuclear power reactors. Nor can they independently source nuclear materials from other countries. This policy dates back to the Atomic Energy Act of 1962, which gives the central government a monopoly over nuclear energy.

India had the opportunity to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), an international agreement designed to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. However, India chose not to sign the treaty. Why? Because signing the NPT would have meant accepting the nuclear status quo: the five officially recognized nuclear powers (the US, Russia, China, the UK, and France) would have controlled global nuclear technology and material supplies. India, concerned about its strategic security—especially due to its tense relationship with Pakistan—did not want to depend on these countries and lose its ability to develop nuclear weapons or reactors independently.

This decision strained India's relationship with the US for years, as the NPT was heavily backed by Washington. However, in 2006, things began to change. The India-US Civil Nuclear Agreement (also called the 123 Agreement) allowed India to import nuclear fuel and technology from other countries for civilian nuclear power projects—without joining the NPT. This agreement opened doors for foreign companies eager to collaborate with India’s nuclear energy sector.

But then things took a turn. In 2010, India passed the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLND), which introduced a unique provision: if a nuclear accident were to occur (like Chernobyl or Fukushima), the operator (usually a state-owned entity like NPCIL) could claim compensation from suppliers (foreign or domestic). This was highly unusual. In most countries, nuclear operators bear full responsibility for accidents, not suppliers.

The problem with this clause was obvious. Suppliers—who merely provide materials, equipment, or components—had no control over reactor operations. Yet the law made them potentially liable for accidents. Unsurprisingly, this clause triggered strong pushback from foreign nuclear companies like Westinghouse and Areva. Many of them backed out of Indian projects due to concerns about unlimited liability risks. Domestic suppliers were also hesitant to get involved.

Fast forward to the present. In the new Budget, the Finance Minister announced that the government plans to amend the Civil Liability Act, specifically to ease supplier liability provisions. This could be a game-changer. India has committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070, and nuclear energy is critical to meeting this target. By addressing supplier concerns, India hopes to attract foreign and domestic investment in its nuclear energy sector—something that’s long overdue.

Kashish—South Indians should have 16 kids!

“Demography is destiny.”

I came across this quote while reading a blog by either the World Bank or the IMF. The author was making a simple argument—favorable demographics can drive economic growth. The logic? More people entering the workforce means higher output, and even if productivity stays the same, GDP goes up.

Here’s the basic math behind it:

GDP = Labour productivity × Number of Workers

That’s the oversimplified explanation of why demography plays a crucial role in economic growth. But there’s also a political angle to it—one that has South Indian states particularly worried.

The Delimitation Exercise and Why It Matters

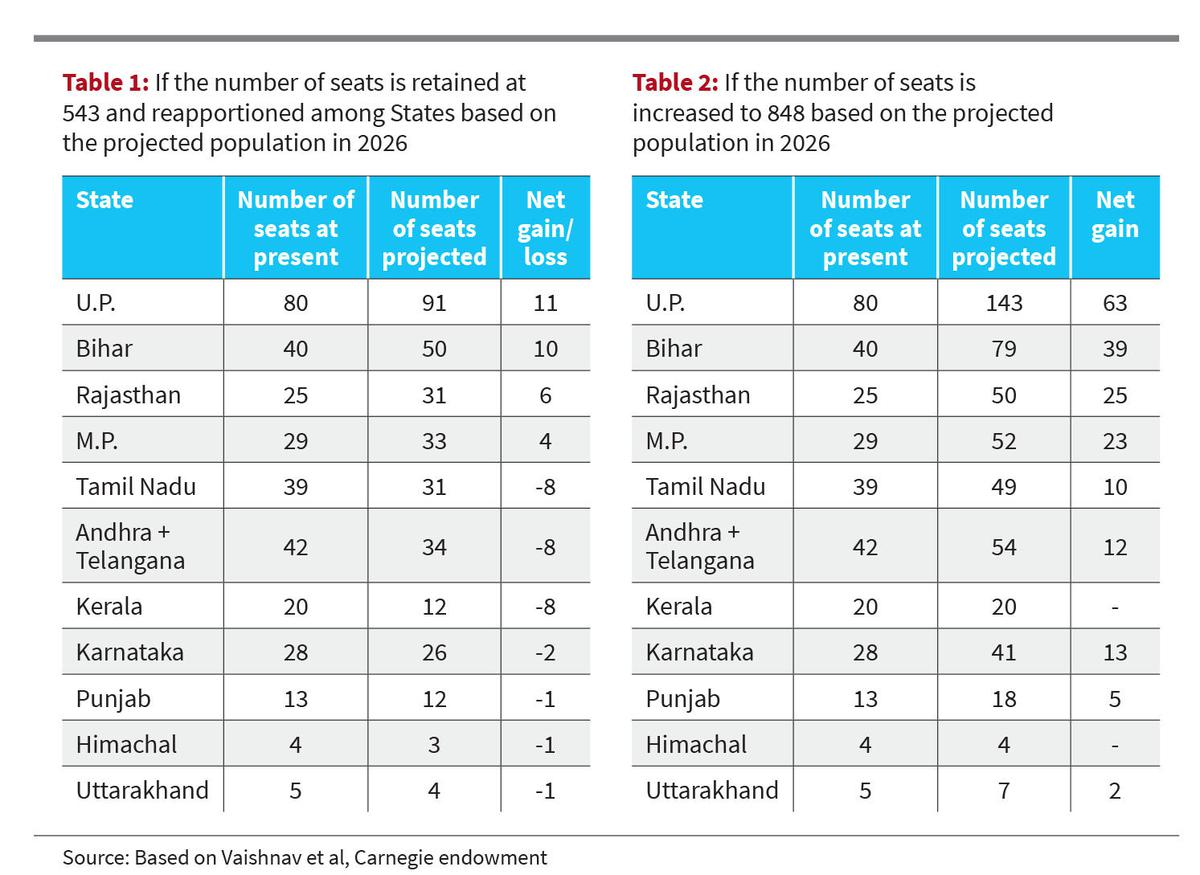

In 2026, India is set to undertake a delimitation exercise.

Delimitation means the process of fixing the number of seats and boundaries of territorial constituencies in each State for the Lok Sabha and Legislative assemblies.

Now, democracy is based on the principle of one person, one vote, one value. That means a state with a larger population should ideally have more seats in the Lok Sabha. But here’s the twist—this hasn’t been the case for a while.

However, it [number of seats] has been frozen as per the 1971 Census in order to encourage population control measures so that States with higher population growth do not end up having higher number of seats. This was done through the 42nd Amendment Act till the year 2000 and was extended by the 84th Amendment Act till 2026. Hence, the population based on which the number of seats is allocated refers to the population as per the 1971 Census.

But once this freeze lifts, the number of seats will be recalculated based on the first Census after 2026. And that’s where things get tricky—states that have seen higher population growth since 1971 will gain more seats (and more political influence), while those with lower growth will see their representation shrink.

Source: The Hindu

And guess which states have managed to control their population growth the most? The South.

Why South Indian States Are Worried

South Indian states have been remarkably successful in bringing down their fertility rates. The fertility rate in these states has dropped to 1.6, well below the national average of 2.1. While this has been great for social development and resource management, it might now work against them politically.

Tamil Nadu, for example, has used some pretty creative policies over the years to encourage smaller families. At one point, the state even barred people with more than two children from contesting local elections (a law that has since been repealed).

Now, realizing that low fertility might cost them political influence, the Tamil Nadu government is considering reversing its stance—potentially incentivizing larger families instead. There’s even talk of introducing a law that would allow only those with more than two children to contest local body elections!

And then there’s MK Stalin, Tamil Nadu’s Chief Minister, who recently made a bold (and rather dramatic) statement—urging people to have 16 children!

Of course, he was joking (hopefully), but the underlying concern is real. If South Indian states don’t act, they might find themselves with less political power in the years ahead, while states with higher fertility rates gain more influence in national policymaking

So that’s what I learnt today. Demography is Destiny – just doesn't apply to economics, it applies to polity too. Destiny of southern states in India’s case.

Tharun—Zuck wants to replace smartphones

Zuck is making a $100 billion bet on the future of technology. Meta (formerly Facebook) is projected to spend this amount on Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) by 2025. This investment is on par with Amazon's Alexa or Google's push into cloud computing. But why is Zuck trying so hard?

He sees VR and AR as the next major computing platform, potentially replacing our smartphones altogether. If this works out in Zuck's favour, it will give him independence. How? If they create their own ecosystem with VR and AR, they could break free from Apple and Google's ecosystem of apps and products.

And things are somewhat looking good for Zuck. Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses sold a million units last year, and a new version with a mini display is coming. Imagine seeing navigation instructions floating before your eyes or getting real-time translation as someone speaks to you in another language. Meanwhile, they have sold 30 million Quest VR headsets, but they are still in search of a game-changing app that could increase adoption.

I think the applications of AR and VR extend far beyond just gaming and social media. Surgeons could use AR overlays to visualise procedures in 3D. Students could virtually walk through historical sites. Imagine students in class, learning about the Indus Valley not just through photos but by virtually walking through it. You can virtually take your meetings, sitting with your colleagues, while working from home. The applications are endless, and if Zuck is able to pull this off, this will change how humans work, learn, and interact.

But of course, there are serious challenges. AR/VR needs to become more affordable and compelling for average consumers. Meta also needs to address privacy concerns and build trust, particularly given their complicated history with user data. And they are not alone in this race either—Apple, Google, and Microsoft are all developing their own AR and VR solutions.

Meta can afford this ambitious bet for now, thanks to their profitable advertising business. But what Zuck has set out to achieve, replacing smartphones, is a massive bet that he is taking, and only time will tell how this pans out. But it will be fun to see how this all plays out.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.