Pranav—The Rules-Based Economic Order

We recently did a story on tariffs on the Markets channel. And while we covered a lot of ground — more than most 'pundits,' I reckon — there are still things we left unsaid.

See, when you're trying to cover the news, everything is monumental — but not equally so. Any given thread you look at has the potential to change lives. But not an equal number of them. Some pieces of news change a few dozen lives, some thousands of lives, some lakhs, and a few rare ones change billions. These are profoundly different in scale, but it's hard to convey the difference in words. What lies beyond life-changing news? Kilo-life-changing news? Mega-life-changing news? How do you convey the scale of importance of any story when every damn story is more important than anything you've seen in your everyday life?

Anyway, back to the point. If the Trump tariffs are what they seem to be — not an aberration, but a fork in the road — then we're staring at something at the very highest level of abnormal. We’re looking at a story that might shake billions of lives.

We might just be looking at the final nail in the coffin of the "rules-based economic order." And if that’s the case, we should all know what we’re on the verge of losing. These are my loose thoughts on the matter, as I read whatever I can find. You’ll soon see a prettier, better-constructed version of this on the Markets channel.

The WTO is Dead

Let’s face it. The WTO is dead. Trump killed its appellate body back in 2019, and Biden let it stay dead. We’re only starting to see the fallout now.

The WTO was a naive, utopian idea — one that's enormously cute, in hindsight — that a global body could censure countries into behaving fairly with each other, even when they had all sorts of economic incentives to do otherwise.

It wasn’t really backed by anything — other than a vague idea that other countries would sanction you if you didn’t play ball. But of course, that wouldn’t work automatically. Sanctions are complicated political instruments, and if you’re sufficiently powerful, you can just stare others down.

What’s incredible, though, is that it worked. For a while, we all pretended like the WTO really did have any authority. Why? Because all the international big boys — the United States, Europe, Canada — acted as though it did.

The Rules-Based Economic Order and Certainty in Trade

There's perhaps one thing the 'rules-based economic order' allowed for, and that’s certainty in foreign trade.

This is, in econ-speak, a public good. Society benefits immensely if businesses know how to structure their operations to keep things moving smoothly. And yet, no single individual (or country, in our context) benefits from paying to keep such a situation alive.

The United States, to a great extent (despite its many flaws and underhanded dealings), stepped into that role. It was the backstop for huge multilateral projects trying to create that environment of certainty. Because the U.S. stepped up, we had a brief era where people around the world were willing to transact with each other.

If the United States becomes a force for economic chaos rather than order, that's a horrible loss to the world. Without this public good of international certainty, global trade becomes infinitely riskier. It won’t die overnight, but it’ll suffer in a way the vast majority of us have never seen.

China’s Role in the Fallout

A lot of the blame for this fallout lies at the feet of China.

China has never respected the existence of an international economic order. It has gamed the system wherever it could.

It manipulated its exchange rate, provided massive domestic subsidies, picked winners, ignored treaties, engaged in gunboat diplomacy, and dumped goods. This is a massive simplification, but broadly true. And what's worse? It worked. China became a global superpower without investing in the system that permitted its supremacy.

The United States is now caught in a prisoner’s dilemma. The system worked when the U.S. was the sole global superpower. Now that there are two, it only works if both cooperate. Otherwise, the cooperative party gets exploited.

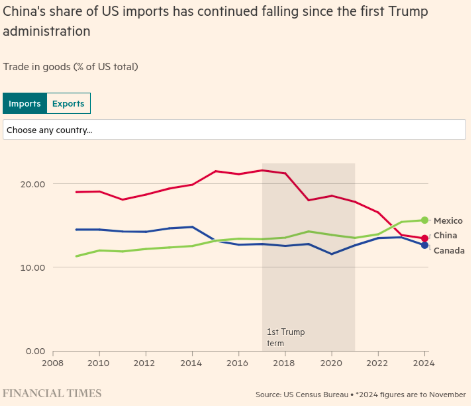

Playing hard-ball with China seemed effective for a time, but it may not work anymore. Price-sensitive imports have already shifted away from China. However, China’s trade surpluses have only risen, recently hitting a trillion dollars.

The Need for International Cooperation

The world requires more international economic cooperation, not less.

Adam Tooze points out that Africa will soon have more working-age people than the entire developed world. These people could form a new engine for global growth, similar to China post-Deng's reforms or India after 1991.

However, this requires global financial institutions better than the IMF and the World Bank. Instead of progress, we're seeing backsliding.

A Cuckoo Theory

Here’s a cuckoo theory, but one that Trump's circle might actually buy into:

Source: Ham and Cheese on X (formerly Twitter)

Trump’s strategy may involve de-dollarising the world, making it harder for others to buy dollar-denominated reserves, and pushing for a new economic order that removes America's exchange-rate disadvantages.

It's audacious but risky. The plan has a million ways to go wrong and only a narrow path to success.

A Global Economic Leadership Vacuum

America could not have backstopped the rules-based economic order forever. As it steps back, there is an opportunity for others to fill the void.

- Nations still demand economic stewardship, and some will align with whoever can lead them to development and self-sufficiency. We are witnessing a vacuum in global economic leadership.

Nature abhors a vacuum.

That's all for today, folks. I’ll probably follow this up with more one of these days.

Source: Ham and Cheese on X (formerly Twitter)

Tharun—Money can’t buy happiness, but happiness can help save more money

We've all heard that money can't buy happiness, but happiness can buy money, and cried a little every time we heard it. But it turns out there could be some truth to this: being happy - or more specifically, being optimistic - might actually help you save more money, according to research from the American Psychological Association.

The research team, led by Dr. Joe Gladstone from the University of Colorado Boulder, conducted an extensive study across multiple countries. They analysed data from over 140,000 participants in the U.S., U.K., and 14 European countries. And they found that people who maintained an optimistic outlook about their future consistently managed to save more money.

How much more? For households with average savings of $8,000, those with higher optimism saved an additional $1,352 on average. That's a significant difference, especially considering that this held true even after accounting for factors like age, income, relationship status, and personality traits.

And crazily enough, it turns out optimism is an even stronger factor in saving behaviour than financial literacy or risk tolerance. All those complex financial concepts we struggle to understand might be less important than simply maintaining hope for the future.

This effect was particularly strong among people with lower incomes. As Dr. Gladstone explains, this makes sense. When you're living pay cheque to pay cheque, saving money can feel pointless. But having an optimistic outlook can provide that extra push needed to set aside even small amounts of money, despite current challenges.

I now know whom to blame for my poor financial situation. I need to go shout at my financial advisor for not sending me Sandeep Maheshwari videos and helping me build an optimistic mindset.

Bhuvan—China vs the world.

The one thing that has been bothering me for a while is the growing intensity of anti-China sentiment in the West. In the last ten-odd years, China has quickly become the scapegoat for all ills that ail the West—from economic malaise and inequality to drug epidemics, crime, and the fraying of the social compact. China has become everyone's go-to boogeyman.

To politicians, the "China is evil" narrative is a gift that keeps on giving and has bestowed the world with the likes of Trump among others. There's a saying in the stock market: "Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM." In politics, this pithy remark can be rephrased to say, "You can't go wrong when blaming China."

I was recently listening to an interview with prominent historian and public intellectual Niall Ferguson that brought this issue to mind.

In the interview, Ferguson explicitly uses adversarial labels when discussing China, and frankly, this entire line of thinking is starting to concern me. It feels like the US, if not the collective West, has made peace with the fact that a major conflict with China is inevitable and is sleepwalking into it.

Two moments from the interview stood out to me. Here are the transcript snippets:

"In many ways that was the interwar period - the interwar period between Cold War I, when the Soviet Union was the major threat, and Cold War II, when China is the major threat. And you can't expect to carry on playing the game that you've played when China is not only a major trading partner, a major destination for Australian exports, but is also the principal threat to your national security."

"China was not pursuing a policy of free trade. On the contrary, because it was violating its World Trade Organization obligations, it was in breach of the rules of free trade. China had a Made in China 2025 strategy which was to subsidize domestic manufacturing. It was engaging in wholesale intellectual property rights theft. It was time to turn the tables on China. That's not a violation of Adam Smith's principles - that's smart bargaining in an international system in which one side is not playing by the rules of free trade. So I think Trump did the right thing, and the tariffs, interestingly enough, were highly disruptive of China's economic game plan, really derailed China's growth without costing American consumers the amounts of money that Trump's critics kept saying they were."

The impact of China on Western deindustrialization is a complex issue. It's been two decades since China joined the WTO, and there's still no agreement among experts, with a rich strand of literature on the topic.

I wanted to share this because I intend to explore this topic in depth, and I needed this space to think about the insanely complicated issue that is China vs. the West.

Krishna—What the hell is Sino-British?

I was doing some research for Who Said What and stumbled across something called the Sino-British Joint Declaration. Here’s the gist.

Hong Kong had been part of Britain’s colony since the 1840s, after Britain won the First Opium War (I need to dig into that more). The British had leased a large portion of Hong Kong’s land—known as the New Territories—from China. That lease was set to expire in 1997.

So, in 1984, Britain and China signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The UK agreed to hand Hong Kong back to China on July 1, 1997. But there was a catch: China promised that for 50 years (until 2047), Hong Kong would operate under a system called "one country, two systems."

Here’s what that meant:

- Hong Kong would keep its capitalist economy and legal system.

- It would enjoy a high degree of autonomy, essentially running its own affairs.

But in recent years, China has been accused of tightening its control over Hong Kong, especially through laws that limit protests and political freedoms. Critics argue that China isn’t honoring its promise under the agreement.

This is just a surface-level overview—I'm still diving deeper into it. If you’re curious, here’s the article where I first came across the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

Anurag—Are we close to AGI?

Recently, I came across an interesting test designed specifically to measure how close we are to AGI or Artificial General Intelligence.

For years, AI has been evaluated using standard exams like math problems, logic puzzles, and even PhD-level questions. But the problem is, AI keeps getting better at them. So, researchers have now developed a new, much tougher test to truly gauge AI’s intelligence.

It’s called Humanity’s Last Exam, and it’s designed to push AI to its limits. This is a crowdsourced test, meaning some of the world’s smartest minds - college professors, mathematicians, physicists, and more - have contributed questions to make it as difficult as possible. And these aren’t just multiple-choice questions you can guess your way through. They demand deep reasoning, problem-solving, and expertise across diverse subjects.

Even creating these questions isn’t easy. According to The New York Times, researchers who submitted top-quality questions were paid between $500 and $5,000 per question.

Now, why does this matter? Because if AI can consistently solve problems that require expert-level thinking, we might be closer to AGI than we realize. And AGI isn’t just about answering questions - it’s about reasoning, problem-solving, and thinking like a human. This test might be the closest thing we have to measuring how near we are to that future.

So far, six major AI models have taken the test, including Google’s Gemini 1.5 and Anthropic’s Claude 3.5. The highest score so far has just been 8.3%. In comparison, a top human expert would score nearly 100%.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.