Krishna—Who’s the next Hindenburg?

So, Hindenburg Research, the infamous short seller that brought chaos to markets with exposés on companies like Adani and Nikola, shut shop a few weeks back. Naturally, when Financial Times recently wrote a piece on who might take over Hindenburg’s mantle, I had to check it out. Who wouldn’t want to know who the next villain—or hero, depending on your stance—of the markets will be?

Here’s something interesting that stuck with me:

“Usually, when people exit the short-selling business, it’s because they’ve faced major failures or reversals of fortune,” said Carson Block of Muddy Waters. “In Nate’s case, he’s going out on top.”.

I didn’t completely realise that the landscape for activist short sellers is tough.

Sued by company executives, shunned by banks who are afraid of jeopardising client relationships and investigated by regulators, activist short selling can take a toll on its practitioners.

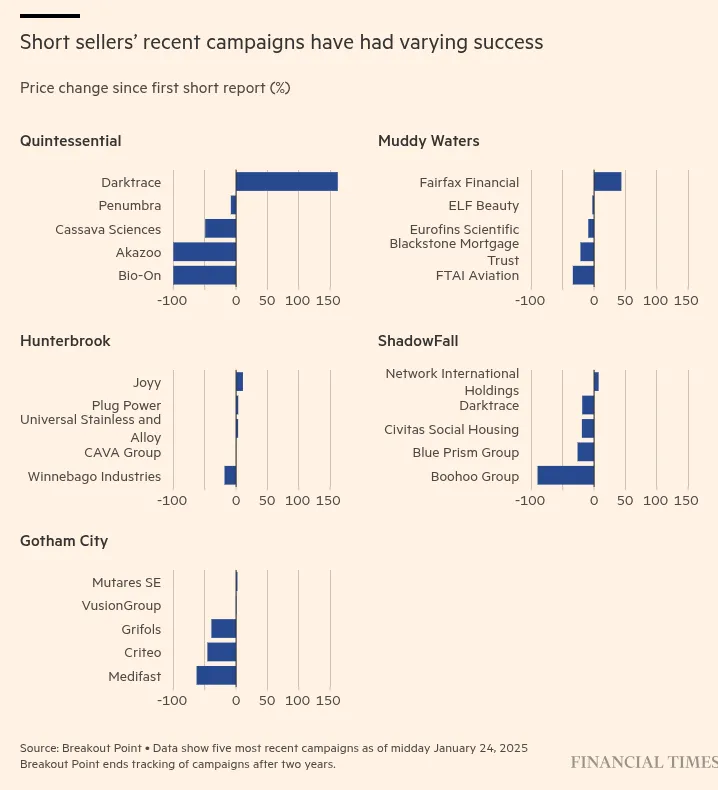

Here's a breakdown of the contenders FT named as the next big short sellers:

- Muddy Waters (Carson Block): The best-known name now. Block made waves in 2011 by exposing fraud at the Chinese company Sino-Forest, leading to its bankruptcy and wiping out $460 million from a billionaire’s fund. Since then, Muddy Waters has targeted both Chinese and Western companies.

- ShadowFall (Matthew Earl): Earl began his career as a bank analyst but rose to fame by anonymously exposing fraud at Germany’s Wirecard under the pseudonym "Zatarra Research." Wirecard retaliated with legal threats and even hired investigators to harass him. Today, his hedge fund, ShadowFall, focuses on overvalued European companies but no longer publishes public reports.

- Gotham City Research (Dan Yu) & General Industrial Partners (Cyrus De Weck): Their joint venture splits responsibilities between publishing reports and managing a $70 million hedge fund.

- Quintessential (Gabriel Grego): Known for its high hit rate, Quintessential operates like a conventional hedge fund but has a reputation for publishing detailed reports on frauds.

- Hunterbrook (Nathaniel Brooks Horwitz & Sam Koppelman): A newer player blending investigative journalism with hedge fund investing. Hunterbrook's newsroom publishes corporate exposés using public information only, to stay clear of securities laws.

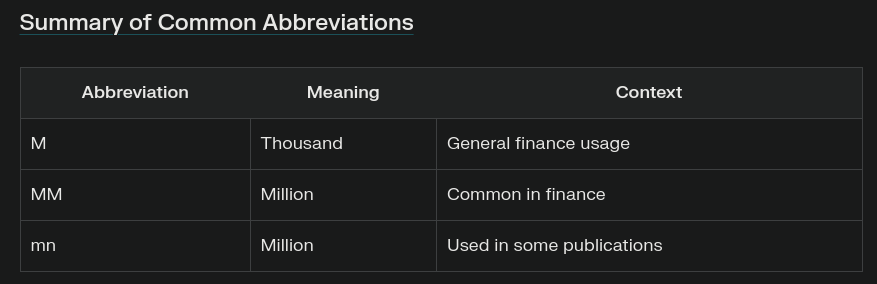

Anurag— What’s MM?

We had an interesting discussion in the office today. One of my colleagues was going through a company’s quarterly report and found a figure “12 mm”, which he couldn’t make sense of.

Million? Milimetre? Something else? None of us knew for sure.

I browsed the internet a bit and figured that “mm” is used interchangeably with mn to denote million. Infact, according to what perplexity says, mm is more commonly used in finance than mn (I don’t quite trust this claim, but let’s go with it for now).

The logic is interesting:

M is the Roman numeral used to denote 1000. MM, therefore, is M multiplied by M, which is 10001000 or 1 million.*

Therefore, MMM, by the same logic, is 1 billion. This is how it all looks as per Perplexity AI.

While this may not be a detailed post like usual, I personally found this interesting. I’m sure most of y’all reading this didn’t know this either.

Bhuvan—Industrial policy is sexy again

Industrial policy has never been this sexy in decades. In the post-COVID era, "self-sufficiency," "self-reliance," and "national security" have become buzz words. Industrial policy is a broad and somewhat amorphous term and no two people mean the same thing. But in the broadest sense, it refers to government targeted interventions and actions to shape the outcomes of a sector or industry.

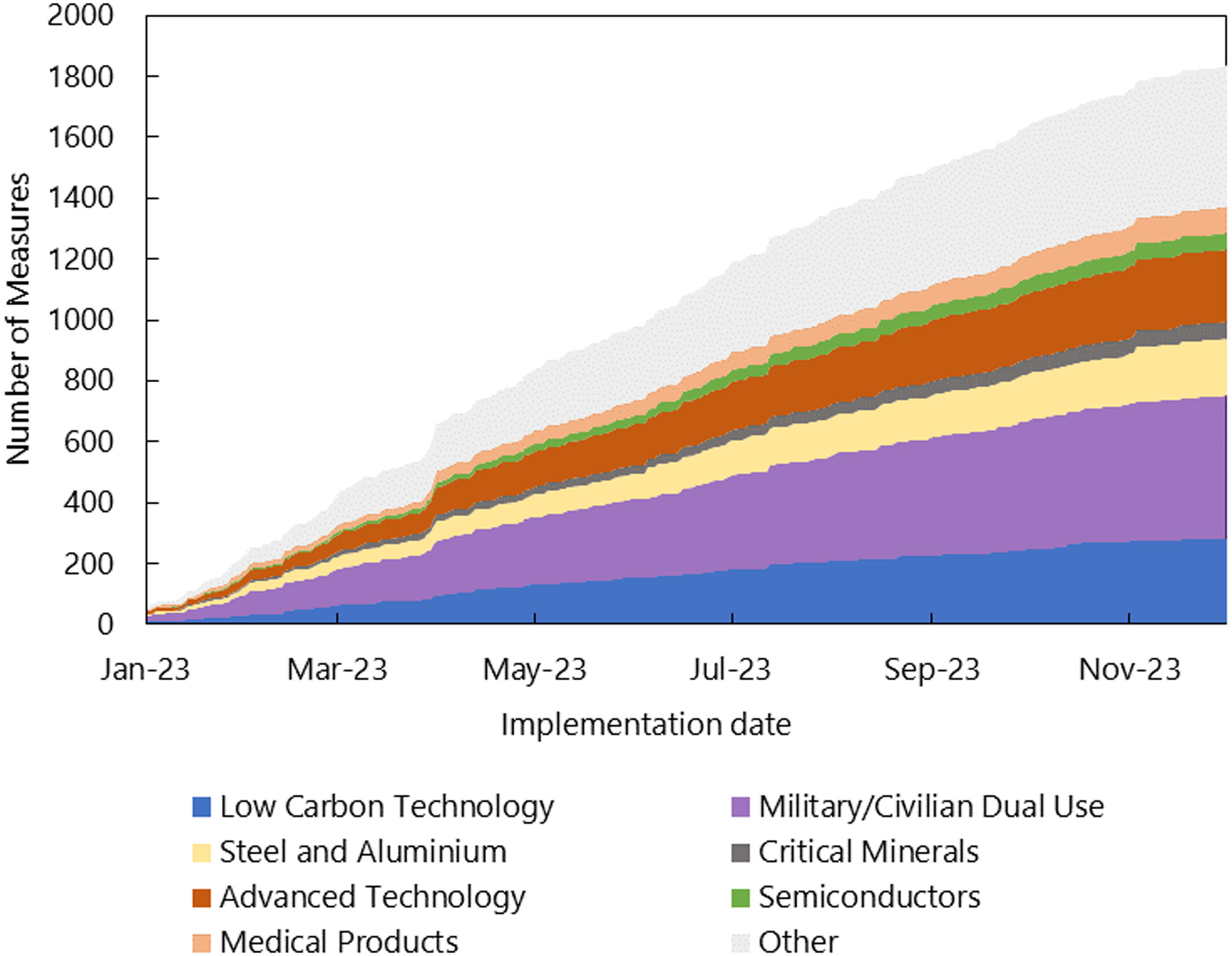

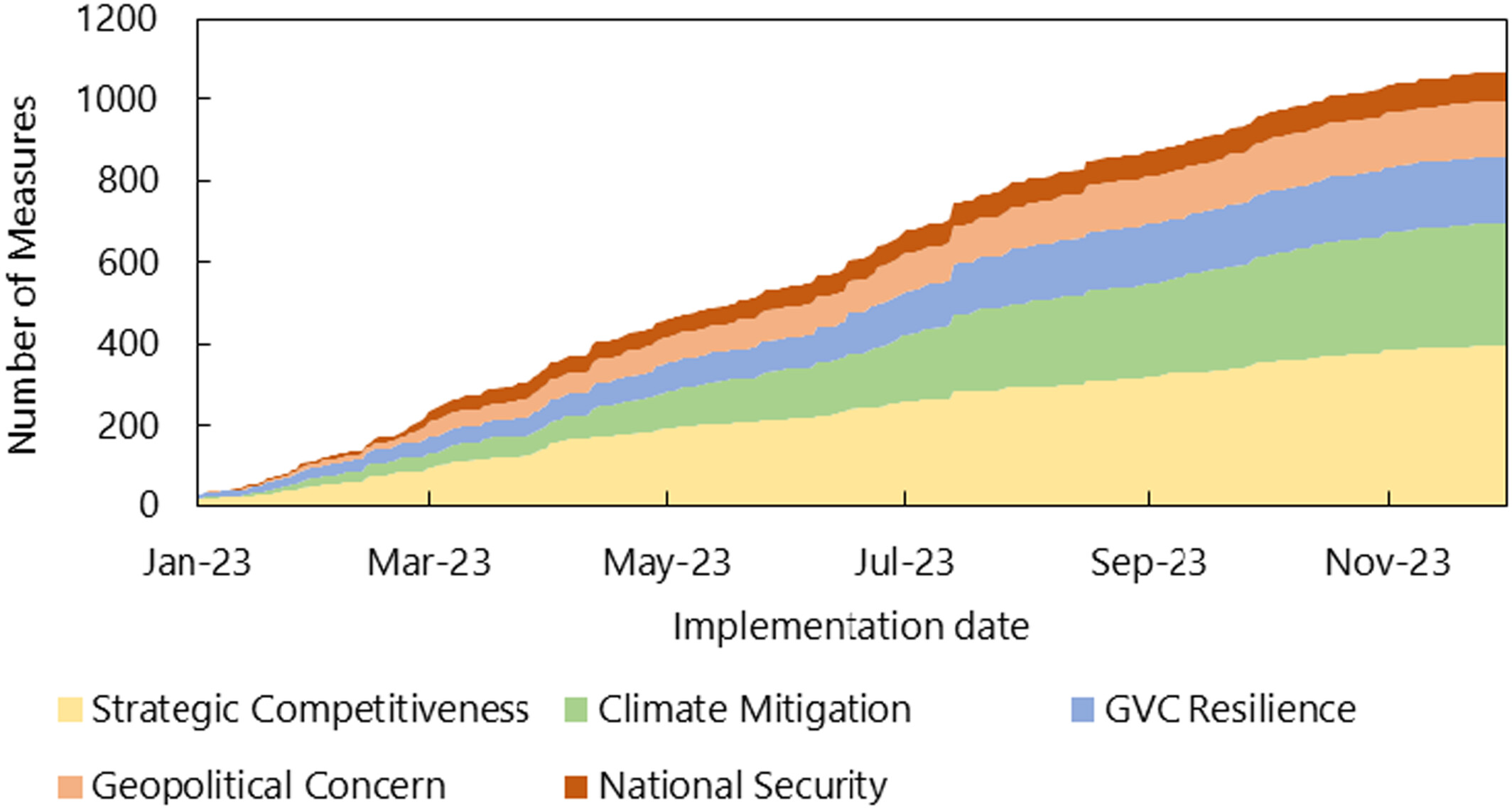

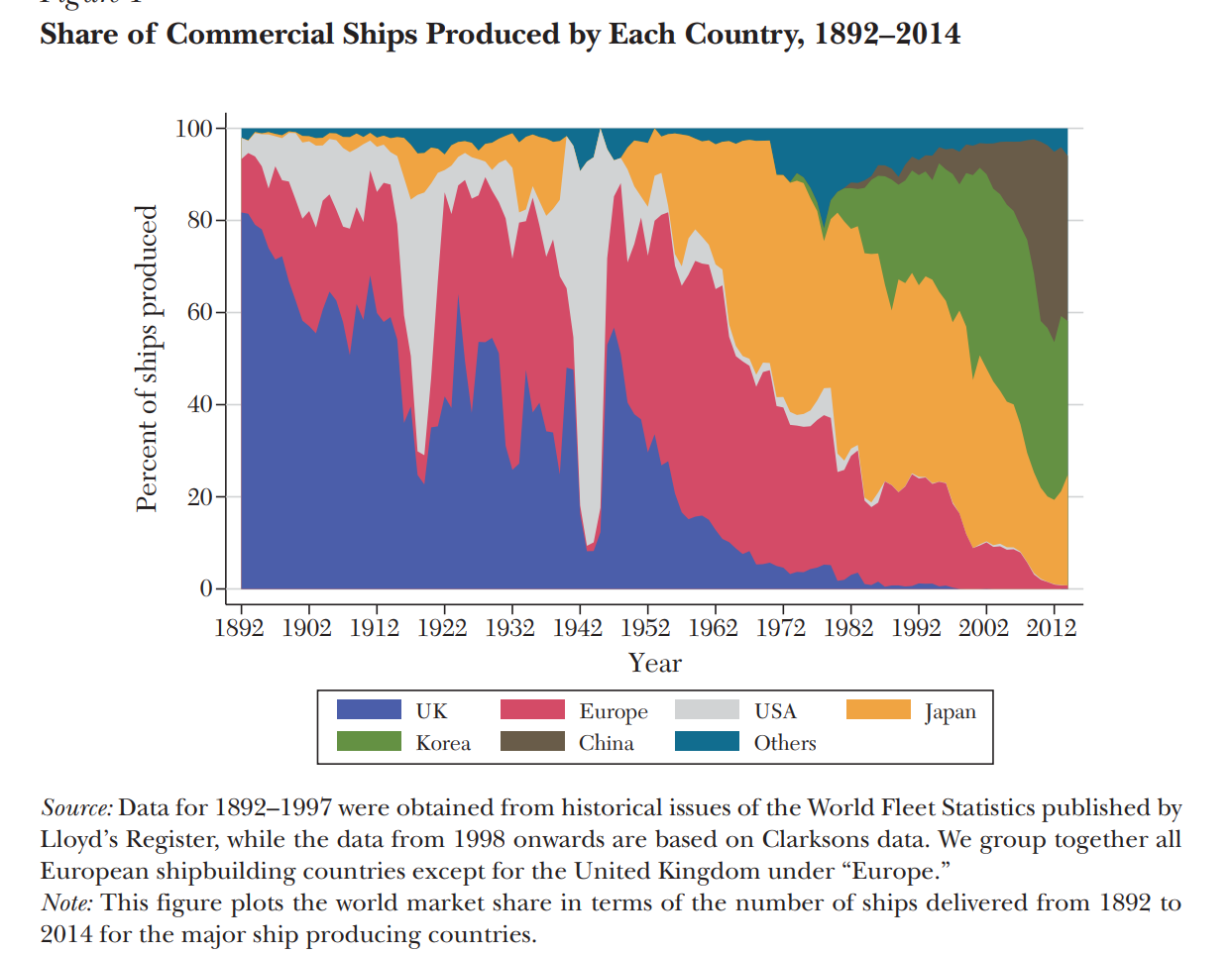

Just take a look at these two charts from this paper:

One of the most recent example of industrial policy is the CHIPS Act by the US to boost manufacturing of semiconductors in the US. Governments enact industrial policy using a range of measures including subsidies, preferential loans, cheap access to land, regulatory relaxations, guarantees etc.

A few reasons for the resurgence of industrial policy are the massive supply chain shocks in the wake of the pandemic, return of large scale wars, increasing geopolitical fragmentation and the end of the fraying of the so-called "rules-based" international order that underpinned much of the post-WWII period. It's an era of "enlightened selfishness."

Industrial policy involves funneling massive sums of money to change the outcomes of industries. Although it's motivated by domestic imperatives, industrial policies can lead to market distortions both domestically and internationally. Depending on the size of the intervention, the second order effects can be massive as we are seeing it with the case of semiconductors and the chip war between China and the United States.

The reason why I am writing about industrial policy is because I read this fascinating paper on Chinese industrial policy targeting its shipbuilding industry. Throughout history the shipbuilding industry has always been a focus of countries due to a variety of reasons such as:

- The links between trade, shipping, and shipbuilding. Over 80% of all trade travels on the oceans

- Industrialization as strategy for growth and employment. Exports are often a byproduct of focus on building industrial capacity and exporting requires ships

- National security and military considerations, especially in wartime

Historical Context

The paper begins with some fascinating history.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries the United Kingdom was the leading shipbuilder thanks to its vast industrial base, dominant role in global trade, overseas colonies, and abundant access to iron and steel. Over the course of the early 20th century UK shipbuilding declined as they struggled to transition craft-based shipbuilding approach to the more capital-intensive industrial production of ships.

Japan took over UK's place as the leader in shipbuilding after World War II. It implemented a series of national programs to build up its shipbuilding industry along with rebuilding its decimated industrial base. Japan became the world's leading shipbuilder in quick order. In 1949, Japan's market share in shipbuilding was 4.7% and by 1970 it had increased to 48%.

Starting in the 1980s, Japanese shipbuilders were being overtaken by South Korean shipbuilding companies as it embarked on its own program of industrialization. Much like Japan, South Korea considered shipbuilding a national priority and provided support in multiple ways like low-interest loans, debt guarantees and so on.

In the 1970s, South Korea's market share of shipbuilding was less than 1% but by 1995, it had grown to 28%. Much of the share came from the ground ceded by Japanese shipbuilders.

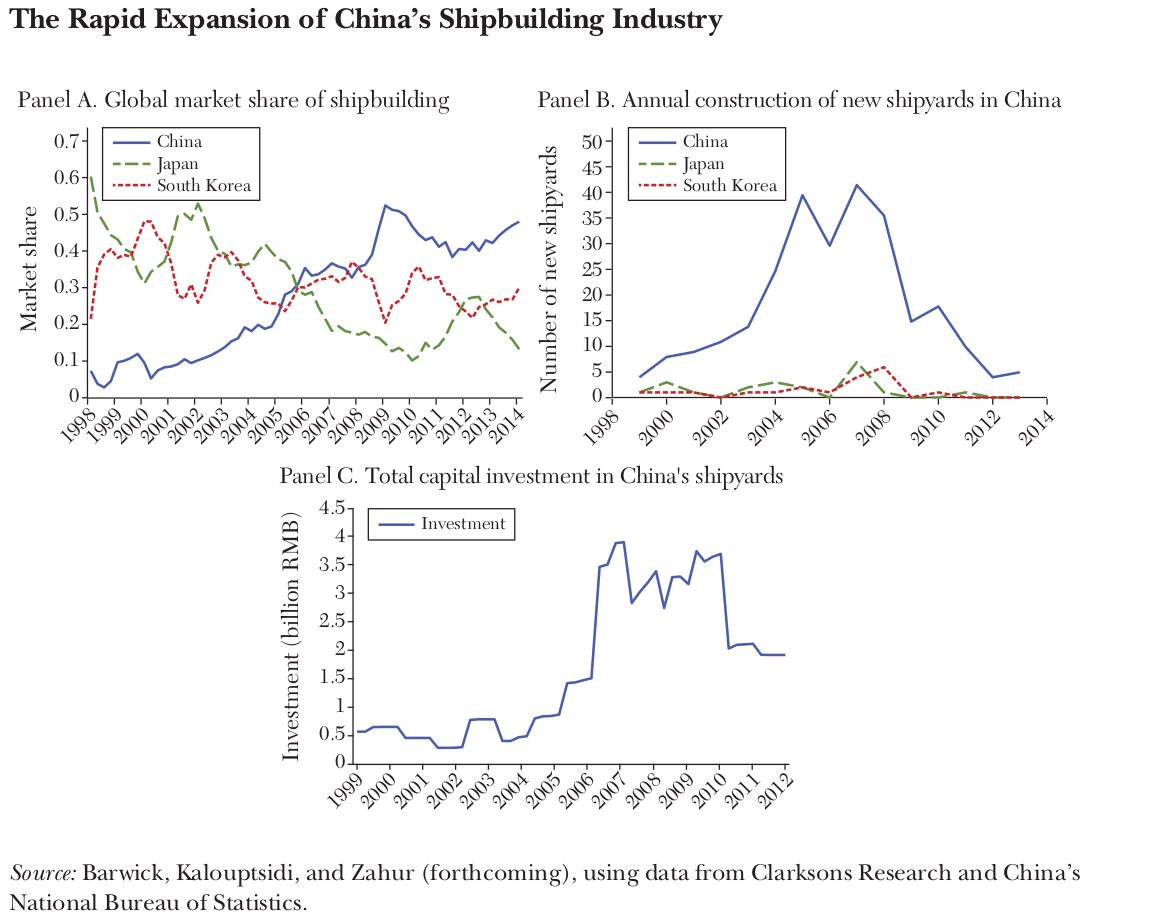

China entered the scene in the early 2000s and by 2009, it had overtaken both Japan and South Korea with a market share of 53% from 10% in 2000. China recognized the need to build its shipbuilding capabilities as early as 2003 and in its 11th 5-year plan of 2006-2010, it labelled shipbuilding a "strategic industry."

China's focus on shipping didn't just stop with building ships but would become much more expansive but we'll get to that later. So, one way of thinking about industrial policy is as tilting the deck to favor a certain industry to force or engineer certain outcomes. Which leads to the natural question: does industrial policy work?

Measuring Success

As soon as you ask the questions, one must grapple with the how in the measurement of success. In the case of Chinese shipbuilding the authors measure success mostly in financial terms. Here are the broad numbers:

- Between 2006 and 2023, the total subsidies to the shipbuilding industry were $91 billion

- Of this, $63 billion was in the form of entry subsidies. This mostly involves providing land mostly for free

- $23 billion was in the form of production subsidies like subsidized steel, export credits, and preferential financing for ship buyers

- $5 billion was in the form of investment subsidies like low-interest loans, tax incentives etc

Note: Chinese numbers are highly unreliable and at best give you a directional sense of X. The same applies to shipbuilding. In most cases there are large implicit and hidden subsidies that are difficult to capture due to the paucity of data and shoddy reporting by local governments, provinces, etc.

Was the Policy Successful?

Well, the shipbuilding industrial policy made China the world's largest shipbuilder. It boosted China's domestic investment in shipbuilding by 140%, doubled the entry rate of shipbuilding firms, and raised China's market share by 40%. China's supply of shipping capacity also led to lower shipping prices which was a benefit for ship buyers.

But if you look at this in terms of return on investment, then it's mostly a failure. The return was minus 82%.

Finally and most importantly, although China's shipbuilding subsidies were highly effective at achieving output growth and market share expansion, we find that they were largely unsuccessful in terms of welfare measures. The program generated modest gains in domestic producers' profit and domestic consumer surplus. In the long run, the gross return rate of the adopted policy mix, as measured by the increase in lifetime profits of domestic firms divided by total subsidies, is only 18 percent, meaning that for every $1 the government spends, it gets back 18 cents in profitability. In other words, the net return when incorporating the cost to the government was a negative 82 percent, with entry subsidies explaining a lion's share of the negative return.

Why the Negative Return?

Well, the bulk of the subsidy was in the form of entry subsidies i.e., free land. Coastal land was provided for free or low prices. So $70 billion of the total $90 billion was just entry subsidies. This lowered the profitability hurdle for shipbuilding companies and also lowered the entry barriers.

Paradoxically, the lower entry barriers led to the entry of low productivity firms which exacerbated the volatility of the already volatile shipping industry and increased the excess capacity further depressing the rate of return.

Overall, I think we do find large support for the industry. Our main finding is that they get very little in terms of pure economic returns. I think we have a negative return of 80 percent. So you give $1, you get back $0.20. Because the entry subsidies are such a big chunk of it, this negative return is driven by these entry subsidies. In retrospect, this is a very intuitive finding, because what's happening is if you give a subsidy to a firm to enter, this means you're lowering the threshold that a firm needs to overcome in order to enter. So a firm thinks, how much money do I need to make to enter? How much am I going to pay? And there's going to be some firms that are marginal, that are expecting to make just below the cost. And all of a sudden you're lowering the cost, which means that it becomes profitable for these firms to enter. But of course, if these are the firms that have the lowest expected profitability, they are the least productive firms. So all of a sudden when you lower entry costs, you allow the least productive firms to enter. And because an important feature of this industry is its high volatility—demand spikes and demand busts—you have all these unproductive firms who are exacerbating excess capacity. They're bringing prices down. They're making volatility worse. This was a big reason behind this low return that we're finding.

So in short, China's shipbuilding industrial policy accomplished China's probable objective of dominating the shipbuilding industry. Its gains came at the expense of South Korea and Japan even though Chinese shipyards were much less efficient. But if you measure this in terms of the return on investment, then the answer is no.

I'd argue that China doesn't really care much about return on investment.

Why am I saying that? I have another post on this tomorrow.

Pranav—India’s 1991 reforms

I’ve begun reading a paper by Douglas Irwin on India’s 1991 reforms journey.

There are many myths around those reforms that try to kill how important they’re perceived to be. There’s a strand of the political right that can’t seem to stomach the fact that a Congress government could actually improve our country. There’s a strand of the political left that willingly blinds itself to the fact that this country has improved. And then there are political cynics who just don’t believe the Indian government is capable of any progress — and thus lays the credit at the IMF’s doorstep.

These idiotic constituencies muffle the importance of independent India’s most critical juncture. This sowing of doubts doesn’t benefit anyone very much — what’s done is, thankfully, done — but it ruins our confidence in pulling off such miracles again. It’s important to correct the record.

Over the next few days, I’m going to use this space as a rough note book, reading important papers that go deeper into this idea. Starting with Douglas Irwin’s recent paper on the 1991 reforms, which I will be taking notes from, with heavy commentary of my own.

How bad were things, really?

- India was practically a closed, isolationist economy. 95% of the market for manufactured goods, and 100% of the consumer goods market was controlled by domestic producers.

- Some people might see that as a good thing — after all, what’s to dislike about Indian businesses having so much importance? Well, here’s what: that importance could only exist because the average Indian had to bankroll those businesses.

- There were quantitative restrictions on imports — that is, there was a quota of how much you could import something. And quotas always create shortages. In this world, if your neighbour bought a foreign car, you could be banned for doing so — because India’s quota was exhausted. This would, of course, lead to corruption and smuggling.

- On top of that, there were tariffs of as high as 300%. In a sense, as long as your efficiency wasn’t so shit that your competitors could ship something for less than a quarter your price, the Indian government would protect you from them.

Why were we being so boneheaded?

- One, we wanted to boost Indian industry. Of course, this hadn’t worked at all, and we barely had any industry to speak of. But, to the babus of the day, this was simply a reason to extend protectionism for even longer.

- Two, we had kept the Rupee artificially high, and that turned us into a basketcase. Our imports were unnecessarily cheap, preventing Indian businesses from being able to keep up. And our exports were unnecessarily expensive, preventing us from entering foreign markets.

- Think of how moronic this is. We created a situation that was skewed against Indian businesses. And to off-set that, we banned foreign businesses too, and sent the bill to Indian consumers. In all, you had a country that was hostile to business as a whole and hostile to consumers.

- How did we get ourselves into this terrible, low-level equilibrium? I suspect it’s because we feared change more than we loved progress, and so, our only achievement was to keep change at bay.

How dramatic was the shift from there?

- Exports tripled in importance to our economy in a mere 10-15 years, going from 5% to 15% of our GDP between the late 1980s and the early 2000s.

- A single nine-year long period of acceleration, from 1993 to 2002, added a trillion dollars of national income. By the year 2000, national income was up by a quarter.

- Our progress in poverty eradication went up by 5-6x.

- Here’s what’s even more interesting. While the overall package of reforms took 3 years to implement, most of that work was done in ten hours. In ten mere hours, we went from a basketcase to an emerging market.

While it wasn’t Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 Third Plenum, this is still one of the most remarkable changes in fate the world has seen. Irwin argues that this was all possible not because of the World Bank or IMF, not because of nameless corporate lobbies, but because of a humble bunch of economists at the right place at the right time.

We’re going to dig through the best of Irwin’s paper in the coming days.

Kashish—Love for personal finance

Personal finance has a special place in my heart. I may write a lot about complex economics and finance topics for work, but I get the most satisfaction from writing personal finance pieces. In these pieces, the author often repeats the same old principles and stories again and again in a new and novel way that nobody has thought of. I find them breezy and cool to read, yet they add very little value. So I stopped reading those. But every now and then, I pick my favourite authors like Nick Maggiulli, Morgan Housel, or Vishal Khandelwal.

I will attempt to write something similar here, but I might fail miserably. Here I go.

While making your personal financial plan and deciding on your investments, the most important question remains “asset allocation.” In fact, there was a study done in 1986 which concluded that asset allocation decisions accounted for about 90% of the variability in a portfolio's returns over time.

It is not about trying to time the market with your line-drawing wizardry on charts. It is not about finding the next multi-bagger in a cesspool of junk-grade penny stocks. It is not about gambling on that “insider” tip, thinking you’re two steps ahead of hedge funds.

It's plain and simple asset allocation.

But there are two ways to approach it: (i) how you should do it or (ii) how you think you can do it.

The first approach is very simple and my personal favourite, because I think it is based on first principles. Every investment you make has a goal in mind—something you want to achieve at a future time, with a certain amount in mind. Since these numbers are about the future, we can never be completely certain, but it still helps. Once we have the goal in mind, it becomes somewhat clear what our asset allocation should look like. For simplicity, if we only had two assets—equities and debt—we could allocate more to equity for long-term goals (anything five years or more away) and to debt for shorter-term goals due sooner. Just doing this would solve most of your investment problems.

Another approach is more academic but less practical (in my opinion). Here you engage in the exercise of risk-profiling, which I consider useless because it fails to do the one thing it is supposed to do: map your risk. I have never seen anyone who, when the market is down 30%, decides not to invest more money—a common question in most risk-profiling questionnaires. By design, most risk-profiling results end up being “aggressive,” so they fail to be truly accurate.

Even if that weren’t the case, it still ends up being of little use. Let’s say you are labeled “conservative,” meaning a higher exposure to fixed-income products like debt rather than equity. Yet your financial goals might require your portfolio to earn 10% annually for the next 10 years. We all know that’s not possible with debt, unless you go for those crypto FDs that my fellow finfluencers are fond of (wink wink). So you are left with either lowering your goals or going against your risk profile, which is again an inefficient way of doing financial planning.

This is why I said two ways: (i) how you should do it or (ii) how you think you can do it. In the latter, you are under the illusion of how much “risk” you can assume, and you invest accordingly. In the former, you do exactly what needs to be done to achieve your goals—no ifs, no buts.

I know I could have done a better job explaining this in more depth, but here’s my unedited and quick version.

Also, this is not something I learned today, but something I have been internalizing ever since I got into personal finance. The trigger for this was a meeting where we ended up talking about it, and I thought I would pen down my thoughts so I can sound smart in front of my boss, who was also part of the same meeting. Please give me a good appraisal, Bhu1 🙏

Tharun—Just like your boss, Trump wants employees back in office

Just like your boss, Trump wants all federal employees back in office. The White House issued an order on Monday, 20th Jan, instructing millions of federal employees to return and start working from the office all 5 days of the week. He also sent an email to federal employees, giving them the chance to resign by Feb 6, simply by responding to the email with one word "resign". And if they resigned, severance benefit will be given till the end of September.

Of course, similar to how you are dissatisfied with your boss's decision of asking you to come work from office, various unions supporting federal and government workers are also unhappy with Trump's decision. Randy Erwin, national president of the National Federation of Federal Employees (NFFE), said in a statement last week: "Unions representing public workers have blasted Schedule F. The policy is among a slew of executive orders designed to intimidate and attack nonpartisan civil servants under the guise of increasing efficiency. However, these orders will do the exact opposite."

Now what is Schedule F? Well, Trump just made it easier to fire federal employees through Schedule F. As mentioned in this article: "From meat inspectors to border patrol officers, many Americans who work for the federal government could soon see their jobs reclassified into at-will positions, meaning they can be dismissed for nearly any reason."

"We can stop the efforts to fire hundreds of thousands of experienced, hard-working Americans who have dedicated their careers to serving their country and prevent these career civil servants from being replaced with unqualified political flunkies loyal to the president, but not the law or Constitution," AFGE National President Everett Kelley said in a statement.

Is Trump taking a note off of Elon's playbook, where Elon fired 80% of the workforce when he took over X(Twitter)? I don't know, but we all know how that turned out for Musk.

Sources:

- NPR - Federal Workers Have Until Feb 6 to Resign with Benefits Through September

- CBS News - Trump Orders All Federal Workers Back to Office 5 Days a Week

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.