Bhuvan

Ever since the 2008 global financial crisis, the advanced economies had gotten used to low and steady inflation. In fact, they did their best to generate inflation by using all sorts of unconventional monetary policy tools like quantitative easing, but inflation remained stubbornly low.

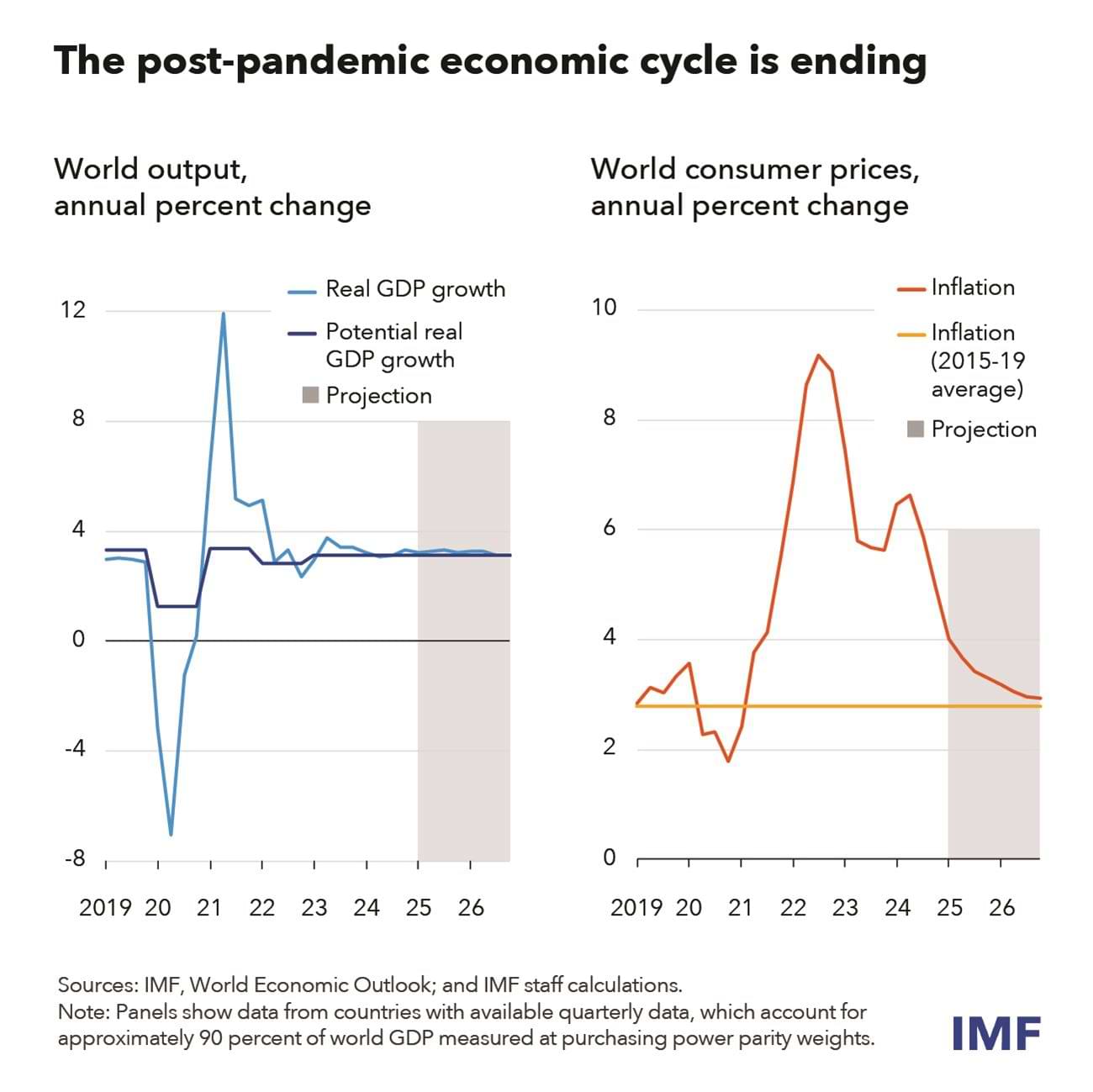

That changed with the pandemic and we saw a historic spike in inflation across both the advanced and developing world to levels we hadn't seen since the 1970s. The intensity varied but the trend was pretty much the same everywhere. Even Japan of all places finally started seeing some inflation.

Since 2021, there's been a raging debate among economists about what caused the inflation:

- Was it driven by demand, fueled by stimulus checks and pent-up spending?

- Or by supply shocks, including pandemic-related supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine?

- Perhaps it was both, exacerbated by large-scale money printing?

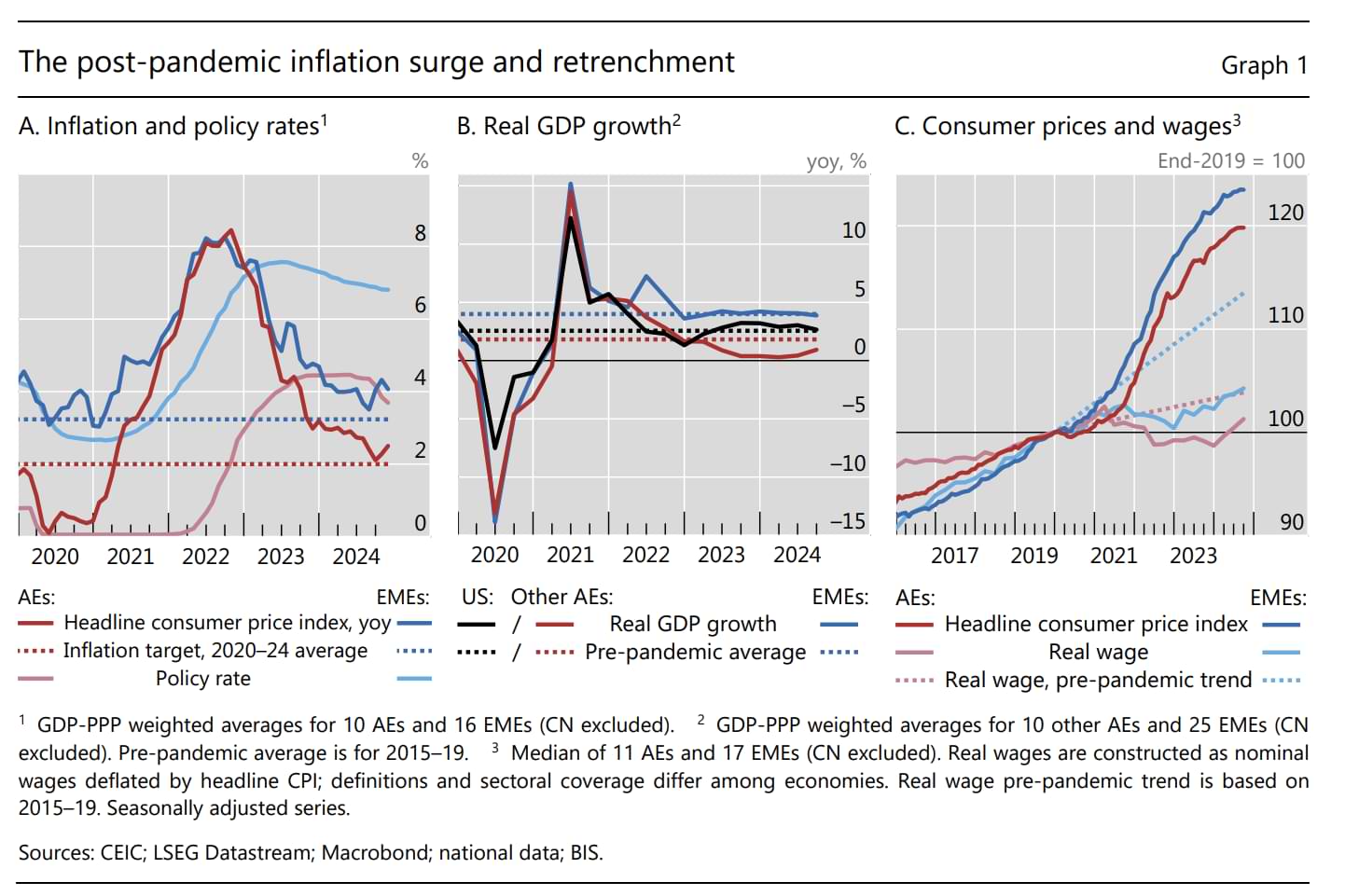

Since then, inflation has steadily fallen across much of the advanced and major economies, barring a few exceptions. Although it hasn't fallen back to the pre-pandemic levels, it's fallen significantly from the pandemic peak.

There have been several interesting papers that have contributed to this literature including this recent one by Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard and also this one in the RBI bulletin. This month, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) published a bulletin congratulating the central banks, and stating that their decisive action in raising rates dramatically helped anchor inflation expectations, leading to the fall in inflation:

Second, and probably a more decisive factor, monetary policy played a key role in anchoring inflation expectations, preventing the pandemic- and war-related massive price increases from triggering broader second-round effects. Medium- and long-term inflation expectations remained remarkably stable during the inflation surge (Graph 2.B). Short-term inflation expectations rose, but much less than actual inflation rates, and have now returned close to pre-pandemic levels.

Monetary policy contributed to the anchoring of inflation expectations via three channels. First and foremost, it operated through the credibility of the monetary policy frameworks, built up during the prolonged period of low and stable inflation preceding the pandemic.2 Second, clear communication from central banks underscored their commitment to bring inflation back under control.3 Third, words were backed up by actions through policy rate hikes, proving central banks’ resolve to curb inflation. Indeed, since the beginning of the monetary policy tightening in AEs in mid-2022, interest rate hikes significantly reduced both short- and medium-term inflation expectations (Graph 2.C). Specifically, econometric estimates indicate that over this period a 1 percentage point increase in two-year bond yields, driven by monetary policy, lowered inflation expectations by approximately 0.5 percentage points for the one-year horizon and 0.25 percentage points for the five-year horizon.

This begs the question: Did central bank actions bring down inflation or did they get lucky?

Dario Perkins, Managing Director at TS Lombard has an interesting counterpoint—central banks just got lucky!

So how did we end up in this position? The authorities – and their cheerleaders in academia and in thinktanks – want us to believe that recent developments are testimony to the importance of independent central banks. It was their “credibility” that delivered lower inflation without a recession. Their decisive actions kept the expectations fairies on side, which anchored inflation at low levels. Without the aggressive policy response and the “credibility dividend” central banks had built up over decades of monetary success, we could easily have slipped back into the wage-price spirals of the 1970s. At least, that is their story, and they are sticking to it: “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. In reality, of course, there are massive holes in that thesis. For a start, I don’t think we were ever in danger of “repeating the 1970s”. The world today looks structurally very different, and 40 years of neoliberalism cannot be reversed with a one-off fiscal stimulus, however large. Inflation is not just about money; it is about power. And workers today were never going to have enough power to generate a persistent wage-price spiral. But it is not just the fake 1970s counterfactual that is problematic with the “aren’t we lucky to have credible central banks” thesis. It is important to acknowledge that the authorities are taking credit for some disinflationary dynamics they were never in control of.

To redress the balance and provide a counterargument to the “official” narrative (not to mention the inevitable flurry of CB research papers), I can think of at least three ways the authorities have been lucky or are taking credit for things that would have happened anyway:

I agree. In fact, an earlier BIS bulletin from 2023 more or less alludes to the fact:

We argue that, absent the somewhat delayed but vigorous increases in policy interest rates since 2022, inflation would have subsided more slowly in 2023.

The hidden subtext of this debate is how effective and potent are central banks? I'm in the camp that central banks and monetary policy do matter, but their abilities and effectiveness has been vastly overstated to the point that there's unwarranted mythology around them.

Pranav

I don’t really understand data. I don’t know how to process it. That makes me a bit of a second-hand story-teller. I don’t have original conclusions; I need people to tell me what the numbers mean.

That’s probably why I’m a terrible investor too.

But I tried experimenting with it anyway. I tried staring at some graphs on electricity consumption from China, courtesy threads by David Fishman and Glenn. My only agenda was to ask “why?” whenever I saw something.

Here’s what they say:

- One, China’s energy consumption, overall, went up by 6.8%. A sizable increase. But why is that? A lot of it has to do with more air-conditioning being used. But what does that mean? Is China’s economy picking up? Are people just forced to use air conditioning because of a terrible heat wave?

- Two, over the second half of 2024, the electricity consumed by its industrial sector hasn’t gone up very much, year-on-year. What does this mean? Is Chinese industry seeing tepid growth? Or is it just a base effect thing, because late 2023 was wonderful for Chinese industry?

- Three, its services sector seems to have expanded, because electricity consumption is growing over a high base. But what does the ‘services sector’s’ power consumption actually mean? The sector seems to include everything from hospitals to artificial intelligence to shopping malls. Surely, everything can’t be growing together, right? What’s the real story, then?

Forgive me. I have absolutely no insight to offer. Just questions.

But these are questions I’ll come back to, the next time I come across something about China.

Why China? I think China’s a very easy country to hate, especially if you’re Indian. And because of that, you’re always willing to believe anything negative you hear about the country. Off late, there’s been plenty of negative news around China, and I think that’s made people a little too comfortable with the idea that it’s down and out. Should one trust this story?

I think the smart thing to do, here, is to invert the question and ask: why might it be wrong? What might it be overlooking?

That’s what I’m trying to do.

There’s also a fun little tidbit about the increase in China’s power consumption because of EVs — 27 TWh — is more than the entire power consumption of Nigeria.

China’s vehicle electrification story, from what I can tell, is a modern marvel. Some day, I’ll go down the rabbithole of exactly how they cracked it.

Tharun

I was reading Just Keep Buying by Nick Maggiulli hoping to increase my savings and build wealth to finally buy my dream house and a Ferrari. With my current trajectory and the lifestyle inflation creep, it looks like I'll never reach that goal. But to make sure you reach your goals and don't end up on the same path, here's what I've learned from reading half the book.

- To build wealth, it doesn't matter when you buy stocks - whether it's a bull market or a bear market - as long as you keep buying.

- Buy investments like you buy food - regularly and consistently.

- Some interesting stats: The bottom 20% of income earners saved 1% of their income, the top 20% saved 20%, the top 5% saved 37%, and the top 1% saved 51%.

- Savings go up as income increases. This is why common rules like "save 20% by X age", "6 months of salary" etc. is bullshit. Personal finance is well - personal.

- The fear of running out of money is greater than actually running out of money.

- The reason why poor people stay poor isn't because of poor financial habits. It's because of the lack of initial wealth. Studies show that when poor people are given assets that lift them out of poverty, they have better chances of escaping it. And poor people stay poor because they don't have enough money to get access to better education and amenities, which keeps them stuck in the poverty trap.

- Cutting your expenses to increase savings is a sure-shot way to live a miserable life.

- A significant portion of millionaires are well-educated and are corporate employees. The notion that education is bullshit, is peddled by people selling online courses.

- On average, it takes 32 years to become a millionaire if you follow the traditional career path. Take this stat with a bucket of salt and don't blame me if you die broke.

- Use the 2X rule to spend money guilt-free. For example, if you want to buy a guitar that costs 40k to advance your music career and you think you're splurging, invest 40k into the markets to not feel guilty. I bought a 40k guitar and didn't invest, and now I feel guilty.

- Spend money on things that give you long-term fulfillment. The guitar purchase is that for me.

Krishna

I was listening to this podcast by Freakonomics—Does Advertising Actually Work?

There were a bunch of interesting insights and facts that completely blew my mind.

Now, I know ads are a big business for Meta and Google, but I was still shocked when I heard this:

More than 80 percent of Google’s revenue comes from advertising; more than 98 percent of Facebook’s revenue comes from advertising.

That’s nuts.

Anna Tuchman, a marketing professor, found that doubling TV advertising only results in about a 1% increase in sales, suggesting that advertising is 15 to 20 times less effective than commonly believed. Then, do you remember seeing those irritating banner ads on websites? Here's an interesting stat about it:

People often forget that when banner ads were first launched on the internet, their click-through rate was like 50 percent—completely mind-bending, right? And it’s just continued to fall and fall and fall. And now, it’s like 0.01 to 0.03 percent.

This particular line stayed with me.

They were discussing whether ads work or not with a marketing executive in the company, and to their surprise, the executive said it worked. That’s when they quoted this:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.