Pranav—More questions on DeepSeek

In yesterday's post, I was trying to get to the questions one should ask if one really wants to understand DeepSeek's significance. I had a few questions — including some that I think were rather spot on. But they still seemed half-arsed. I was just skimming the surface.

A smarter way of doing this, I suppose, is trying to understand what goes into AI, and then reasoning out what has and hasn't happened.

After a couple of hours of breaking my head, here's what I understand:

Behind the scenes are all the physical inputs that go into AI. That includes everything from hardware, to energy, to infrastructure. This is one place where America has an out-and-out advantage, of a sort that Chinese competitors cannot — as far as I know — even hope to match. The future of the AI industry, then, is one of the degree to which DeepSeek (or other Chinese peers) can side-step these disadvantages.

At the heart of a model is its storehouse of knowledge — its weights. It is what the model understands about how different words and concepts connect together.

- At the first instance, these are put together over an extensive process of training — where your AI consumes a civilisation's worth of data. This is possibly the most expensive part of training AI. It's what requires $100 billion GPU super-clusters. Here, I think Anthropic and OpenAI retain an advantage.

- You need access to training data in the first place, and while you can scrape a lot of it from the internet, that need not be enough. I believe the Chinese have a distinct disadvantage here. Their competitors are all backed by the giant data hoarders of the last technological generation. And the fact that they're wealthier means that they can negotiate for better reserves of paid data.

- Pure data, surely, isn't enough. Another place where models can differ is how good they are at creating accurate weights by processing their training data. Frankly, I don't have much of an insight here.

- All of this gets you to a frontier model. Once you do have a frontier model, though, you can do something clever — you can make this model a "teacher", and have "student" models ask it thousands of questions. Over this process, the student model gets almost as good as the teacher, without having to go through a ridiculously expensive training process. This is called "distillation". My hypothesis is that DeepSeek did precisely this, piggy-backing off the effort of companies like OpenAI and Anthropic. And so, despite monumental disadvantages, they could close the gap with their competitors.

Equally important is the AI architecture, or the way in which the AI is arranged. That determines how the whole thing comes together. An AI system is, in a way, made of layers of software, and rules on how information goes from layer to layer.

- The range of architectures available to you is limited by the kind of hardware you can access. This should have been where the Americans had an obvious advantage, because their chips can do much more. But that's where the script was just flipped.

- DeepSeek managed incredible breakthroughs with the architecture. They made their models far more efficient, requiring a fraction of the memory space, and a fraction of the processing power.

Allied: there's also the actual codebase that makes this whole thing run. I don't really know the first thing about how the competition lines up here. Ask the techie nearest to you, I guess.

I think this gives you some basis to ask deeper questions:

1. Sizing up the American training advantage

If training original, undistilled models is where the American moat lies, how far does that moat take you? How much further can you get to by simply processing higher volumes of data? What are the incremental benefits that you can get to by spending more compute, or refining your training methods?

One possibility is that this doesn't create too much of an advantage — that there are diminishing returns from training. If that's the case, the war for AI resources may already be on its last legs, and an entity like DeepSeek is primed to break the competition open.

The other, of course, is that there's still room to unlock a lot of performance. In that case, we'll probably see a constant cycle of American firms making leaps first, and others catching up with them over a couple of years.

2. How much intelligence is enough intelligence?

Our current state-of-the-art AIs can beat the average PhD student at the subject they specialise in. I'm not sure how much more intelligence we need — although, of course, that's because I've never had access to such intelligence. Is there a point at which any additional smartness stops impressing us? And if so, how close are we?

There's a version of the world where more intelligence, at least in the foreseeable future, is an incredible thing. Every model shocks and surprises us for years, and AI's abilities advance to a point we haven't imagined so far. In this universe, the Americans retain a palpable advantage for the foreseeable future, and at best, DeepSeek remains a scrappy competitor that's somehow punching above its weight.

There's another — where we get all the intelligence we'll ever need soon enough, and anything beyond that is just overkill. The investments stop looking sensible, and the competition shifts. Maybe we start looking for better applications, or for AI with more bells-and-whistles, but the intelligence game has already played itself out. Then, the real differentiator will be the kind of innovation DeepSeek did — and the whole "let's get more GPUs and see what happens" approach starts looking like some quaint techno-barbarism.

3. Will the Americans save their model weights?

If DeepSeek distilled itself from OpenAI / Anthropic's models, and there remains more scope for companies to improve their model weights, you'd expect them to do something to keep their models to themselves, and stop others from piggy-backing off their work. They might hide their frontier models, or rate-limit access to them, or figure out some other hack that keeps competitors away. What does this mean for the industry? Really, this could go anywhere — from AI espionage wars, to OpenAI becoming a B2B company that trains other people's models for them, using their super-smart 25th generation AI.

4. Will the Americans adopt DeepSeek's innovations?

DeepSeek made amazing progress, and then told everyone about it. To what extent do the others try and replicate its success? What does this do to the future of the industry?

We now know that the American "more is better" approach was flawed, and architectural innovation can produce profound improvements. Do the Americans care? Do we quickly see others adopt MLA and MOE and everything else DeepSeek does, and the industry becomes more competitive as a whole — and if so, how hard will it be? Or do they just go "How cute, the GPU-poors want to play too!" before buying another hundred thousand H100 GPUs?

So DeepSeek probably used $5 million in their final training run. But what happens when you use the same techniques, but this time, use the full power of American compute?

What happens when the mass of geniuses in American AI turn their attention towards other cost-saving architectural innovations? Do we now expect a series of improvements — not in intelligence, but in efficiency.

5. Bonus: What does DeepSeek really want?

Right now, they look like a really cool bunch of people — hobbyists that want to push the intellectual frontier. But if there's anything the last 30-odd years should teach you, it's that you never trust a techie that claims they have a golden heart. We know that technology allows you to earn money in weird, non-intuitive ways. Are we looking at yet another evil big-tech strategy in its infancy?

These aren't my only questions, by far. There are more — from how the economics of cheap open weighted models might work, to what happens in a world where your phone can natively run an AI model. I'm too brain-fried to explore them. Maybe some other day.

Krishna—Failing to understand DeepSeek

Since we are trying to write a piece on DeepSeek for The Daily Brief, I have been trying to read and understand what innovative thing has it done. I’m a little scared to admit that I’m more confused after reading up on it than before I knew anything about it. During my research, this one term Mixture of Experts(MoE) kept popping up so let me try and explain what it means. Correct me if I am wrong.

MoE is like having a team of specialists (experts) where only the right expert gets called for a job, instead of making everyone work on everything. This saves energy and gets the job done faster.

DeepSeek R1 has made the team manager super smart, so it picks the right expert almost instantly and uses less power. It can handle way bigger teams i.e. models without wasting time or money. Traditional models like OpenAI’s o1 make the whole team of experts work on every problem, even if it’s unnecessary. This is simpler but wastes a lot of energy and slows things down as the team (model) grows bigger

Bhuvan—Let's Talk About Trump

Given that most of us here (only Pranav) have been obsessed with AI and DeepSeek, I figured I'd write about something different today but equally entertaining—Trump! Michael Cembalest, the Chairman of Market and Investment Strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset Management, writes an insightful monthly letter called Eye On The Market, and it always makes for an insightful and entertaining read.

Blame it on content overload, but I hadn't read one in a while. So, I read the most recent letter, and it was fun, to say the least. The current letter looks at the spate of executive orders signed by Trump, covering everything from immigration, energy, taxation, and tariffs. Reading it reminded me of the famous soliloquy in Shakespeare's Macbeth:

And then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Here's how the Trump section of the letter starts:

Trump 2.0 is a hodgepodge of distinctly American political strains: the bare-knuckled nationalism and anti-elitism of Andrew Jackson, the tariff-loving protectionism of William McKinley, the small-government/pro-business policies of Calvin Coolidge, the unforgiving enemies lists and vendettas of Richard Nixon, the deportation policies of Dwight Eisenhower, the manifest destiny of James Polk, and the isolationism of 1914-era Woodrow Wilson (yes, there are apparent contradictions in Trump’s agenda). America First policies create risks for investors since their supply-side benefits collide with their inflationary tendencies; there’s not a lot of room for error at a time of elevated US equity multiples. It looks like it will be a volatile year based on changes so far in the 10-year Treasury, but there’s not enough negative information at this time to change strategy in portfolios positioned for continued US growth and outperformance, particularly given a more benign tariff rollout. On the next few pages, we look at the eruption of executive orders yesterday with a focus on the ones with the largest impact on markets and the US economy.

This reminded me of something utterly brilliant that the eminent historian Stephen Kotkin said in a recent interview:

I get impatient when I read or hear people say about Trump, “That’s not who we are.” Because who’s the “we?” I don’t mean when Trump is called a racist and people insist “we” are not racists. Or when Trump is called a misogynist and people say “we” are better than that. I just mean that Trump is quintessentially American.

Trump is not an alien who landed from some other planet. This is not somebody who got implanted in power by Russian special operations, obviously. This is somebody that the American people voted for who reflects something deep and abiding about American culture. Think of all the worlds that he has inhabited and that lifted him up. Pro wrestling. Reality TV. Casinos and gambling, which are no longer just in Las Vegas or Atlantic City, but everywhere, embedded in daily life. Celebrity culture. Social media. All of that looks to me like America. And yes, so does fraud, and brazen lying, and the P. T. Barnum, carnival barker stuff. But there is an audience, and not a small one, for where Trump came from and who he is.

I think this is profoundly insightful.

Back to Cembalest's letter, here's the TLDR:

- Trump's proposal to end birthright citizenship will end up in the Supreme Court, and it may not agree with Trump's move.

- Trump's plan to resurrect drill baby drill 2.0 also seems like a nothingburger, and his plans to pause the disbursal of grant funds for EV infrastructure projects are meh at best. For one, his legal authority to do so is unclear, and another issue is that most of the districts receiving funding are Republican districts. Oh irony, thou art the most cruel!

- Even otherwise, I was always skeptical of Trump's ability to kickstart an oil revolution. For one, the biggest factor that determines investments of oil companies is price; politics comes much later. If crude prices are high, whether Trump wants it or not, oil companies will drill. So this is not even theater; it's noise.

- On Trump and Elon's DOGE, Cembalest points out that US Federal employment as a share of US employment is the lowest in 85 years. The largest employers in the US government are the Defense Department, Postal Service, and Veterans Affairs. The agencies that Elon and Trump hate the most—the Environmental Protection Agency, Securities and Exchange Commission, and Department of Labor—account for less than 1% of Federal employment. So, what DOGE will do is unclear.

- On tariffs, here's a quote: "As a reminder, most macroeconomists who study tariffs believe that they would reduce US manufacturing employment. If they’re right, the impact could well be felt in red states more than in blue ones (8 of the top ten import/GDP states are red)."

I'd recommend reading the full letter.

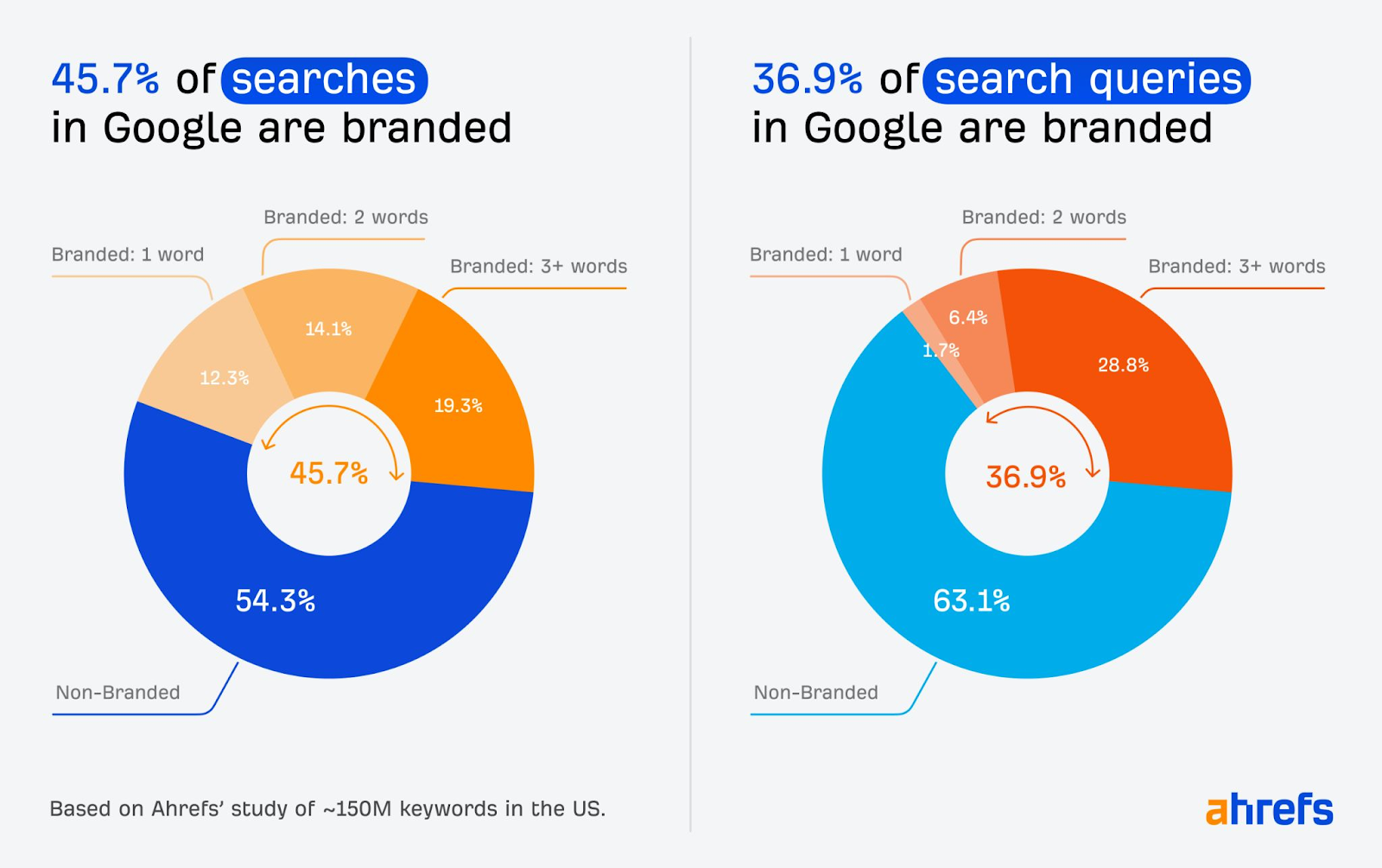

Anurag—50% of Google searches are branded

I recently came across a very surprising stat that I couldn’t believe at first glance—almost 50% of all Google searches today are branded!

This means one in every two Google searches contains the name of a brand. This obviously opens up a lot of marketing opportunities, but more importantly, also lures Google into becoming almost like a graveyard of advertisements.

Today, there are ads that crowd the top of the search page, and in many cases, these ads look almost identical to real results, too.

Also, everything you see before you scroll for the first time on the search result page today tends to be paid content rather than the quick, accurate answers Google used to take pride in.

This shift has made it harder to find good information and, in many situations, it even feels like Google is just useless for organic results while it is super useful as a tool for paid links. Sometimes, even scam sites can slip through the cracks—all as long as they pay money.

Also, given that there’s such a high volume of brand searches, SEO tricks have crept in and have led to a flood of spammy, poorly researched articles that rank highly simply because they hit the right keywords or cram in affiliate links. So, today, searching for the “best” of anything usually leads us to a big list of mediocre & sponsored products.

So, at the end of the day, it currently looks like Google’s biggest incentive is to just keep minting money from ads rather than focusing on the fresh, reliable content we need. It may have slowly become exactly what it once set out to solve.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.