Bhuvan—Why did manufacturing decline in advanced economies?

Donald Trump, our favorite American president has been on a holy crusade to fix all the ills that plague the shining city upon a hill that is America. Like an expert doctor, Trump has diagnosed all the correct problems i.e., fentanyl deaths, deindustrialization, unchecked immigration, massive trade deficits and unsustainable debt. But like a failed medical student who was on psychedelics, he's chosen the wrong cure—tariffs.

One of the biggest justifications that Trump has given for tariffs is the loss of well-paying manufacturing jobs in the United States. Trump blames this on China. Is he right?

Not really.

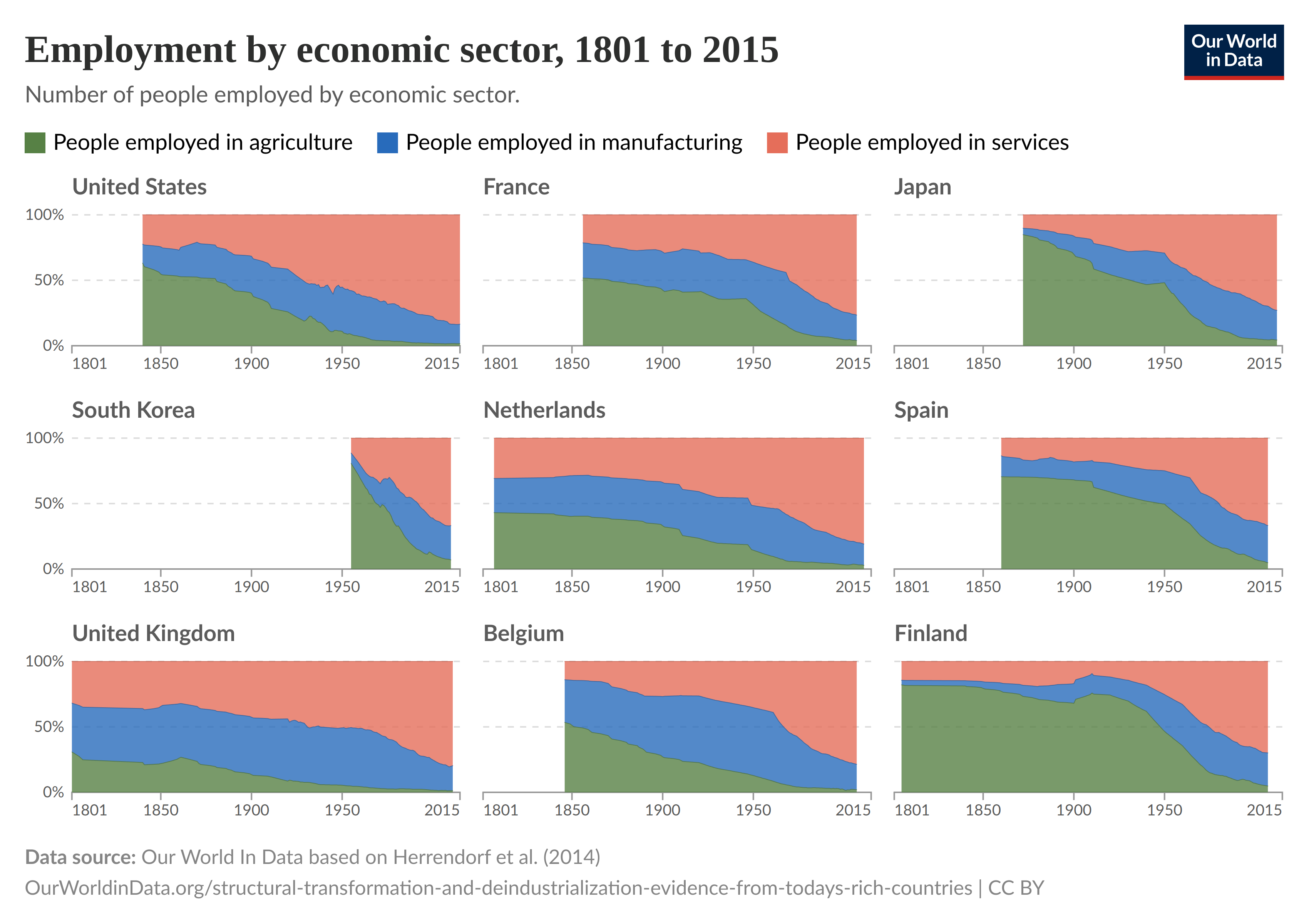

China has become the go-to bogeyman for pretty much the entire American political establishment both on the left and the right. The answer to the question of why manufacturing jobs declined in advanced economies is not simply "China stole them." Yes, China was a factor but the impact of China has been vastly overstated. Employment by economic sector, 1801 to 2015

Regardless of what you think about China, the country has become a catch-all scapegoat for all the ills affecting the West, particularly the United States. The anti-China sentiment varies across parts of Europe, but in the United States, there is vehement and bipartisan agreement that China is the reason why the United States is in its problematic position. This narrative is pushed by people on both the left and right.

But whenever you see monocausal reasoning or narratives about why complex phenomena happen, you should be suspicious. Attributing the entirety of U.S. manufacturing decline to China is not just misleading—it's outright wrong.

The Real Causes of Manufacturing Decline

What's particularly problematic about blaming China for the decline of U.S. manufacturing and associated blue-collar jobs is that this decline is a pronounced trend in most other advanced countries like Japan, the United Kingdom, and other parts of Europe. Even Germany, which is a manufacturing superpower, has seen its share of manufacturing employment decline.

If you look at the manufacturing share of employment for advanced countries, the decline starts somewhere around the 1960s and 1970s—well before the WTO, well before China's ascension to the World Trade Organization, well before "hyperglobalization," and well before the era of unrestricted free trade.

So what's really happening?

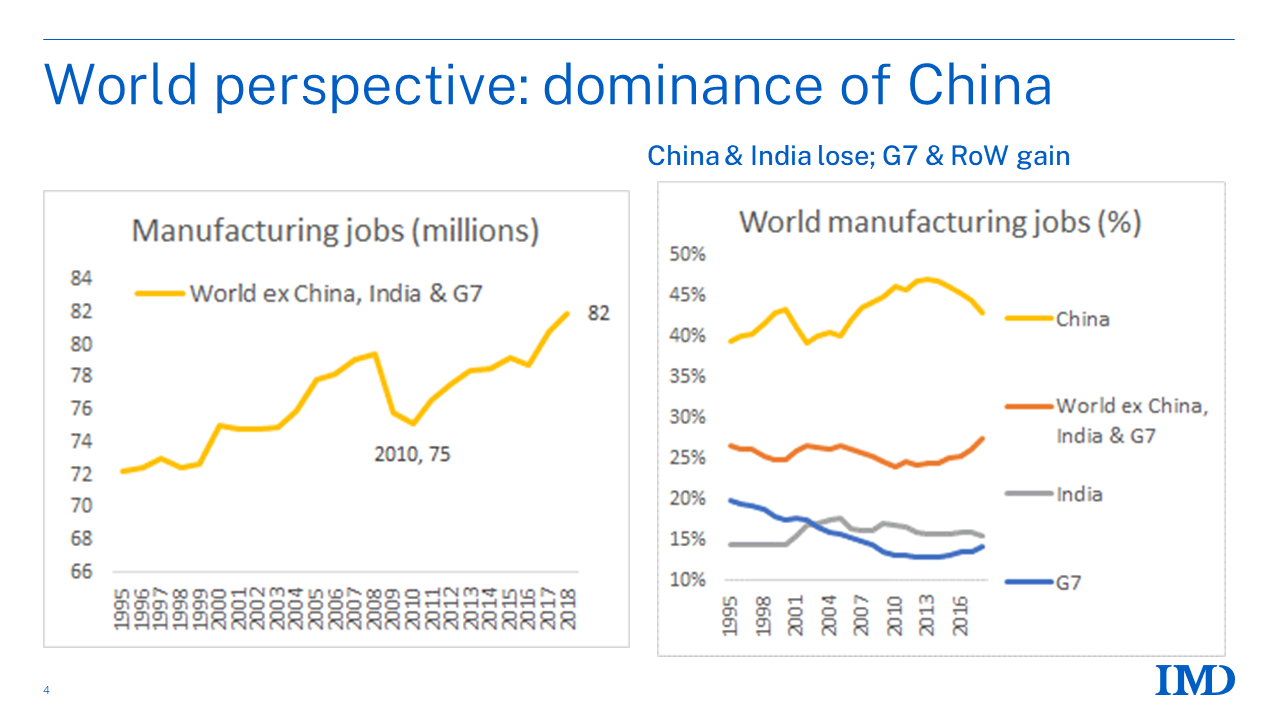

Importantly, China itself has lost 20 million manufacturing jobs between 2013 and 2018 according to Richard Baldwin. So attributing everything to China falls apart right there. It's also not the case that manufacturing simply went to other developing countries, as many advanced economies have lost manufacturing jobs. So why?

Nope! As it turns out, China lost 22.5 million manufacturing jobs from 2013 to 2018 (the last year in the database). Of course, things are never as simple as they seem, but it is astonishing, at least to me, that the worldwide job loss of 23 million is almost identical to China's (see charts below).

The Main Factors Behind Manufacturing Job Loss

Increasing Productivity: More work is being done per employee than at any point in history.

Automation and Technology: Thanks to advanced robotics and mechanical equipment, owners of capital can extract more output while keeping employee numbers constant or even reducing them.

Shifting Consumer Preferences: As income rises, consumers demand more services like healthcare, education, financial services, and leisure. This means an economy naturally evolves to cater to these desires for higher-end services. Consumers in wealthy countries also tend to consume proportionally fewer manufactured goods because there's only so much they need, and their preferences change. This pattern has been well-established in research.

This isn't to say China isn't partially responsible. Globalization enabled the shifting of manufacturing to countries with low labor costs, especially for labor-intensive manufacturing. This is one of the biggest reasons why China became the manufacturing powerhouse that it is.

But the reasons for the decline of manufacturing are multifaceted. The manufacturing share of employment for pretty much all advanced countries began declining around the 1960s for the United States and later (starting in the 1970s-80s) for other countries, including Germany. And as mentioned earlier, even China's manufacturing employment started declining around 2013—the very country labeled as the "thief" of manufacturing jobs.

The Human Impact and Policy Response

Even though manufacturing's share of employment declined, plenty of employment was created in the service sector—teachers, nurses, etc. Richard Baldwin notes that people who lost their jobs are often misleadingly labeled as the "losers of globalization." I don't prefer that term—I think "people who were left behind" is a much more useful way of describing it.

If you compare what's happening in the United States versus other countries like Canada or Europe, the backlash against trade and globalization has been much stronger in the United States. Why? In other advanced economies, social safety nets helped mitigate some effects of manufacturing job losses. Countries in Europe and Canada have universal healthcare, paid parental leave, paid vacation days, free or cheap university education, paid apprenticeships, social housing, robust pension systems, and unemployment benefits.

Social security benefits in the United States, compared to its advanced country peers, are very meager. It's also something of an anathema, as Baldwin points out, in the United States for the government to get involved and provide these benefits. A "rugged individualism" and very strong libertarian streak prevails among much of the American population, with a general distrust toward "big government" providing benefits or assistance.

Governments could have done much more to mitigate the adverse effects of globalization—something as simple as opening free trade gradually instead of unleashing it all at once like a broken dam. But that train has passed.

While people who lost manufacturing jobs in Europe aren't necessarily happy, they're less resentful than their American counterparts. Still, there are commonalities in both regions, as evidenced by the rise of right-wing politics in advanced nations.

The Future of Manufacturing Jobs

The bottom line, as Baldwin and economist Dani Rodrik have pointed out, is that it's folly to think these manufacturing jobs will ever fully return. Some manufacturing jobs might come back, or maybe that's always been the goal. But making grand promises about relocating all the "lost" manufacturing jobs isn't realistic.

Furthermore, tariffs are not a panacea. Perhaps tariffs used in conjunction with other policies—like industrial policy, research and development spending, and tax incentives—can actually help to some extent. After all, if you look at history, advanced countries like the United States and United Kingdom grew their national industries behind high tariff walls, as Rodrik has pointed out.

But the counterfactual is that there have been plenty of countries with high tariff walls that have gone nowhere. So tariffs alone don't explain everything. Tariffs, when paired with other policies that protect domestic industries while simultaneously encouraging them to invest in their workforce and in technology—creating an environment where there's investment in education, healthcare, and R&D, and growth in people's skills—can enable protected industries to reach "escape velocity."

You can see this in China. China is not really an avatar of free trade. The government is heavily involved in picking winners and losers and in capital allocation decisions. Arguably, this has worked because they've achieved dominance in a wide swath of manufacturing. They first started with low-wage and basic manufacturing jobs and are now graduating up the value chain. China is now at par or has surpassed the West in terms of many manufacturing capabilities—perhaps most notably in solar, wind, electric vehicles, battery technology, nuclear technology (especially small modular reactors), and even in high-end domains like chips, where they're not really that far behind the West.

Advanced countries, especially the United States, really lost the plot in terms of making sure they provided a safety net for people left behind by globalization. Now they're trying to correct it by using tariffs as a catch-all solution—a one-size-fits-all approach to fix problems they should have addressed differently. But that's not going to work. Tariffs are one tool, but the way Donald Trump is wielding them is absolutely the wrong approach.

That's it for today. If you liked this, give us a shout by tagging us on Twitter.